By Noah Solomon

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

Investment guru Howard Marks is the founder and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, the world’s largest investor in distressed securities. Since launching Oaktree in 1995, his funds have produced long-term annualized returns of 19%. According to Warren Buffett, “When I see memos from Howard Marks in my mail, they’re the first thing I open and read. I always learn something.”

As indicated by the title of his book, The Most Important Thing: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor, Marks believes that “the most important thing is being attentive to cycles.” In particular, he discusses the importance of knowing where we stand in various cycles. He contends that most great investors have an exceptional sense for how cycles work and where in the cycle markets stand at any given time. Lastly, Marks insists that investors who disregard cycles are bound to suffer serious consequences.

We live in a World of Relativism

There is a great saying about being chased by a bear, which states “You don’t have to run faster than the bear to get away. You just have to run faster than the guy next to you.”

In the context of investing, outperformance does not necessitate perfection. Success doesn’t come from always being right, but rather from being right more often than others (or from being wrong less often). Whether picking individual stocks or tilting your portfolio more aggressively or defensively, you don’t need to be right 100% of the time; you just need to be right more than others, which by definition leads to outperformance over the long-term. To this end, we have outlined some of our favorite concepts and themes which serve as guideposts for achieving this goal.

It’s all about Fear and Greed: Valuation just goes along for the Ride

The factors that drive bull and bear markets, bubbles and busts are too plentiful to enumerate. The simple fact is that more than any other factor, it is the ups and downs of human psychology that are responsible for changes in the investment environment. Most excesses on the upside and the inevitable reactions to the downside are caused by exaggerated swings in psychology.

Many investors fail to reach appropriate conclusions due to their tendencies to assess the world with emotion rather than objectivity. Sometimes they only pay attention to positive events while ignoring negative ones, and sometimes the opposite is true. It is also common for investors to switch from viewing the very same events in a positive light to a negative one within the span of only a few days (or vice-versa). Perhaps most importantly, their perceptions are rarely balanced.

One of the most time-honored market adages states that markets fluctuate between greed and fear. Marks adds an important nuance to this notion, asserting that “It didn’t take long for me to realize that often the market is driven by greed or fear. Either the fearful or greedy predominate, and they move the market dramatically.” He adds:

Investor psychology seems to spend much more time at the extremes than it does at a happy medium. In the real world, things generally fluctuate between pretty good and not so hot. But in the world of investing, perception often swings from flawless to hopeless. In good times, we hear most people say, “Risk? What risk? I don’t see much that could go wrong: look how well things have been going. And anyway, risk is my friend – the more risk I take, the more money I’m likely to make.” Then, in bad times, they switch to something simpler: “I don’t care if I never make another penny in the market; I just don’t want to lose any more. Get me out!” Buy before you miss out gets replaced by sell before it goes to zero.

Without a doubt, valuations matter. Historically, when valuations have stood at nosebleed levels, it has been only a matter of time before misery ensued. Conversely, when assets have declined to the point where valuations were compelling, strong returns soon followed. But it is important to distinguish cause from effect. Extreme valuations (either cheap or rich) that portend bull and bear markets are themselves the result of extremes in investor psychology. Importantly, human emotions are both fickle and impossible to precisely measure. Noted physicist and Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman articulately encapsulated this fact, stating “Imagine how much harder physics would be if electrons had feelings!”

Amnesia: The Great Enabler of Market Cycles

Another contributor to irrational investment decisions, and by extension market cycles, is the seemingly inevitable tendency of investors to engage in Groundhog Day-like behavior, forgetting the lessons of the past and suffering the inevitable consequences as a result. According to famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith, “Extreme brevity of financial memory” keeps market participants from recognizing the recurring nature of cycles, and thus their inevitability. In his book, A Short History of Financial Euphoria, he states:

When the same or closely similar circumstances occur again, sometimes in only a few years, they are hailed by a new, often youthful, and always supremely self-confident generation as a brilliantly innovative discovery in the financial and larger economic world. There can be few fields of human endeavor in which history counts for so little as the world of finance. Past experience, to the extent that it is part of memory at all, is dismissed as the primitive refuge of those who do not have the insight to appreciate the incredible wonders of the present.

Average and Normal: Not the same thing

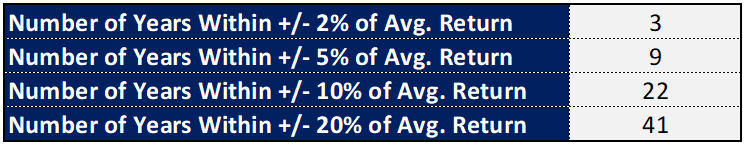

In many ways markets resemble the swinging pendulum of a clock, which on average lies at its midpoint yet spends very little time there. Rather, it spends the vast majority of the time at varying distances to either the right or left of center. In a similar vein, most people would be surprised by both the frequency and magnitude by which stocks can deviate from their average performance, as indicated by the table below.

Over the past 50 years, the average annual return of the S&P 500 Index has been 12.6%. The Index fell within +/- 2% of this number in only three of these years, within +/- 5% in only nine, and within +/- 10% in 22 (still less than half the time). Lastly, the index posted a calendar year return of +/- 20% of its long-term average return in nine of the past 50 years (18% of the time).

Also, when a pendulum swings back from the far left or right, it never stops at the midpoint, but continues to the opposite extreme. Similarly, markets rarely shift from being either overpriced or underpriced to fairly priced. Instead, they typically touch equilibrium only briefly before snowballing sentiment and resulting momentum cause a progression to the opposite extreme. Continue Reading…