By Steve Lowrie, CFA

Special to Financial Independence Hub

There are countless external forces influencing your investment outcomes: taxes, market mood swings, breaking news, etc., etc.

Today, let’s look inward, to an equally important influence: your own financial behavioural biases.

The Dark Side of Financial Behavioural Bias

Having evolved over millennia to secure our survival, our deep-seated behavioural biases precondition us to frequently depend more on “gut feel” than rational reflection. Sometimes, our instincts are life-saving, like when a car brakes hard right in front of you. Chemical reactions in the lower brain’s amygdala trigger you to brake too, even as your higher brain is still enjoying the scenery.

Unfortunately, these same rapid-fire triggers often hurt us as investors. When we make snap financial decisions that “feel” right but are rationally wrong, we tend to sabotage our own best interests. By recognizing these reactions as they occur, you’re more likely to stop them from ruining your financial resolve, which in turn improves your odds for better outcomes. Let’s explore some behavioural finance examples that you’ll want to prepare for…

Behavioural Finance Example #1: Fear and FOMO

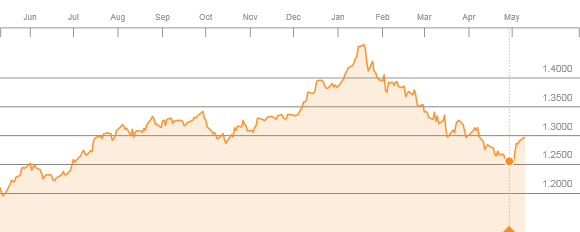

The point of investing is to buy low and sell high. So, why do so many investors so often do the opposite? You can blame fear, as well as Fear of Missing Out (FOMO investing). Time after time, crisis after crisis, bubble after bubble, investors rush to buy high by chasing hot holdings. They hurry to sell low, fleeing falling prices. They’re letting their behavioural biases overcome their rational resolve.

Behavioural Finance Example #2: Choice Overload and Decision Fatigue

Our brains also don’t deal well with too much information. When we experience information overload, we may stop even trying to be thoughtful, and surrender to our biases. We’ll end up favouring whatever’s most familiar, most recently outperforming, or least scary right now. When choosing from an oversized restaurant menu, that’s okay. But your life savings deserve better than that.

Behavioural Finance Example #3: Popular Demand and Survival of the Fittest

Inherently tribal by nature, we humans are susceptible to herd mentality. When everyone else gets excited and starts chasing fads, whether it is cryptocurrencies, alternative investments, or the other financial exotica-du-jour, we want to pile in too. When the herd turns tail, we want to rush after them. It’s like that old joke about escaping a bear: you don’t need to run faster than the bear; you just need to run faster than the guy next to you. In bear markets, this causes investors to flee otherwise sound positions, selling low, and paying dearly for “safer” holdings, rather than holding their well-planned ground.

Behavioural Finance Example #4: Anchor Points and Other Financial Regrets

Successful investors look past their occasional setbacks and remain focused on capturing the market’s long-term expected returns. But that’s hard to do, as we are often trapped by financial decisions regret. For example, loss aversion causes the average investor to regret losing money approximately twice as much as they appreciate gaining it. Similarly, anchor bias causes us to cling to depreciated holdings long after they no longer make sense in our portfolio, hoping against hope they’ll eventually recover to some arbitrary, past price. Ironically, you’re less likely to achieve your personal financial goals if you’re driven more by your financial regrets than your willpower.

Taking Charge of Your Financial Behavioural Biases

We’ve now looked at some of the damage done by behavioural biases. Once you know they’re there, you can at least minimize your exposure to them. Better yet, by using what behavioral psychologists call “nudges,” you can even harness your biases as forces for financial good. Following are two examples. Continue Reading…

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print