By Robin Powell, The Evidence-Based Investor*

Special to Financial Independence Hub

* Republished from the Just Word Blog from Robin Powell, the U.K.-based editor of The Evidence-Based investor and consultant to investors, planners & advisors

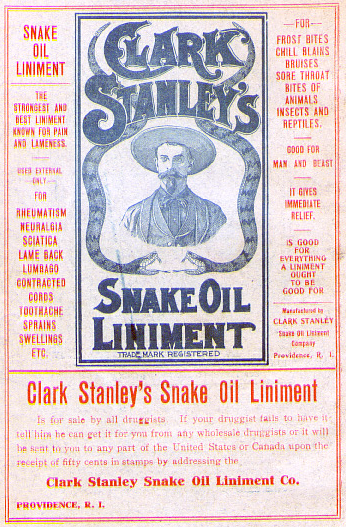

Much as we like to think of ourselves as savvy consumers, we are actually very susceptible to PR and advertising. This is particularly true when it comes to investing.

Big banks like TD, RBC and Scotiabank, asset managers like Sun Life and Manulife, and online trading and investing platforms like Questrade and Wealthsimple, spend vast sums promoting their products and services. The more they spend, the more customers they attract.

Why, then, are people so receptive to financial marketing and so easily persuaded by it? In most cases it’s a lack of understanding. The financial markets are complex, and we’re bombarded with suggestions as to how to invest our money. In a world saturated with information, consumers rely on simple marketing messages to help them make decisions. They also derive comfort and security from large financial brands they’re already familiar with.

Big does not mean Best

The problem for investors is that the firms whose products are most often featured in the media are usually not the best ones to buy. The brands you’re most likely to see sponsoring hockey teams or film festivals, for example, or plastered across billboards in airports or train stations, are often just the sorts of companies you should avoid giving your business to. Why? Because the interests of consumers and big financial brands are often misaligned.

Financial firms are very clever at making it look as though their primary motivation is to help the likes of you and me to achieve better outcomes. But the bottom line is that they’re businesses, and their number one priority is to generate profits. To put it bluntly, these companies want our money. The more money we invest with them, and the more trading we do, the bigger the profits they make.

Financial education is extremely valuable. Educated investors almost invariably enjoy better outcomes. The danger, though, is that, all too often, we think we’re being educated when in fact we’re being sold to.

How Big Brands mislead us

There are all sorts of ways in which big financial brands mislead us. Here are five main ones.

1.) Emotional Appeal

Ideally, investors would act at all times in a calm and rational manner. We would only make decisions after carefully considering the available information and weighing up the options. But human beings are emotional animals, and financial marketers understand this better than anyone. This is why they deliberately appeal to emotions like fear and greed, and the fear of missing out, or FOMO, which, in a sense, is a combination of the two.

2.) Cognitive Biases

As well as their emotions, investors have to contend with a range of cognitive, or behavioural, biases that all of us are prone to. These include confirmation bias (our tendency to seek out information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs), herd behaviour (our instinct to copy what those around us are doing) and recency bias (our tendency to attach more weight than we should to recent events). Financial marketers know just the right buttons to press to exploit these built-in biases.

3.) Expert Endorsements

In his book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, the American psychologist Robert Cialdini writes about the importance of what he calls social proof. When we feel uncertain, he explains, we tend to look to others for answers as to how we should think and act. Closely related to this is the principle of authority, or the idea that people follow the lead of credible experts. So, for example, if someone recommends a certain product or strategy in the media, we’re inclined to take notice, even though that person may be heavily biased or not an expert at all.

4.) Scarcity and Urgency

Another way in which financial marketing leads consumers astray is that it generates a false sense of urgency. So, for instance, we might read about a particular investment “opportunity” — perhaps a hot stock or fund — in the weekend newspapers and feel impelled to buy it first thing on Monday morning. This is a very foolish way to invest. Of course, that stock or fund may well rise in value, but its price could just as easily fall. Regardless, investors are much better off taking a long-term view. It is very rarely, if ever, the case that you need to make an investment decision straight away.

5.) Financial Jargon

The final reason why the industry spin machine causes more harm than good is that it often contains financial jargon. At best, jargon confuses investors and over-complicates the investment process; at worst, it can be used to cloud and deliberately mislead. It can exploit people’s lack of financial literacy and give a false impression of trustworthiness and expertise. But the principles underpinning sensible investing are really quite simple, and consumers should place their trust instead in firms that simplify investing and explain how it works in clear, concise language.

Who can be Trusted?

You may be wondering, “If I can’t trust financial companies to tell me what’s best for me as an investor, who can I trust?”

Well, the good news is, there are firms that are more trustworthy than others. There are also organizations such as FAIR Canada and the Canadian Securities Administrators that help to point investors in the right direction.

Some financial publications are fairly reliable; others less so. Remember: media outlets have their own conflicts of interest. For a start, many rely on banks and asset managers for advertising revenue. Journalists also need a steady stream of “juicy stories,” which explains why there are more articles about active fund managers and the latest products and investment trends than about boring, passive low-cost ETFs.

One journalist I particularly admire is Rob Carrick at the Globe and Mail, who certainly isn’t afraid to ask big financial brands awkward questions. Earlier this year, for example, he showed how Wealthsimple, despite being the dominant player in Canada’s robo-advice sector, has produced substantially inferior returns compared to its rivals, including Justwealth. Wealthsimple’s popular growth portfolio had a five-year average annual total return of 7 per cent after fees up to the end of May 2024. The comparable Global High Growth Portfolio from Justwealth delivered 9.1 per cent.

Ultimately, the best way to protect yourself is to have an adviser who genuinely acts in your best interests. This should be someone with a thorough understanding of evidence-based investing and the benefits of using low-cost, passively managed ETFs as opposed to expensive active mutual funds.

For me, this is one of the ways in which Justwealth has an edge over other investment solutions. Once you’ve opened an account, you’re assigned your own personal portfolio manager, who is independent of financial institutions, and who is there to manage your investments, not to sell you products.

Remember: the sooner you start investing the better. It should only take 15 or 20 minutes to get yourself up and running with a Justwealth account. So what are you waiting for? There’s no better time than now to begin your investment journey.