To shed light on effective wealth-building strategies, we’ve gathered insights from nine experts in the field, including investment specialists, financial advisors, and more.

From the importance of diversifying your portfolio and investing in yourself to the consistent investment in stock indices, these professionals share their top investment opportunities and asset classes that have proven particularly effective in securing financial independence.

- Diversify Your Portfolio and Invest in Yourself

- Prioritize Exchange Traded Funds (EFTs)

- Look into Home Ownership and 401(k) Investments

- Make Systematic Progress Across Asset Classes

- Generate Passive Income with a Niche Website

- Build Wealth through Real Estate

- Focus on Healthcare and Nutraceuticals

- Seek Rental Property Investments

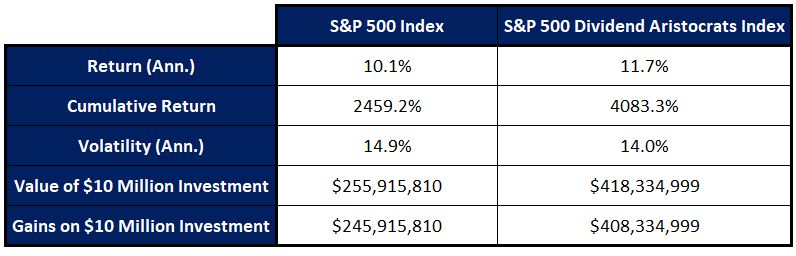

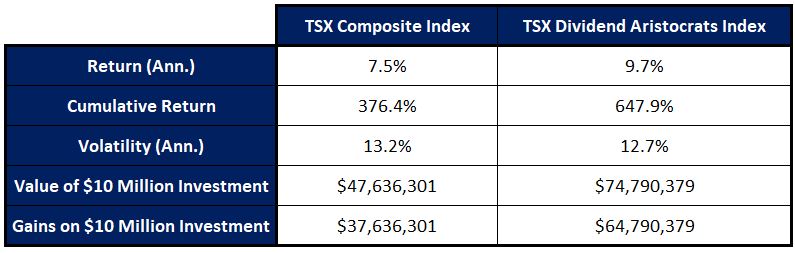

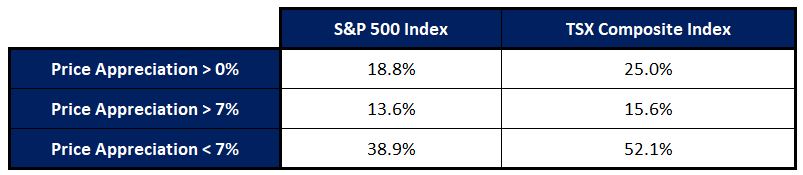

- Be Consistent with Investment in Stock Indices

Diversify your Portfolio and Invest in Yourself

One investment opportunity that has proven particularly effective in building and securing financial independence is a diversified portfolio that includes a mix of equity, bonds, and alternative assets.

This strategy allows for exposure to different asset classes, mitigating risk while aiming for growth. Equities provide the potential for high returns, bonds offer stability and income, and alternative assets such as real estate, commodities, or private equity can add further diversification and potentially enhance returns.

However, it’s essential to emphasize that investing in oneself has been the best investment of all. Personal and professional development, education, and acquiring new skills have consistently yielded substantial returns over time. These investments enhance earning potential, open up new opportunities, and empower individuals to adapt to changing circumstances. — Ahmed Henane, Investment Specialist and Financial Advisor, Ameriprise Financial

Prioritize Exchange Traded Funds (EFTs)

The equity market is the single greatest wealth creator for investors. If someone has 10 years or more as their time horizon for investing, then an equity growth mutual fund or ETF (Exchange Traded Fund) is highly recommended to build wealth.

ETFs are very similar to mutual funds. ETFs typically represent a basket of securities known as pooled investment vehicles and trade on a stock exchange like individual stocks. A growth ETF is a diversified portfolio of stocks that has capital appreciation as its primary goal, with little or no dividends.

One such investment would be the Vanguard Growth ETF (VUG/NYSE Area). This ETF is linked to the MSCI US Prime Market Growth Index, which offers exposure to large-cap companies within the growth sector of the U.S. equity market. Investors with a longer-term horizon ought to consider the importance of growth stocks and the diversification benefits they can add to any well-balanced portfolio. — Scott Krase, Wealth Manager, Connor & Gallagher OneSource

Look into Home Ownership and 401(k) Investments

There isn’t any one asset class or investment opportunity I’d recommend over the other for the general populace. Those types of financial decisions are circumstantial and based on the needs of the client.

Nonetheless, the two ways to “Build Wealth for Dummies” would be to purchase your home and invest in your 401(k). From a behavioral-finance perspective, the automatic contributions to these two vehicles have, more often than not, created better outcomes for clients. — Rush Imhotep, Financial Advisor, Northwestern Mutual Goodwin, Wright

Make Systematic Progress across Asset Classes

A systematic progression across multiple asset classes has been successful in developing wealth and financial freedom. A cash-generating firm provides a stable financial basis for future projects.

Real estate investing offers passive income and property appreciation, boosting financial security. Diversifying the portfolio with equities and other assets follows, harnessing the potential for exponential growth and mitigating risk through a well-balanced mix. However, amidst this multifaceted approach, it is crucial not to overlook the most pivotal investment: oneself.

As Warren Buffett wisely advised, “Be fearful when others are greedy and be greedy only when others are fearful.” Investing in self-improvement, education, and personal development enhances decision-making acumen and emotional resilience, providing the intellectual foundation to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of wealth accumulation. — Galib A. Galib, Principal Investment Analyst

Generate Passive Income with a Niche Website

A few years back, an affiliate website was launched in the personal finance niche. The payoff? Consistent ad revenue and affiliate commissions with minimal oversight, essentially becoming a self-sustaining income stream.

Running a website is not as time-consuming as commonly believed. After the initial setup and content, it just needs occasional updates. Soon enough, it turned into a low-maintenance income source. Continue Reading…