Come gather ’round people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You’ll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin’

And you better start swimmin’

Or you’ll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin’

- Bob Dylan © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

In this month’s commentary, I will discuss both how and why the environment going forward will differ markedly from the one to which investors have grown accustomed. Importantly, I will explain the repercussions of this shift and the related implications for investment portfolios.

The Rear View Mirror: Where we’ve been

After being appointed Fed Chairman in 1979, Paul Volcker embarked on a vicious campaign to break the back of inflation, raising rates as high as 20%. His steely resolve ushered in a prolonged era of low inflation, declining rates, and the favourable investment environment that prevailed over the next four decades.

Importantly, there have been other forces at work that abetted this disinflationary, ultra-low-rate backdrop. In particular, the influence of China’s rapid industrialization and growth cannot be underestimated. Specifically, the integration of hundreds of millions of participants into the global pool of labour represents a colossally positive supply side shock that served to keep inflation at previously unthinkably well-tamed levels in the face of record low rates.

It’s all about Rates

The long-term effects of low inflation and declining rates on asset prices cannot be understated. According to Buffett:

“Interest rates power everything in the economic universe. They are like gravity in valuations. If interest rates are nothing, values can be almost infinite. If interest rates are extremely high, that’s a huge gravitational pull on values.”

On the earnings front, low rates make it easier for consumers to borrow money for purchases, thereby increasing companies’ sales volumes and revenues. They also enhance companies’ profitability by lowering their cost of capital and making it easier for them to invest in facilities, equipment, and inventory. Lastly, higher asset prices create a virtuous cycle: they cause a wealth effect where people feel richer and more willing to spend, thereby further spurring company profits and even higher asset prices.

Declining rates also exert a huge influence on valuations. The fair value of a company can be determined by calculating the present value of its future cash flows. As such, lower rates result in higher multiples, from elevated P/E ratios on stocks to higher multiples on operating income from real estate assets, etc.

The effects of the one-two punch of higher earnings and higher valuations unleashed by decades of falling rates cannot be overestimated. Stocks had an incredible four decade run, with the S&P 500 Index rising from a low of 102 in August 1982 to 4,796 by the beginning of 2022, producing a compound annual return of 10.3%. For private equity and other levered strategies, the macroeconomic backdrop has been particularly hospitable, resulting in windfall profits.

From Good to Great: The Special Case of Long-Duration Growth Assets

While low inflation and rates have been favourable for asset prices generally, they have provided rocket fuel for long-duration growth assets.

The anticipated future profits of growth stocks dwarf their current earnings. As such, investors in these companies must wait longer to receive future cash flows than those who purchase value stocks, whose profits are not nearly as back-end loaded.

All else being equal, growth companies become more attractive relative to value stocks when rates are low because the opportunity cost of not having capital parked in safe assets such as cash or high-quality bonds is low. Conversely, growth companies become less enticing vs. value stocks in higher rate regimes.

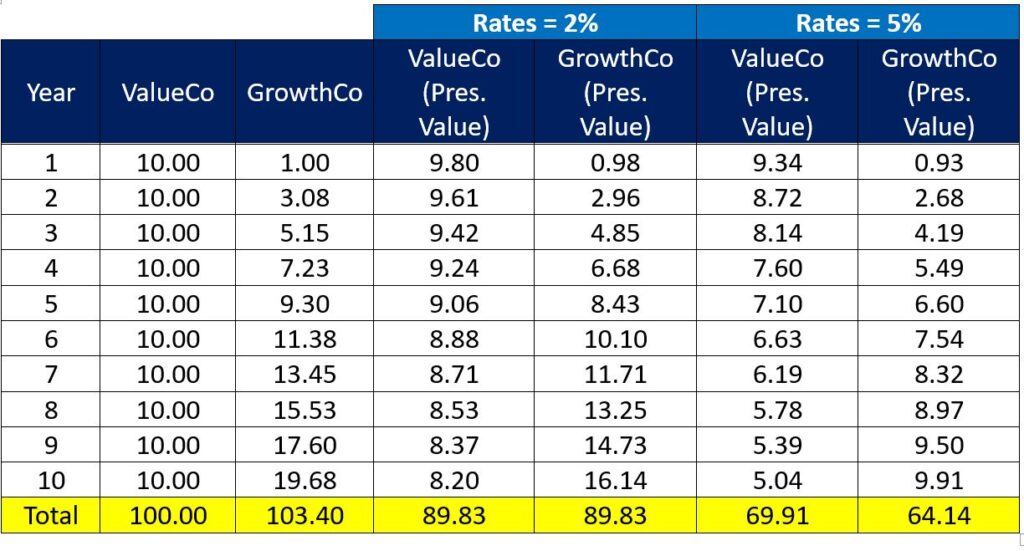

Example: The Effect of Higher Interest Rates on Value vs. Growth Companies

The earnings of the value company are the same every year. In contrast, those of the growth company are smaller at first and then increase over time.

- With rates at 2%, the present value of both companies’ earnings over the next 10 years is identical at $89.83.

- With rates at 5%, the present value of the value company’s earnings decreases to $69.91 while those of the growth company declines to $64.14.

- With no change in the earnings of either company, an increase in rates from 2% to 5% causes the present value of the value company’s earnings to exceed that of its growth counterpart by 9%.

Losing an Illusion makes you Wiser than Finding a Truth

There are several features of the global landscape that will make it challenging for inflation to be as well-behaved as it has been in decades past. Rather, there are several reasons to suspect that inflation may normalize in the 3%-4% range and remain there for several years.

- In response to rising geopolitical tensions and protectionism, many companies are investing in reshoring and nearshoring. This will exert upward pressure on costs, or at least stymie the forces that were central to the disinflationary trend of the past several decades.

- The unfolding transition to more sustainable sources of energy has and will continue to stoke increased demand for green metals such as copper and other commodities.

- ESG investing and the dearth of commodities-related capital expenditures over the past several years will constrain supply growth for the foreseeable future. The resulting supply crunch meets demand boom is likely to cause an acute shortage of natural resources, thereby exerting upward pressure on prices and inflation.

- The world’s population has increased by approximately one billion since the global financial crisis. In India, there are roughly one billion people who do not have air conditioning. Roughly the same number of people in China do not have a car. As these countries continue to develop, their changing consumption patterns will stoke demand for natural resources, thereby exerting upward pressure on prices.

- Labour unrest and strikes are on the rise. This trend will further contribute to upward pressure on wages and prices.

A Word about Debt

The U.S. government is amassing debt at an unsustainable rate, with spending up 10% on a year-over-year basis and a deficit running near $2 trillion. Following years of unsustainable debt growth (with no clear end in sight), the U.S. is either near or at the point where there are only four ways out of its debt trap:

- Raise taxes

- Cut spending/entitlements

- Default

- Stealth default (see below)

In today’s environment, options one and two seem unlikely for the simple reason that no party/politician seems to possess the will to enact policies that may be politically unpopular and could pose risks to getting either elected or re-elected. I also have trouble seeing the U.S. defaulting on its obligations. This leaves a stealth default as the most likely possibility. This course of action entails leaving rates below equilibrium (i.e. at overly stimulative levels) for an extended period.

The good news is that this approach will reduce the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio. However, inflating away debt necessarily involves tolerating higher levels of (you guessed it) inflation! This is another reason to fear that inflation will be less well-behaved than what markets have grown used to.

Where I get Confused

Although unlikely, a return to the halcyon days of disinflation and ultra-low rates is nonetheless possible. However, this does not mean that such an outcome would result in growth-stock outperformance, for the simple reason that it is already being reflected in valuations. Investors are suffering from an acute case of recency bias whereby they are extrapolating the benign inflation of decades past.

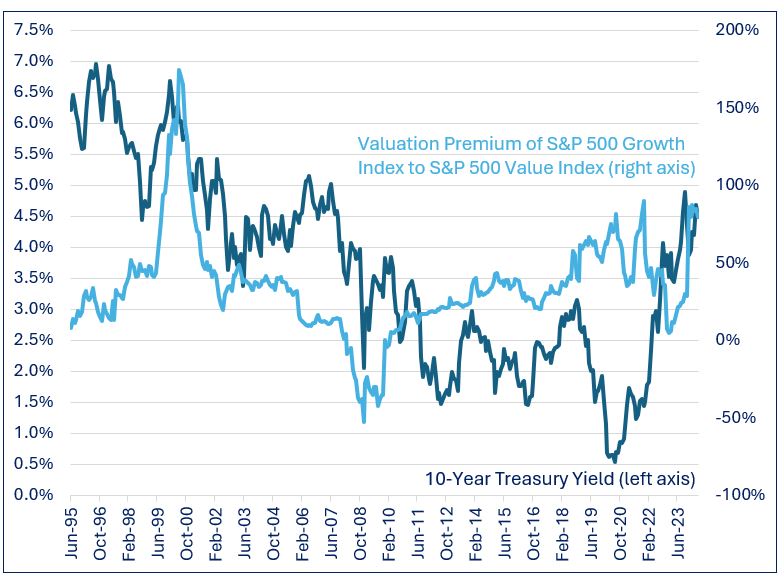

S&P 500 Growth Index & S&P 500 Value Index: Relative Valuation vs. 10-Year Treasury Yield

- The Covid-induced flood of fiscal and monetary stimulus caused a spike in the relative valuation of growth vs. value stocks. As of the end of November 2021, the yield on 10-year Treasuries was 1.4%. At that time, the P/E of the S&P 500 Growth Index was 90% higher than that of the S&P 500 Value Index, which was the highest it has been since the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s/early 2000s.

- By February 2023, runaway inflation coupled with an aggressive Fed hiking campaign drove 10-year yields up to 3.9%. This had a deleterious effect on the relative valuation of growth stocks, which stood only 6% higher than their value counterparts.

- As of the end of May, the 10-year yield of 4.5% was well above its November 2021 level of 1.4%. Strangely, growth stocks have nearly regained their valuation premium, with the PE ratio of the S&P 500 Growth Index sitting 79% higher than that of the S&P 500 Value Index.

What this means for Investors

It is unlikely that we will witness a return to the disinflationary, ultra-low-rate world which in many ways defined markets in recent decades. And yet, the belief lives on longer than the reality. Given the extreme valuation of growth vs. value stocks, this is exactly what is currently being discounted by markets.

This asymmetry presents an opportunity for investors, who would be well-served to tilt their U.S. exposure in favour of value over growth stocks. By the same token, prudent allocators should seriously consider trimming their exposure to the growth-heavy U.S. market and adding exposure to Canada and other non-U.S. countries.

Since its inception nearly six years ago, the Outcome Canadian Equity Income Fund has produced a cumulative return of 62.9%, as compared to 50.3% for the TSX Dividend Aristocrats ETF (symbol CDZ). Putting this outperformance in perspective, according to a report by S&P Global 93.9% of income-focused Canadian equity funds have underperformed the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index over the past five years. Importantly, we have outperformed while exhibiting lower volatility and consistently suffering shallower losses in falling markets.

Postscript

We have recently applied the same algorithmically driven process behind our Canadian equity income fund to large-cap, dividend-paying U.S. equities. We are confident that this new mandate will follow its Canadian predecessor in adding value for our clients.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude).

Noah is frequently featured in the media including a regular column in the Financial Post and appearances on BNN. This blog originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished here with permission.