By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

Time is on my side, yes it is

Time is on my side, yes it is

Now you always say

That you want to be free

But you’ll come running back (said you would baby)

You’ll come running back (I said so many times before)

You’ll come running back to me

— The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones’ iconic hit, “Time Is On My Side,” is a testament to the power of patience. Its lyrics remind listeners that even though things can seem challenging, eventually everything will fall into place. Although this message may be conceptually appealing, it is increasingly ringing hollow with many investors.

Discipline is one of the most important principles of successful, long-term investing. Successful investors tend to stick to their knitting, even during times when this entails avoiding “hot” stocks and underperforming over the short or medium term.

However, even the most disciplined investors have their limits, which have been sorely tested over the past decade, courtesy of the blistering appreciation of mega-cap growth stocks. Such companies are largely represented by the aptly named Magnificent 7 (MAG7), which includes Apple, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Meta, Alphabet, and Tesla. The “pain trade” of prolonged, MAG7-related underperformance has been pervasive across investment styles, countries, and active management in general.

Value managers have been caught in the wrong place (or style) at the wrong time, to say the least. As the table below demonstrates, growth stocks have left their value counterparts in the dust over the decade ending in 2023.

S&P 500 Growth Index vs. S&P 500 Value Index: 2013-2023

This incredible dispersion has caused investment styles to dominate investment acumen to the point where even some of the best value managers have underperformed some of the worst growth managers. Alternately stated, there has been little, if anything that a value-based investor could have done to avoid getting outrun by the growth trade juggernaut that has dominated markets over the past 10 years.

The effect of the tremendous run of MAG7 companies has also had a profound effect on the relative performance of different countries and regions.

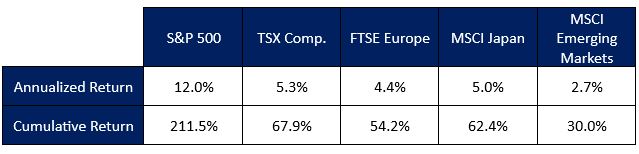

Comparative Returns: 2013-2023 (in USD)

To put it mildly, the S&P 500 Index, which its heavy exposure to MAG7 companies has turbocharged, has left non-U.S. indexes in the dust. The bottom line is that if you were underweight U.S. stocks, you were doomed to underperform.

Lastly, the MAG7 juggernaut has cast a dark shadow over active management (more on this later). According to Morningstar, during the decade ending in 2023, 90.2% of U.S. large cap managers underperformed their benchmarks. When it comes to active equity strategies, most clients’ experiences have been less than inspiring, if not disappointing.

From Big is Bad to Big is Beautiful

The dramatic outperformance of mega-cap companies over the past 10 years stands in sharp contrast to their longer-term historical pattern. Over the past several decades, underweighting the very largest stocks has been a winning bet. Since 1957, the 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500 have underperformed an equal-weighted portfolio of the other 490 stocks by an average of 2.4% per year.

The last decade has witnessed a violent reversal of this trend, with the largest 10 stocks outperforming by an impressive average annual rate of 4.9%. This dramatic break from history proves that the MAG7 are truly deserving of their name. Moreover, the MAG7’s jaw-dropping run has been uninterrupted, with 2022 being the single year in which they failed to outperform. This “blip” was quickly erased in 2023, with the MAG7 outperforming the S&P 500 by a whopping 60%.

Mega-Cap Outperformance: The Bane of Active management

The dramatic mega-cap outperformance over the past decade has proven particularly challenging for active management. Active managers tend to overwhelmingly underweight the largest stocks. This means they are by and large doomed to underperform when such companies outperform their peers.

Managers’ historical bias against mega-caps, as well as the latter’s longer-term historical underperformance, is well-justified. The performance of any stock can be attributed to (1) earnings growth and (2) valuation expansion or compression.

In general, it is more difficult for mega-cap companies to achieve above-average earnings growth than their smaller counterparts. When a company already has a substantial market share (as tends to be the case with mega-cap companies), it becomes difficult to maintain a high rate of growth. As such, the largest stocks generally achieve their size in large part due to multiple expansion. This has often left them in the precarious position of having to deliver exceptional earnings growth to produce good returns for their investors. This dynamic has historically proven costly, leading to underperformance.

Looking Ahead

To be fair, the MAG7 companies’ magnificence cannot be solely attributed to the performance of their stock prices. Their underlying fundamentals are impressive to say the least. Apple’s brand value provides it with a moat that protects it from both existing and potential competitors. The advertising power of Alphabet and Meta are nearly unassailable. Cloud infrastructure has been effectively duopolized by Amazon and Microsoft. Nvidia is the world’s premier GPU manufacturer, which places it in the enviable position of being able to capitalize on an AI-related explosion in demand for its products.

The bottom line is that the MAG7 are well-deserving of premium valuations. But the more relevant question is whether the size of their premiums reflects excessive optimism, and relatedly whether the MAG7 are likely to continue to deliver market-crushing stock performance going forward.

At the start of the decade, Apple, Microsoft, and Google had a combined P/E ratio of 15 vs. the market’s P/E of roughly 18.2, which provided them with a healthy base for future outperformance. These companies, alongside their MAG7 peers, also managed to grow their earnings at a ferocious clip, which further contributed to the phenomenal returns of their stocks.

As things currently stand, the MAG7 do not stand to benefit from relatively cheap valuations, with an aggregate P/E of 37 vs. 25 for the market. Moreover, some of the MAG7 companies may be exposed to significant regulatory/legal risks. Last month’s announcement by the Department of Justice that it is launching a lawsuit against Apple for allegedly limiting competition and harming consumers may be a harbinger of things to come. These types of headwinds may serve to compound the challenge of maintaining rapid earnings growth from a position of market share dominance.

The MAG7 companies also pose problems for passive, index investors from a diversification perspective. These companies currently have a combined weight in the S&P 500 Index of roughly 28% vs. 13% a decade earlier. If you don’t have a strong view that the MAG7 will continue to trounce the other 493 companies in the index, then indexing involves taking more risk (through lack of diversification) without any commensurate upside.

At the end of the day, nobody knows for sure whether mega-cap stocks will continue their record-beating run. However, the past several years notwithstanding, the historical track record of mega caps that are trading at a substantial premium to the market is far from pretty. Should mega-caps underperform, which seems like a reasonable longer-term bet, skilled active managers, and those with a value bias in particular, stand to outperform by a significant margin. Relatedly, we believe that our AI-based, value-oriented Canadian and U.S. equity income strategies are well-poised to add significant value over the next several years.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds. Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds. Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers.

Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). Noah is frequently featured in the media, including a regular column in the Financial Post and appearances on BNN.

This article first appeared in the March 2024 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished with permission.