Darling, I don’t know

Why I go to extremes

Too high or too low

There ain’t no in-betweens

And if I stand or I fall

It’s all or nothing at all

Darling, I don’t know

Why I go to extremes

- I Go to Extremes, by Billy Joel

By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

The stock market crash of 1929, which was followed by the Great Depression, was arguably the best thing to happen to investors in the history of modern markets.

I am in no way suggesting that investors took pleasure in having their life savings largely obliterated, nor am I implying that bear markets are enjoyable. However, the tremendous pain that people experienced left them with a deep distrust of stocks that lasted for decades. It was this wariness that kept valuations in check, thereby paving the way for strong returns.

Both the passage of time and rising markets eventually led investors to relinquish their pessimism. Eventually, acceptance morphed into adulation, the widespread view that stocks harbored no risk, and an “it can only go up” mindset that culminated in the late 1990s tech bubble. This excessive optimism caused valuations to become untethered from reality, with the S&P 500 Index reaching its highest valuation in history and huge market capitalizations being awarded to companies with little or no earnings.

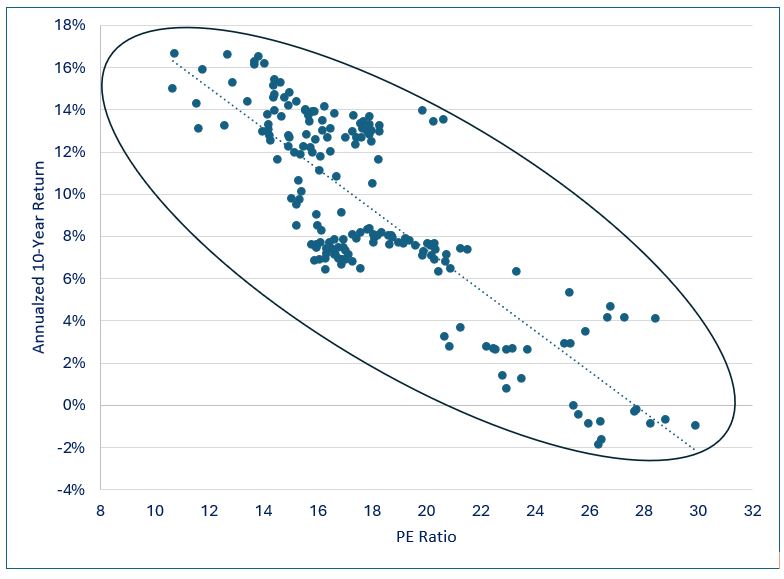

The irrational enthusiasm which created and propelled one of the greatest bubbles in modern history also set the stage for its ultimate demise in the form of a painfully long and deep bear market. Over shorter periods, fear can result in missed opportunities and regret while greed may get rewarded. However, over the long term, starting points of excessive pessimism set the stage for healthy markets while starting points of excessive optimism pave the way for disappointment. This observation is captured in the following graph, which clearly demonstrates that higher starting valuations lead to lower returns, and vice versa.

S&P 500 Index: PE Ratio vs. 10-Year Annualized Returns

This relationship brings to mind the following guiding principles of legendary investor Howard Marks:

- It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay that counts.

- Good investing doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.

- There’s no asset so good that it can’t become overpriced and thus dangerous, and there are few assets that are so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain.

- The riskiest thing in the world is the belief that there’s no risk.

Forget Forecasting: Context is Everything

I know that booms, recessions, bull markets, and bear markets have happened and that they will happen. Where I run into trouble is knowing when they will happen. I am in good company when it comes to this deficiency, as economic forecasting has by and large proven to be an exercise in futility. As famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith stated, “The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable”.

Given that predicting when changes in economic conditions will occur is a fool’s errand, investors should instead concern themselves with how markets will react if they occur. Importantly the same change can have a vastly different effect on markets depending on where valuations stand. Specifically, stock market multiples can be a gauge of the extent to which prices will decline in reaction to an adverse shift in the economic backdrop.

If you are standing right on the precipice of a cliff and a strong gust of wind hits your back, there is a good chance you’re done for. On the other hand, if you are standing a few feet back from the edge, then you will probably avoid the reaper. Similarly, negative surprises result in lower losses when significant risk is discounted in prices, while such shocks can cause far more serious damage when valuations are overly optimistic.

We can do this the Easy Way or the Hard Way

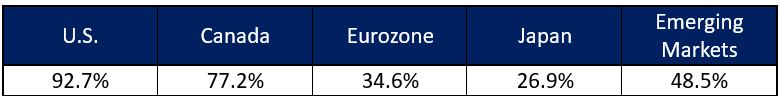

As indicated by the table below, at the end of last quarter the S&P 500’s current PE ratio stood at the high end of its range over the past 25 years. Given its relatively high valuation, it comes as no surprise that the S&P 500 has suffered steeper losses than other equity markets in reaction to increased risk and uncertainty. Relatedly, it is far from shocking that the higher multiple segments of the U.S. market have underperformed their less expensive counterparts, with the Magnificent Seven group of stocks falling by an average of 23%, roughly double the decline in the S&P 500 Index.

Dec. 31, 2024 Equity Market Valuation Percentiles (Past 25 Years)

To be clear, I am not suggesting that current valuations will lead to a bear market in U.S. stocks akin to those of the Great Depression, the global financial crisis, or the dotcom crash. Rather, I am merely stating that the elevated multiple of the S&P 500 Index leaves it more exposed to price declines than non-U.S. stocks.

Historically, when the index’s multiple has been in its current range, annualized returns over the subsequent 10 years have ranged from plus 2% to minus 2%. Although such an outcome is far from enticing, it is not disastrous. However, as the saying goes, “we can do this the easy way or the hard way”. The easy scenario involves a benign reversion to average valuation levels whereby prices remain mostly stagnant for several years as earnings rise. The hard way entails an abrupt multiple compression/bear market.

Lastly (and I am admittedly violating my own principles regarding prognostication here), the lack of any significant valuation “cushion” to mitigate losses in the face of adverse developments seems amiss given the uncertainty unleashed by the new U.S. administration. In other words, it’s unadvisable to stand on the precipice of a cliff even when there is no wind, but doing so when there is lightning in the sky seems especially frivolous.

Adaptability is the Simple Secret of Survival

From a risk perspective, U.S. stocks offer far less of a valuation cushion than their non-U.S. counterparts. Similarly, within the U.S. market, the high-multiple darlings of yesteryear appear to be far more vulnerable to broad-based de-risking episodes than value-oriented companies.

Until recently, the post-GFC environment has been especially supportive of riskier, return on capital-focused portfolios. In contrast, there is a strong likelihood that the current environment, which is likely to persist for the foreseeable future, will favour a more defensive stance that places more emphasis on return of capital. Against this backdrop, investors would be well-served to favour non-U.S. over U.S. equities while tilting their individual holdings within countries towards defensive, lower-volatility sectors and stocks.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds. Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds. Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies.

Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude).

Noah is frequently featured in the media including a regular column in the Financial Post and appearances on BNN. This blog originally appeared in the March 2025 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished here with permission