Passing on Financial Prosperity while balancing Generosity and Responsibility

By Steve Lowrie, CFA

Special to Financial Independence Hub

Canada is in the midst of a historic intergenerational wealth transfer, with more than $1 trillion expected to pass from baby boomers to younger generations. For many families, the question isn’t just how much wealth to transfer but when and how to do so responsibly.

Should you give small, incremental gifts during your lifetime or leave a traditional large estate inheritance? Each approach has its merits, but both require careful planning to avoid unintended consequences like fostering dependency or jeopardizing your own financial security.

This blog introduces these two contrasting wealth transfer strategies. Along the way, we’ll explore how these approaches can be tailored to align with your goals while leveraging Canada’s tax rules and financial tools.

The Case for Incremental Giving

Giving while you’re alive allows you to see the impact of your generosity firsthand while offering opportunities to guide your children in managing their finances responsibly. In Canada, there’s no formal gift tax, making this approach particularly appealing.

For example, gifting funds for specific purposes — such as contributing to a child’s Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) or helping with a down payment on a home — can provide meaningful support without being life-changing. A parent might gift $10,000–$50,000 annually or on an irregular basis for specific needs, ensuring the funds are used purposefully while avoiding dependency.

Benefits of Incremental Giving:

- Tax efficiency: Cash gifts to a child that they use to contribute to their TFSA grow tax-free, and funds can be withdrawn without penalty.

- Accountability: Smaller and/or variable wealth transfer encourages children to not be reliant on wealth transfer and to develop financial discipline under your guidance.

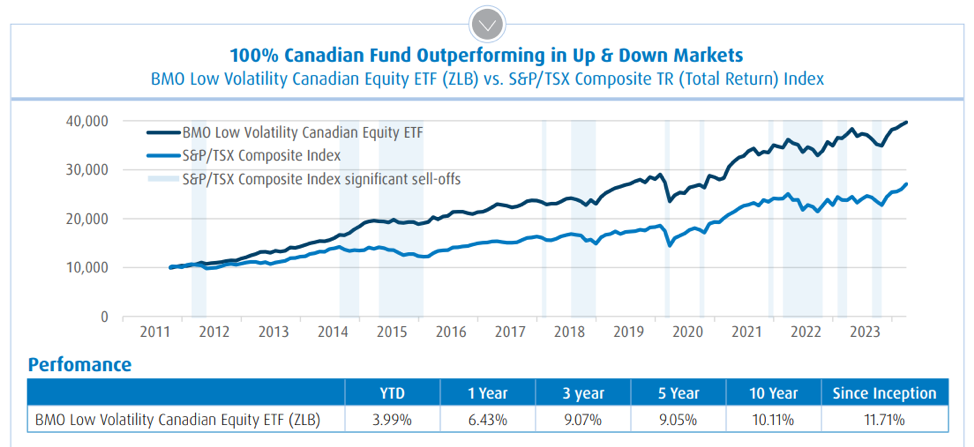

- Flexibility: You can adjust the size and timing of gifts based on your financial situation and outlook. It should be expected that every few years, financial markets will “correct” or pull back, although the route cause is always different. When this happens, you may choose to be more conservative in your giving to ensure your long-term financial well-being.

- Delight in their Enjoyment: By transferring wealth in stages while you are still around, you get to see the fruits of your labour passed on to the next generation, giving you the satisfaction of a well-lived life.

- Targeted Giving: The recipients of your wealth transfer might go through different ages and stages of their lives requiring very specifically timed financial influx. For example, you may consider a very different giving scenario for a 25-year-old just finishing university vs. a similar-aged child who has two children and is buying a house.

Considerations of Incremental Giving:

- Negative Impact of Over-Giving: Overzealous incremental giving can affect your long-term financial plan. It’s important to work with your financial advisor to plan conservative giving rather than putting the cart before the horse and realizing too late that you’ve over-extended your finances.

- Focus on Planning: It’s important to consider how you are moving the money – from where, to where, when, etc. – so that it doesn’t trigger negative consequences like capital gains on the giver. Or that needs to be taken into account when transferring your wealth.

- Attribution Rules: There are a complex set of laws that apply if you give money to minors so it’s important to be aware of these attribution rules as income earned by money given to the minor can be taxed to the parent.

- Expectation Misalignment: You may have a wealth transfer plan that works best for you and aligns with your long-term financial plan. However, your children may have pre-conceived thoughts of how and when the money will flow to them. So, it is important to discuss it so everyone can be on the same page, leaving less likelihood of misunderstandings.

- Conflict due to Giver Oversight: If you are giving money while you are alive, you get to delight in watching your children enjoy it. However, you also get the opportunity to observe and potentially be critical of how the money is being used. This can cause unintended conflicts and pressure on your relationship.

The Traditional Large Estate Gift

On the other hand, some families prefer to focus on building their estate and passing on a significant inheritance after death. This approach allows you to retain full control of your assets during your lifetime while simplifying the logistics of wealth transfer.

In Canada, there’s no inheritance tax, but all non-registered assets are subject to tax on all unrealized capital gains upon death. Proper planning — such as using life insurance or owning assets jointly — can help minimize these taxes and preserve more of your legacy for your heirs.

Benefits of a Large Estate Gift:

- Control: You maintain full access to your wealth throughout your life.

- Simplicity: A single transfer avoids the complexity of multiple smaller gifts over time.

- Tax Planning Opportunities: Tools like trusts or charitable donations can reduce estate taxes significantly.