So don’t ask me no questions

And I won’t tell you no lies

So don’t ask me about my business

And I won’t tell you goodbye

- Lynyrd Skynyrd

By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

I know virtually nothing about investing in private companies. However, I do know a thing or two about the theoretical and practical aspects of asset allocation and portfolio construction. In this vein, I will discuss the value of private equity (PE) investments within a portfolio context. Importantly, I will explain why PE investments may contribute less to one’s portfolio than is widely perceived.

Before I get into it, I am compelled to state one important caveat. Generalized statements about PE are less meaningful than is the case with public equities. The dispersion of returns across public equity funds is far lower than across PE managers. Whereas most long stock funds fall within +/- 5% of the average over a several year period, there is a far wider dispersion among underperformers and outperformers in the PE space. As such, it is important to note that the following analysis does not apply to any specific PE investment but rather to PE as an asset class in general.

The Perfect Asset Class?

PE allocations are broadly perceived as offering higher returns than their publicly traded counterparts. In addition, they are regarded as having lower volatility than and lower correlation to stocks. Given these perceived attributes, PE investments can be regarded as the “magic sauce” for increasing portfolio returns while lowering portfolio volatility. In combination, these attributes can significantly enhance portfolios’ risk-adjusted returns. However, the assumptions underlying these features are highly questionable.

Saturation, Lower Returns, & Echoes of Charlie Munger

It is reasonable to expect that average returns within the PE industry will be lower than in decades past. The number of active PE firms has increased more than fivefold, from just under two thousand in 2000 to over 9000 today. This impressive increase pales in comparison to growth in assets under management, which went from roughly $600 billion in 2000 to $7.6 trillion as of the end of 2022. It seems unlikely if not impossible that the number of attractive investment opportunities can keep pace with the dramatic increase in the amount of money chasing them.

Another reason to suspect that PE managers’ returns will be lower going forward is that their incentives and objectives have changed. The smaller PE industry of yesteryear was incentivized to deliver strong returns to maximize performance fees. In contrast, today’s behemoth managers are motivated to maximize assets under management and management fees. The name of the game is to raise as much money as possible, invest it as quickly as possible, and begin raising money for the next fund. The objective is no longer to produce the best returns, but rather to deliver acceptable returns on the largest asset base possible. As the great Charlie Munger stated, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

There are no Bear Markets in Private Equity!

It is also likely that PE investments on average have both higher volatility and greater correlation to stocks than may appear. The values of public equities are determined by exchange-quoted prices every single day. In contrast, private assets are not marked to market daily. Not only do PE managers value their holdings infrequently, but they also must employ a significant degree of subjectivity in determining the value of their holdings. Importantly, there is an inherent bias for not adjusting private valuations when public equities suffer losses.

On average, PE investments have nearly double the leverage ratios of their publicly traded equivalents. As such, there are strong grounds to suspect that PE holdings should be at least as volatile and perhaps more so than comparable stocks. How can it be that a company with nearly twice the leverage of another company in the same business with the same operating characteristics is less volatile? Put another way, the magic of infrequent, subjective valuations explains why there are no bear markets in private equity!

Alternately stated, it is not PE investments themselves, but rather the artificial smoothing of volatility that is responsible for the alleged lower volatility of private companies. I am not insinuating that there is any massive fraud afoot within the PE industry. However, I do believe that the marks reported by PE managers significantly understate the volatility of the asset class, certainly when compared to public equities. At the very least, one should take PE’s assumed low volatility and correlation assumptions with a hefty grain of salt.

I am not alone in these sentiments. In the December 2020 issue of The Journal of Investing, author Nicolas Rabener found that the volatility of private equity is understated as a result of smoothing, and that PE’s true risk-adjusted returns are comparable to those of public equities. Cliff Asness, founder of investment firm AQR Capital Management, which has almost $100 billion in assets under management, has been an outspoken critic of misaligned valuations in private markets. In his article “Why Does Private Equity Get to Play Make-Believe With Prices?,” he coined the term “volatility laundering” to describe the underestimation of risk in private equity.

Risks and Portfolio Implications

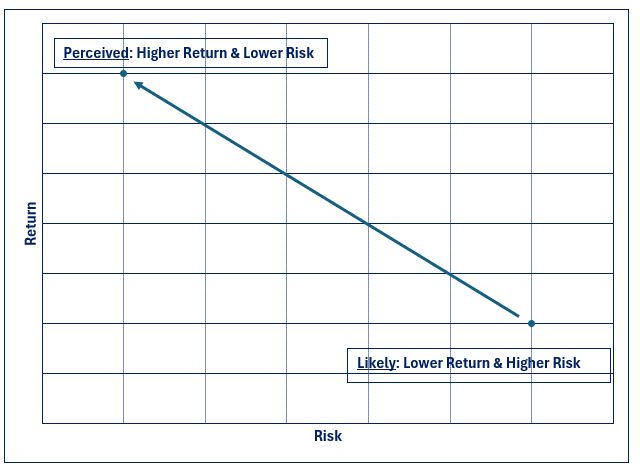

To the extent that PE investments will (1) deliver lower returns than in the past and (2) that their low volatility and lack of correlation to stocks are understated, investors are prone to allocating a higher than optimal weight to private assets within their portfolios.

Portfolio with PE Allocation: Perceived vs. Likely

The Value of Liquidity: A Moving Target

The value of liquidity, and by extension the extra return investors should demand in exchange for foregoing it, varies over time. In a more certain and stable environment, the ability to easily liquidate holdings is of less value. At such times, investors in illiquid assets should demand less of a return premium for holding them. By the same token, liquidity is of greater value at times of heightened uncertainty. In such environments, investors should demand a greater return premium from illiquid assets.

Although impossible to measure precisely, the global landscape is currently marred with greater uncertainty and risk than has been the case at any point in recent memory. Specific areas of concern include (1) multiple tensions and conflicts throughout the globe, (2) a potential long-term change in the global world order, (3) the effects of and solutions to climate change, (4) the massive debts and ongoing deficit spending of many western countries, and (5) the demographic consequences of aging populations.

All of these issues constitute a potential source for heightened instability and related market turbulence. Against this backdrop, investors would be well-served to err on the side of having a greater portion of their portfolios invested in liquid assets.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management Limited Partnership. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude).

Noah is frequently featured in the media including a regular column in the Financial Post and appearances on BNN. This blog originally appeared in the June 2024 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished here with permission.