By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

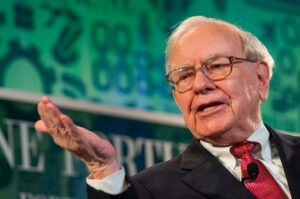

Warren Buffett is widely regarded as one of the best stock-pickers in history. Among the Oracle of Omaha’s most famous pieces of investment advice is “Rule No. 1: Never lose money. Rule No. 2: Never forget Rule No. 1.”

It goes without saying that when it comes to investing, it is impossible never to lose money. Even the longtime Berkshire CEO has occasionally taken his lumps. This begs the question of what Buffett meant by his statement. To best interpret the Oracle’s words, I took an actions speak louder than words approach and analyzed his historical returns over the past 30 years ending December 2022.

Unsurprisingly, Buffett & Co. trounced the S&P 500 Index, delivering a 13.1% compound annual rate of return vs. 9.6% for the benchmark. Had you invested $1 million with the Oracle rather than in the Index, your investment would have grown to $39,883,361, exceeding the benchmark investment’s value of $15,843,412 by a whopping $24,039,949 (it’s with good reason that people call him the Oracle!).

Moving beyond the headline numbers, the specific pattern of Berkshire’s returns is highly anomalous. In years when the S&P 500 Index had a positive return, Buffett’s performance tended to be undifferentiated. On average, for every 1% the index rose, Buffett’s holdings gained almost exactly the same amount. Clearly, the Oracle’s massive outperformance doesn’t come from knocking the lights out in good times.

In stark contrast, in years when the S&P 500 Index fell, Buffett gained 4.2% on average (no, that’s not a mistake!). This does not mean that the Oracle never loses money. In 2008, Berkshire declined 31.78% vs. 36.0% for the S&P 500. However, in down markets he has either tended to lose far less than the Index or not suffer any losses. The latter occurred during 2000-2002, when the Oracle gained 29.7% vs. a decline of 37.6% for the Index.

John Kelly & Fortune’s Formula: An Unsung Hero of Investing

Very few business school graduates or investment professionals have heard of the Kelly Criterion, which was developed in 1956 by American scientist John Kelly. Despite its relative obscurity and lack of mainstream academic support, the Kelly Criterion has attracted some of the best-known investors on the planet, including “Bond King” Bill Gross, Renaissance Technologies’ James Simons, Warren Buffett, and Charlie Munger (may the great man rest in peace).

The first well-known user of the Kelly Criterion is legendary investor and grandfather of quantitative finance Edward O. Thorp, who referred to it as “fortune’s formula.” He used Kelly’s theory to develop a system for calculating the odds and altering one’s bets accordingly in blackjack, which forever changed the game. Thorp then launched investment firm Princeton Newport Partners (PNP), which produced an annualized return of 15.8%, as compared to 10.1% for the S&P 500 Index. PNP achieved this return with 75% less volatility than the market and lost money in only three of its 230 months in operation.

The Kelly Criterion seeks to maximize long-term wealth by optimally adjusting the amounts of capital to commit to investments as their expected returns and risks fluctuate. Importantly, the formula dictates that you should increase your allocation when the odds are more favorable and curtail your commitment as the odds deteriorate. The imperative of adjusting one’s stance in response to changing circumstances was also espoused by the father of modern macroeconomic theory John Maynard Keynes. When criticized for being inconsistent during a high-profile government hearing, Keynes responded “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

Interestingly, this premise stands in stark contrast to the traditional approach to money management, whereby client portfolios maintain a fixed allocation to stocks, bonds, etc., regardless of changes in the market environment or economic backdrop.

What Does John Kelly Have in Common with Warren Buffett?

Having stated that “Our favorite holding period is forever,” Buffett is well known for buying quality companies and holding them for the long term. However, there is another, lesser-known side to the Oracle’s approach which harbors a more than subtle resemblance to Kelly’s.

In her book, “The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life,” author Alice Schroeder explains that Buffett’s best opportunities have always arisen during periods of crisis and uncertainty. In Buffett’s view, the opportunity cost of holding cash is low when compelling investment opportunities are few and upside is limited. Conversely, when downside is limited and compelling prospects are abundant (typically during the uncertainty that reigns during or after a market crash), the opportunity cost of holding cash becomes unjustifiably high. At such times, investors should aggressively deploy their cash holdings into assets that offer higher returns. This sentiment is well-summarized by Buffett’s assertion that “Cash and courage in a time of crisis is priceless.”

While many investors lack the courage and/or cash during such times, Buffett has historically possessed both. During the dot.com bust of 2002, he went on a shopping spree, scooping up companies in a number of sectors. Similarly, when global markets were in free fall in late 2008, Buffett made a number of significant investments in beaten down stocks.

Is the Oracle trying to tell us something?

As of the end of the third quarter of this year, Berkshire’s combined cash and U.S. Treasury holdings rose to a record $157.2 billion vs. $93 billion at the end of last year. For the first nine months of 2023, Berkshire was a net seller of $23.6 billion of equities vs. $48.9 billion of net purchases for the first nine months of 2022.

One need look no further than the current ratio of total U.S. stock market value to U.S. GDP to understand why Buffett is proceeding with caution. The Oracle has referred to this metric, which is known as the “Buffett Indicator” as “the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment”. As of the end of last October, the Buffett Indicator stood at 160%, which is 1.1 standard deviations above its historical trend line and in the top 14% of observations dating back to 1950.

These maneuvers do not necessarily imply that Buffett believes that a bear market is imminent. However, one could deduce that he is skeptical that stocks are poised to deliver meaningful returns over the near/medium term. Relatedly, the Oracle is likely of the view that holding larger than normal amounts of cash will not entail any opportunity costs given that rates have risen with a vengeance from their near-zero slumber.

The Oracle may be telling you that there won’t be much to miss and that better opportunities lie ahead. Given his track record, investors would be well-served to keep their FOMO (fear of missing out) instincts in check and their powder dry.

Risk is a No Fooling Around Game

According to legendary investor and father of systematic, rules-based investing Larry Hite, “Risk is a no fooling around game; it does not allow for mistakes. If you do not manage the risks, eventually they will carry you out.” Without exception, every successful investor is also a good risk manager. As Buffett’s track record demonstrates, he clearly meets this definition.

At Outcome, our algorithmically driven, machine learning based strategies have been specifically engineered based on sound risk-management principles which emphasize downside mitigation and consistency above all. This has enabled our clients to either mitigate or avoid losses in challenging market environments and compound their investments more effectively over the long term.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer of Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer of Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). Noah is frequently featured in the media, including his regular column in the Financial Post.

This blog first appeared in the November Outcome newsletter and is republished on the Hub with permission.