The following is the second excerpt from Create the Retirement You Really Want: And Retire Smarter, Richer and Happier

The following is the second excerpt from Create the Retirement You Really Want: And Retire Smarter, Richer and Happier

By Clay Gillespie

Special the Financial Independence Hub

It was a beautiful May morning when I next saw Rachel and Mike. Rachel was carrying a large gift-wrapped box.

“This is for you,” she said, smiling and handing the box to me.

“Thank you,” I said, pleasantly surprised. “Most of my clients wait until they see how their portfolio performs before expressing their appreciation.”

“Shall we take it back then?”

“No, no! I’ll keep it,” I said, smiling, as I began to slide off the ribbon and remove the wrapping.

I opened the lid, looked inside and grinned with pleasure. “Much appreciated,” I said, looking proudly at a genuine leather soccer ball with my daughter’s name custom-printed on the top panel. “Sarah’s going to love it!”

“We wanted to give you a memento of our first meeting,” Rachel said.

“How very appropriate. Well, I don’t have a soccer ball for you,” I said, putting the ball down. “But hopefully I have an equally useful gift.”

“One that will last a lifetime?” Rachel asked.

“Yes. You might say it’s a gift that keeps on giving,” I said, grinning and handing them each a file folder.

“Our retirement numbers?” Mike asked.

“Yes. These are your illustrations.”

“Will we need to eat cat food?” Mike asked with a smile.

“No.” I laughed. “My goal is to help you maximize your retirement income, not minimize it.”

“And we won’t outlive our money?” Mike asked, more serious now.

“You should have plenty left for your children, unless you live to be Methuselah’s age.”

“Methuselah lived to be 969 years old,” Rachel said. “So I think the odds of that happening to us are slim,” she said pointedly.

“Right. My mistake,” I admitted. “I’ve taken the liberty of including a life expectancy table in your retirement illustration, so you’ll know the odds.”

“The odds of us dying at a certain age? I’m not sure I’m ready to see that!” Mike said uneasily.

“Don’t be such a worrywart, Mike,” Rachel said, chiding him gently. “It’s not as if you’re going to see the exact date and time of your death.” Suddenly, she frowned and looked at me. “Are we?”

“No,” I said smiling. “The actuaries aren’t that good, at least not yet. The life expectancies I’ve included are estimates based on a number of factors including your current age, your diet, exercise frequency, stress, body fat, genetics and the quality of health care.We’ll get to those in a moment. What you’re about to see is a financial illustration. It’s designed to give you an initial picture of your retirement situation for planning purposes. But first, we need to review your finances together so we’re all on the same page. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” they said together.

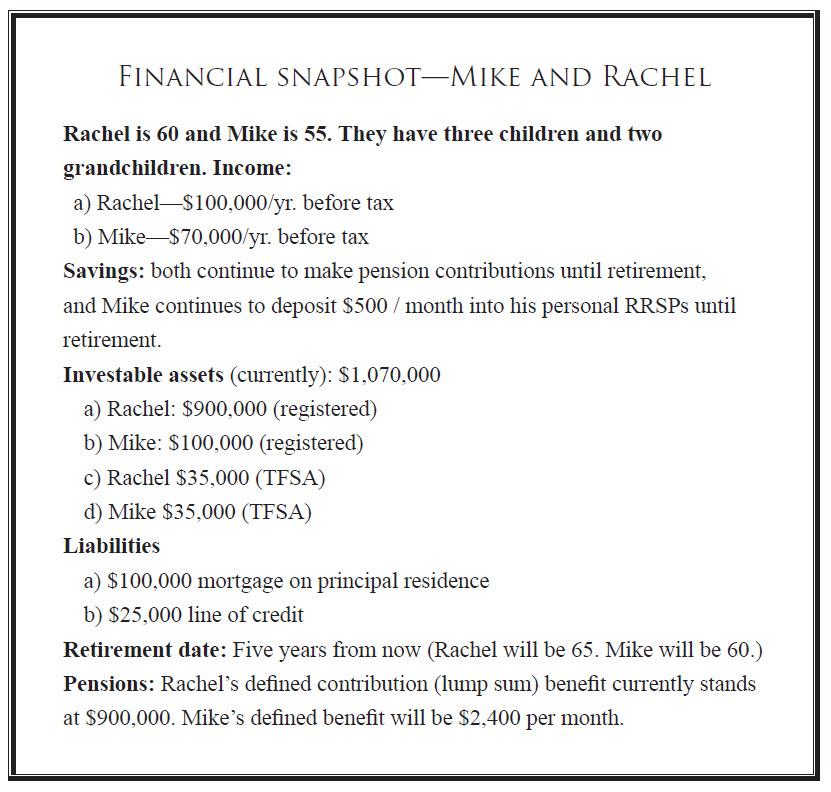

“Good. Here’s a quick snapshot of your current finances. As we go through it, I want you to let me know if anything is amiss.”

This is what they saw:

“As you can see, your gross income is $170,000 per year, while your combined income after tax is approximately $125,000.” “We work hard for our income,” Rachel said defensively.

“I don’t think anyone disputes that. You’re certainly not wealthy or one of the so-called one-percenters. Fortunately, you have pensions. And you’ve been maximizing your RRSP and TFSA contributions. We estimate you’ll have $1.4 million in investable assets when you retire. For that, you are to be congratulated. Now, regarding your pensions.”

I looked over at Mike, “Mike, you have a defined benefit plan which will provide $2,400 a month in income. And Rachel,” I glanced her way, “barring any terrible market shocks, your defined contribution plan will kick in in five years, giving you a lump sum of roughly $1.2 million. Does all this square with your estimates?”

“Yes,” Rachel said. “Has anything changed since we spoke on the phone?”

The Big Question

“No,” Mike said. “Now it’s time for you to answer the Big Question.”

“Which is?”

“What sort of return can we expect to earn on our money?”

“It’s a good question, and a very normal question, but it’s not the most important one to ask when you’re retiring.”

“You know, Clay, I’m kind of getting used to you telling me I’m asking the wrong questions,” Mike replied.

I laughed. “You don’t ask the wrong questions, you ask the questions most retirees ask. But capital preservation, not growth, should be the most important goal for retirees. So, before I can answer your question about return on investment, we need to look at your whole financial picture—especially your retirement income.”

“Isn’t that the Big Question?” Rachel asked. “How much income will we have when we retire?”

“Yes, it is. Good one, Rachel!”

She smirked. Mike gave her a dark look.

“So what’s the answer to the Big Question?” Mike asked, annoyed with both of us.

“Actually there are three answers.” “Three?” said Mike. “Really?”

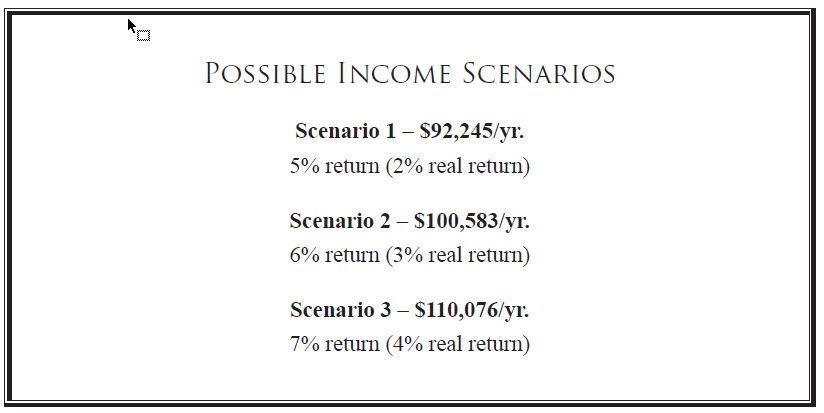

“Yes,” I said, unperturbed. “I’ve put together three income scenarios for you.”

Three Income Scenarios

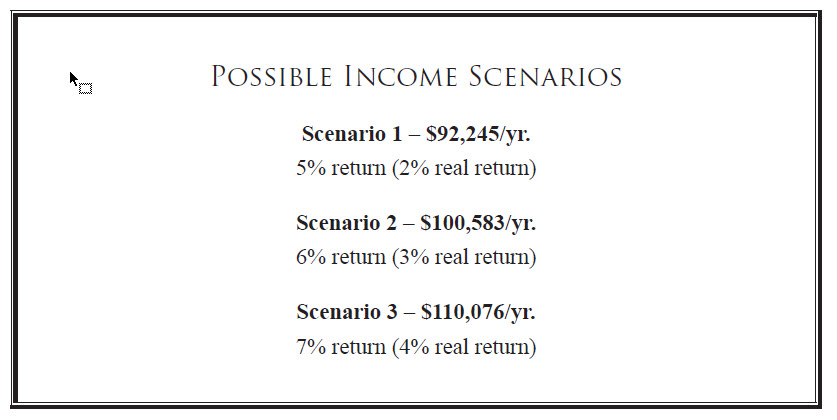

This is what they saw:

“Scenario one gives you $92,245 of spendable income each year. Scenario two gives you $100,583 of income per year. Scenario three gives you $110,076 of income each year.”

“Scenario one gives you $92,245 of spendable income each year. Scenario two gives you $100,583 of income per year. Scenario three gives you $110,076 of income each year.”

Mike’s mood changed. “These numbers are pretty good,” he said, grinning. “I especially like the last one.”

“Yes, these are healthy numbers, but it all comes down to lifestyle,” I said. “I know retirees who have trouble living on five hundred thousand a year. It’s all about matching your lifestyle needs and expectations with your income. Some retirees lead extravagant lifestyles, but many don’t. Our firm surveyed individuals who were within three and seven years of retirement and found that only a quarter expect to have an income of $5,000 a month or greater.”

“We’re five years away from retirement,” said Rachel. “Will these numbers be relevant when we retire?”

“They should, unless you make big changes in your goals or your financial situation. But remember, this is a preliminary plan. We will adjust, as needed, each time we meet. Which I expect will be annually.”

“How did you come up with our income numbers?” Mike asked. “Each of the income scenarios is based on your life expectancy and lifestyle needs, and then parsed according to three different real rates of return.”

“I know what ‘parsed’ means,” said Rachel with a smile. “But I’m not sure I understand what a real return is.”

“When most people think about returns, they think only in nominal terms. They forget inflation. But inflation is very real, and retirees feel the impact more than any other group because they often live on fixed incomes. Real return is the number that people should really focus on.”

“So real return is simply our return after inflation.”

“Correct. Inflation can dramatically cut your purchasing power and limit your lifestyle over time. Let me give you a simple example. Based on the historical average inflation rate, which is 4 per cent, a lifestyle that costs you $50,000 a year today would be more than twice as expensive in 20 years. You’ve heard of the positive power of compounding? Well, inflation has a negative compounding effect.”

“But inflation is far below 4 per cent, isn’t it?” Mike asked.

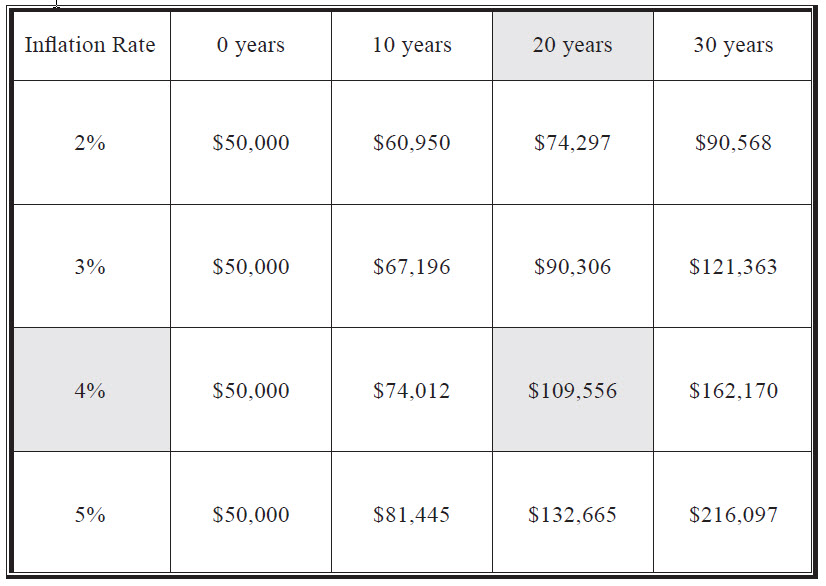

“Right now, yes. But inflation pressures can build slowly and invisibly over time—and then inflation rates can soar. It happened in the 1970s and early 1980s, and it can happen now. To guard against it, we build an adjustment for inflation into your retirement income. Inflation is generally measured by the year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI, in turn, measures how much a basket of commonly purchased goods and services costs, and the CPI tracks the increase in the price of this basket of goods and services over time. This is the inflation rate. There’s a high probability that your retirement could last over 30 years, so it’s important to understand how the inflation rate can affect your ability to maintain your desired lifestyle. Turn the page and you can see some inflation scenarios.”

They flip the page. Their eyes darted to the table below.

The impact of inflation

“Let’s say you lived on a modest income of $50,000 per year during retirement. If the inflation rate were 4 percent (which happens to be the historical long-term average), you would need an income of $109,556 in 20 years’ time to buy the same basket of goods which you could buy today for $50,000.”

“That’s more than double!”

“Even at today’s historically low inflation rate, you must plan for the negative consequences of inflation over time. With 2 per cent inflation your current $50,000 retirement income would need to be over $90,000 to keep its purchasing power if you lived into your nineties.”

“Wow,” Mike said.

“Let’s go back through each of the three income scenarios so you truly understand the differences.” They nodded.

“The first retirement income scenario has you receiving $92,245 per year. This is based on a 2 per cent real return; that is, a 5 per cent nominal return on your assets, less the inflation rate, which we have assumed as 3 per cent. No one knows what inflation will be going forward, but historically 3 per cent puts you in a reasonably safe range. But it really doesn’t matter what inflation is, or even what your nominal rate of return is. All that really matters is your real rate of return.”

“The first retirement income scenario has you receiving $92,245 per year. This is based on a 2 per cent real return; that is, a 5 per cent nominal return on your assets, less the inflation rate, which we have assumed as 3 per cent. No one knows what inflation will be going forward, but historically 3 per cent puts you in a reasonably safe range. But it really doesn’t matter what inflation is, or even what your nominal rate of return is. All that really matters is your real rate of return.”

“That makes sense,” said Rachel. “But what happens to that income over time? For example, scenario one, $92,245. Will it stay the same?” “Not in absolute terms.

Your income is inflation adjusted, so by 2055, for example, it would be 292,000.”

“That’s a whopping big number!” Rachel said.

I chuckled. “It won’t look as big in 2055, I promise you! Not after inflation has eaten away at it. The income numbers include a cushion for emergencies and contingencies that you’ll likely face at one time or another.”

“We’re talking about a 2 per cent real return. That seems a little low,” Mike said pensively. “Frankly, I was expecting more from the markets than that.”

“Remember, these are real returns, not nominal returns.”

“What about scenarios two and three? They give us a higher rate of return.”

“They do. Scenario two gives you a 3 per cent real return and you’d get a 4 per cent real return with scenario three.”

Mike grinned. “Then we’ll take door number three, please.”

“That’s fine,” I said, “just as long as you know that higher return means higher risk.”

“Which one would you choose? Which do you recommend?” Mike asked.

“How much income will you need when you’re retired? That’s what it boils down to.”

“So you’re saying our income needs determine how much risk we’re willing to take on?”

“Broadly speaking, yes.”

“How do you determine the rates of return?”

“We look at the historical relationships between different asset classes. For example, we know that a low-risk five year GIC has generally outperformed the inflation rate by 1 to 2 per cent. We also know that the Canadian stock market, which we define as the S&P/TSX, should, over time, outperform the inflation rate by 6 per cent. If the inflation rate stays at 2 per cent, the best expected average return from the stock market is in the neighborhood of 8 per cent. For a more conservative balanced portfolio, the expected long-term return is about 6 per cent.”

“Are those numbers fixed in stone?”

“Not at all. But they’re good guidelines. It’s also important to keep in mind that this relationship can take at least two market cycles to hold.” “Why do you use 3 per cent inflation in your scenarios if 2 per cent is more common?”

“We simply prefer to err on the side of caution.”

“What if inflation spikes up? What if it goes much higher than 3 per cent?”

“Historically, if the inflation rate rises, your expected market return should also rise over time. For instance, if the banks wish to sell GICs in a high inflation environment, the GICs must carry a higher interest rate or consumers will put their money elsewhere.”

Mike glanced at Rachel. “I don’t mind taking on risk, Rachel. What about you?”

“I don’t want any risk, thank you. I’m going to be retired.”

“You can’t avoid risk altogether,” I said. “Not unless your portfolio is all fixed income and no growth. Then you’ll just be creating another kind of risk— inflation risk—and you’ll be fighting a losing battle. My investment philosophy has always been to minimize risk while allowing for growth. I’m a conservative person by nature, and I believe retirees have to be conservative as well. Keep in mind that for the first time in your lives you’ll be going from wealth accumulation to wealth de-accumulation.”

“Asset depletion, you mean.”

“Your investment assets will be depleted, but your other assets should stay intact.”

“Like the house and stuff? That’s comforting,” Rachel said.

Costs often fall in retirement

“One other comforting fact you might like. Most retirees’ living costs go down in retirement because there’s no need to keep up with the Joneses and generally no mortgage to worry about.”

Mike and Rachel exchanged a quick glance. “We’ve never been worried about the Joneses.”

“Good. And you won’t have RRSP savings to worry about, or EI and CPP premiums to pay. And most of your employment-related costs should disappear. For example, lunches out and transportation and clothing costs, and your dry cleaning bills, these should all decrease— sometimes dramatically. There are a number of risks to retirement, but day-to-day expenses are usually not one of them. You’ll likely be pleasantly surprised at how they fall away.”

“I hate surprises,” said Rachel.

“Rachel even hates surprise birthday parties,” added Mike with a chuckle.

“Especially my own,” Rachel replied.

“Then you’ll really appreciate knowing the risks in advance,” I said. “I tend to point out the risks fairly early, because I know that retirees hate surprises as much as you do. That way, when negative things happen, they don’t worry as much.”

“What are these risks you’re speaking of, exactly?”

The Four Risks

“There are four major ones. We’ve discussed one of them already— inflation. Another major risk is market risk. There’s risk to any stock market investment in the short term, but over the long term the risk is reduced. That said, retirees face a risk that pre-retired investors seldom need to worry about. Some call it sequence of returns risk.”

“Yeah, I’ve heard that term,” Mike said. “Never understood it,” he said, chuckling.

“Here’s how it works. In retirement, you draw down your investment assets, which is the opposite of what you’re doing right now, accumulating assets. When you’re working and accumulating retirement savings over a long period, stock market volatility should not be too much of a concern, provided your portfolio is properly diversified.

“As you know, we’re diversified across different asset classes,” Mike added.

“Yes, I was happy to see that. Good for you, because many investors aren’t. As you might have realized by now, one of the greatest risks in retirement planning is having the stock market drop substantially right before or right after you retire. Unfortunately, proper diversification techniques can’t offset this problem alone. Instead, when you’re generating an income during retirement, it’s important that you don’t withdraw funds from an asset class that is declining in value.”

“Which might happen if we retired during a market crash, right?” Mike asked.

“Yes. If you’re unlucky enough to retire when the stock market is performing poorly, but still need to generate income from your portfolio, then you could deplete your capital at an alarming rate. This could set you back quite a bit, because it could ultimately reduce the chances that your portfolio will be able to grow at the rate you envisioned. And this means you might not be able to generate the spendable income you need throughout your remaining retirement years.”

“What can we do to protect ourselves?” Mike asked.

“First, you have to be prepared for a stock market correction every single day. Let me give you a real life example of the kind of thing that could happen. Between August 1995 and August 2005, the average Canadian Balanced Fund earned 7.4 per cent if you’d invested

$100,000 in a typical Canadian Balanced Fund in August 1995, and started a withdrawal rate of 7 percent, which is $583 each month, your account would have been worth approximately $107,700 in August 2005. So far, so good?”

“Yes. Go on.”

“So based on that scenario, you would assume that you could withdraw 7 percent from a balanced portfolio and still maintain your capital. Right?”

“Right.”

“Now what if you’d invested that same $100,000 in the average Canadian Balanced Fund at a different time? Let’s say, for example, five years later, in August of 2000.”

“That would have been just before the tech crash, wouldn’t it?” “That’s right.”

“Whoa. I think I see where you’re going with this,” said Mike. “Well, I don’t,” said Rachel, miffed. “Please, go on.”

“If you withdrew $583 each month,” I continued, “which is 7 per cent of your portfolio in this scenario, your account would have been worth $75,600 by August 2005, instead of $107,000, as before.”

“That’s a drop of—what—25 per cent!” Mike exclaimed. “Closer to 30 per cent. And remember, that’s after taking out five fewer years of income.”

“My goodness. Why is there such a big difference?” Rachel asked. “In the first scenario, where you retired in August 1995, the market performed very well for the first five years, so a ‘cushion’ was built up in your portfolio. When the negative return years started, the portfolio was able to weather the storm. In the second scenario, where you retired in August 2000, your portfolio would have taken an immediate hit, so there was no chance to build up a cushion.”

“Wow. It’s a little scarier than I thought,” Rachel said.

“Don’t worry, honey,” Mike said, patting her on the shoulder. “I’ll hold your hand when the going gets rough.”

“Don’t patronize me, mister,” she said, pulling away from him. “I’ve seen you when the markets go into a nose dive, and you’re as chicken as the rest of us.”

I couldn’t help but smile. Investing can be a surprisingly emotional business, even for some of the professionals. “The vast majority of investors get seasick when the market drops like a stone,” I said, “like it did in 1987, and 2000, and 2008. Many studies have been done in this area. Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman researched human behavior and emotional biases and found that the more emotional the financial event, the less rational people were in their reactions to the event.”

“What can we do to protect ourselves from market risk?” Mike asked.

“It’s difficult to accurately plan your retirement around the possible performance of the stock market. But how you take out your income is really important. For example, you could consider lowering your initial withdrawal rate of 7 per cent. Some studies suggest that your initial withdrawal rate should be no higher than 4 per cent, but I don’t necessarily agree. I think an initial withdrawal rate of up to 5.5 per cent is sustainable if you have the proper retirement income strategy in place.”

“What kind of strategy?”

“To avoid withdrawing funds from an asset class that is declining in value, I often recommend doing the following: Invest one year’s income in a high-yield savings account that will be used for the first year’s income. Then invest one year’s income in a one-year bond or GIC. Then invest one year’s income in a two-year bond or GIC. The balance of your investments remains in a diversified portfolio based on your personal goals and objectives.”

“How does that help?”

“The high-yield savings account will deplete itself over the first year. If the growth part of your portfolio has grown in value by that point, you take the following year’s income from the growth portion. In other words, you use some of the growth part of the account to replenish the high-yield savings account.”

“What happens if the markets perform poorly and the growth account shrinks in value?”

“Then you use the maturing GIC to replenish the high-yield savings account. And if the GIC isn’t used for income, it gets reinvested for a guaranteed period of two years.”

“So that way we avoid taking income from any part of our portfolio that is declining in value. I get it.”

“Yes. But keep in mind, your portfolio should be aligned with your retirement objectives well before your planned retirement date. Five years before retirement is optimal. At least two to three years’ worth of your desired retirement income should be in a fixed income vehicle that will mature the day you retire. It could be a GIC or a bond; it doesn’t matter, just as long as it matures on your retirement day. That way, you have at least five years to let the market improve before having to take money from your portfolio to generate income.”

“I like that idea,” said Mike.

“You mentioned market drops. Volatility scares me,” said Rachel. “I went through the 2008 financial crisis on pins and needles and sold some stocks we shouldn’t have. I don’t want us to panic and do something stupid when we’re retired.”

“You mean, like pull all our funds out of the market if there’s an even bigger drop than 2008?” Mike asked, with just a hint of sarcasm.

“Well, yes.”

Mike just shook his head.

“It’s natural to feel that way,” I said. “If there’s one thing I’ve learned about human nature, it’s this: Over a typical ten-year period, in any given year you’re going to love us twice, hate us twice, and be indifferent to us six times. It all depends on your investment returns for a given year.”

They smiled.

“You may think I’m joking, but I’m not. I speak from long experience. Over a ten-year period, the market typically goes up dramatically twice—these are the years you love us. Over that same period, the market typically goes down dramatically twice—these are the years you hate us. And then six of the ten times, you get an average return. Those are the years when you think we’re doing an okay job.” They laughed.

“I’m curious about something my brother-in-law said recently,” Mike said. “Doug, Rachel’s brother, is what you might call a do-it- yourself investor. He takes risks, but his view is that the greater the risk, the greater the reward. What do you think about that?”

“My investment philosophy is totally different from Doug’s. As I said before, I’m a conservative investor. Ask yourself something. Does Doug sleep well at night?”

Mike and Rachel laughed. “Funny you should ask,” said Rachel. “Doug’s never slept very well, and lately he’s been sleeping very poorly.” “Well neither could I if I took big risks in the market,” I said with a grin. “And from your risk profile I’m guessing the two of you couldn’t, either. Remember, in retirement, the risks just get that much greater.”

“Can you give us some specifics about how you would invest our money?”

“Sure. Proper asset allocation is the key to minimizing risk and maximizing return. The plan we put together for you implements a combination of mutual funds, stocks and stock dividends, bonds, GICs and cash. We also look at long-term care and critical illness insurance if it’s appropriate.”

“What about high-yield corporate bonds and stuff like that? Doug’s mentioned those things from time to time.”

“Those are also possibilities—but only if they make sense. The same goes for segregated funds, pooled funds, variable annuities, high-yield savings accounts and limited partnerships. There are a wide variety of investment vehicles; some fit, some don’t. Every client’s situation is different.”

“What about our accountant and lawyer? Before we implement the plan, should they be notified?

“Absolutely. We prefer it. That way we make sure your financial plan is airtight.”

“Our accountant, Charles, has a mind like a steel trap. He loves airtight plans.”

“Just keep in mind, a financial plan is a snapshot in time. It’s designed to let you know if you’re heading in the right direction. Life is unpredictable, so the true success of your plan lies in how well it’s monitored so it not only matches your current situation but your future goals and objectives as well.” I glanced at my watch. “There are two more risks we need to talk about. But it looks like we’ll have to save those for another meeting.”

“What are they?” Mike asked, ever inquisitive.

“Longevity and health. Health risks, you can guess. Longevity risk is the risk of outliving your money.”

“But our illustration indicates we won’t, doesn’t it?” Rachel asked. “Yes. But it’s important that you understand a little about how life expectancies work in retirement planning. Unfortunately, that’s going to have to be a topic for another meeting.”

“Charles is going to be thrilled to meet you!” Rachel said, smiling. “He hates risk even more than you.”

“I never said I hated risk. I just like to manage it wherever possible,” I said, smiling back.

Chapter summary

- Retirees should consider multiple retirement income

- Real returns are more important than nominal

- Projected retirement income is based on one’s life expectancy and lifestyle

- Only a quarter of retirees surveyed expect to have an income of $5,000 a month or greater.

- Rates of return are determined by examining the historical relationships among different asset classes as well as the optimal mix of growth to income assets in the

- Retirees face four big risks: Inflation, Market, Longevity and Health

Clay Gillespie is Managing Director of Rogers Group Financial, a Vancouver-based financial panning and advisory firm founded in 1973. This excerpt from Create the Retirement You Really Want is published here with the author’s permission.

Clay Gillespie is Managing Director of Rogers Group Financial, a Vancouver-based financial panning and advisory firm founded in 1973. This excerpt from Create the Retirement You Really Want is published here with the author’s permission.