By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

In his role as head of research at Merrill Lynch, Bob Farrell established a reputation as one of the leading market analysts on Wall Street. In his famous “10 Market Rules to Remember,” Farrell summarized his insights on market tendencies.

One of Farrell’s rules states, “When all the experts and forecasts agree — something else is going to happen,” which embodies the essence of contrarianism.

In this month’s missive, I explore the roots and causal factors underlying Farrell’s warning, drawing on historical examples. I also illustrate the potential benefits and pitfalls of going against the crowd. Additionally, I demonstrate that market sentiment is currently approaching levels that have historically preceded broad market declines. Lastly, I suggest that there are specific areas where investors should consider trimming exposure, realizing gains, and paying the taxman.

There is no shortage of historical examples of “sure things” ending badly. In the late 1990s, following two decades of above-average returns, both institutional investors and consultants broadly embraced the dangerous consensus that future stock market returns would be about 11%. Dissenters and naysayers were few and far between.

The basis for these forecasts was the extrapolation of recent results. Stocks had been delivering average annualized returns of 11%, therefore it was assumed they would do so going forward – simple. Few investors contemplated the possibility that the past 15 years were anomalous from a longer-term perspective. More importantly, there was little concern that an extended period of above-average returns might have been borrowed from future returns by pushing up valuations to unsustainable levels.

The sad ending to this ebullience was the first three-year decline in equities since 1930. For the seven years ending March 31, 2007, following the market’s peak in early 2000, the annualized return of the S&P 500 was 0.9%. Importantly, these subpar returns encompassed a bitter and painful peak-trough loss of about 50%.

A similar occurrence of widespread adulation ending badly occurred only a half-decade later in 2005, when everyone “knew” residential real estate was a “surefire” way to amass wealth. Zealots justified unsustainable values with oft-cited mantras such as “They’re not making any more land,” “You can live in it,” etc. This blind optimism pushed real estate prices to unsustainable levels which all but guaranteed the subsequent collapse and some painful experiences for the “it can only go up” crowd.

Sorry, Beatles – All You Need is NOT Love

More often than not, what is obvious to the masses is wrong. There are valid explanations, both financial and behavioral, that cause the things which everyone believes to be true to turn out to be untrue.

In July 1967, the Beatles released their famous single All You Need Is Love. With all due respect to John, Paul, George, and Ringo, nothing could be further from the truth in the world of investing. Specifically, the more popular a particular investment becomes, the less its profit potential, if for no other reason than if everyone likes something, such adulation is likely to be reflected in its price.

In what is referred to as the bandwagon effect, investors often become enthusiastic about a particular investment or asset class after it has already produced strong returns. Believing that past outperformance is a sign of strong future returns, the herd then hops en masse on the proverbial bandwagon. This widespread fervor then causes prices to overshoot any rational approximation of value, thereby setting the stage for inevitable disappointment.

In the world of investing, “everyone knows” should come with a “buyer beware” warning. Investments that are heralded as sure things are bound to be fairly priced at best and often become dangerously overvalued. Great opportunities lead to great prices, which by definition means their greatness has been paid for in full, stripping them of their greatness. Conversely, it’s only when people disagree that opportunities to achieve above-average returns exist.

Risk: Reality vs. Perception

Managing risk is at least as important as (and inextricable from) achieving decent returns. Not only do irrational sentiment and expectations result in poor returns, but also give rise to elevated risk. Risk evolves in the same paradoxical manner as returns. As an asset follows the journey from normal to over-owned and overpriced, not only does its potential return deteriorate, but its risk increases.

When everybody becomes convinced that something will produce spectacular returns, then by extension they also believe that it involves little or no risk. This perception often leads investors to bid it up to the point where it becomes excessively risky. In contrast, when broadly negative opinion drives all the optimism out of an asset’s price, its risk profile becomes relatively small. Put another way, investment risk tends to reside most where it is least perceived, and vice versa.

In the world of investments, Bob Farrell trumps the Fab Four. Good investments are generally associated with skepticism, indifference, and even neglect, which sets the stage for high returns with lower risk. Inversely, widespread acceptance and adulation sow the seeds of high-risk and poor returns.

No Good Deed shall go Unpunished

As is the case with many aspects of markets, both timing and patience play an important role in contrarian investing.

Investment trends regularly go to extremes. It is this very tendency that results in calamities and opportunities. Unfortunately, life for managers is not as simple as buying cheap assets and selling their overvalued counterparts. As John Maynard Keynes stated, “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Not only can overvalued assets remain stubbornly so for extended periods of time but can become even more overvalued before they ultimately come back down to earth. By the same token, undervalued assets can remain cheap and become even cheaper before any payoff materializes. Sentiment can be a self-fulfilling prophecy for an indeterminable amount of time before reversing, turning previously favored investments into assets non grata, and the subjects of yesterday’s scorn into tomorrow’s darlings.

Lord Keynes further cautioned on the dangers of contrarianism in his assertion that “Worldly wisdom teaches us that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” Managers who deviate from the herd based on sound economic principles run the risk of having their assets dwindle as clients lose patience. No good deed shall go unpunished, not only to the detriment of prudent managers, but also to that of the very clients who punish them!

Letting the Tax Tail Wag the Investment Dog

In Berkshire Hathaway’s 2007 annual report, Warren Buffett observed that “Of the ten non-oil companies having the largest market capitalization in 1965 – titans such as General Motors, Sears, DuPont and Eastman Kodak, – only one made it to the 2006 list.”

As previously stated, outperformance leads to hype, greed, overcrowding and overvaluation, which in turn results in underperformance. Similarly, underperformance leads to neglect, fear, under-ownership, and undervaluation, thereby giving way to outperformance. Cycles of excessive sentiment explain why yesterday’s outperformers become tomorrow’s underperformers (and vice versa). They are also the primary reason why reversion to the mean is arguably the most powerful force in modern finance.

Unfortunately, there is no free lunch when it comes to choosing between sound investing and the taxman. If you want to liquidate today’s winners to invest in tomorrow’s winners, there is no way around realizing gains and paying taxes. By the same token, if you are intent on deferring capital gains, this necessitates holding on to positions that may be past their prime and suffering the consequences while foregoing attractive opportunities.

We have done the math (ad nauseam), which clearly demonstrates that the economic damage from “lazy money” far outweighs the benefit of deferring taxes. Although realizing gains and triggering taxes is a bitter pill to swallow, many investors allow the tax tail to wag the investment dog to their detriment.

Even underperforming portfolios tend to rise substantially over long periods and harbor substantial unrealized gains. This fact, in combination with peoples’ bias against paying taxes today rather than in the future keeps investors inert. There by the grace of the tax code go poor managers!

Where Things Currently Stand

Great recent performance, fear of deviating from the crowd, and the inability or unwillingness to identify risk have time and again cost investors money, and likely will continue to do so in the future. Importantly, current gauges of sentiment are beginning to show signs that markets are getting ahead of themselves.

The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) Sentiment Survey regularly asks investors where they think the market is heading in the next six months. The results of the survey have historically served as a contrarian indicator. High levels of pessimism have tended to precede strong returns, while high levels of optimism have tended to foreshadow challenging market environments.

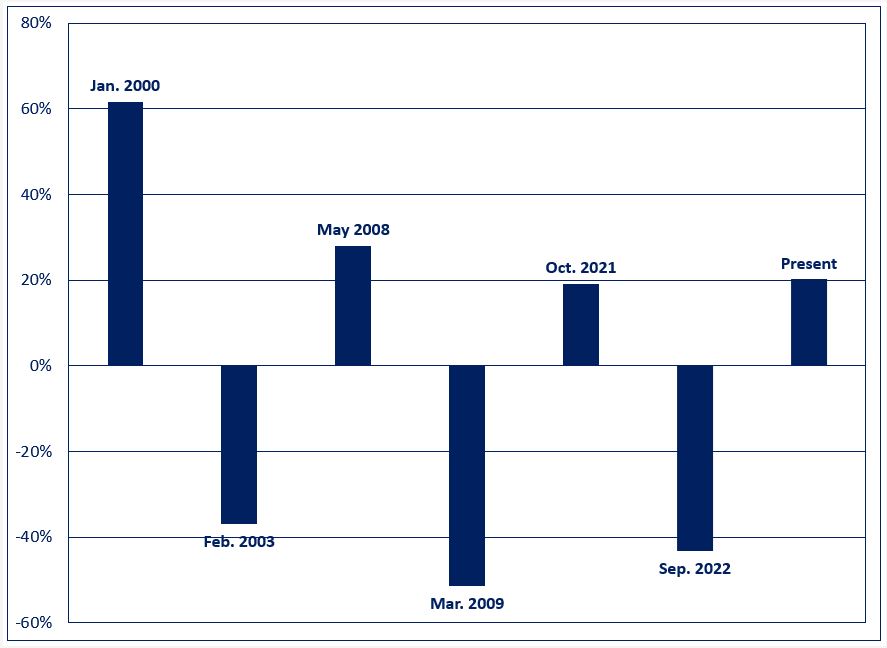

AAII Sentiment Survey: Percent of Respondents Bullish Minus Percentage of Respondents Bearish

As the graph above demonstrates, current sentiment is flirting with levels that foreshadowed losses in early January 2000, May 2008, or (to a lesser extent) October 2021. Interestingly, investors’ views were far more muted until early this month, when they registered one of the largest weekly jumps on record dating back to 1995.

There are and always will be some asset classes and segments of the market that are worthy of suspicion. The promise of AI notwithstanding, the ferocious rally in AI-related equities is cause for at least some degree of skepticism. In addition, asset classes such as private equity and private debt are being heralded as “cure all” for producing high returns without risk, despite the unlikely nature of that proposition.

At Outcome, our investment decisions are 100% based on rules-based processes derived from extensive analysis of historical data and machine learning. The underlying algorithms are never euphoric, despondent, greedy, or fearful. Admittedly, we will never produce spectacular returns based on speculative manias and investment fads, nor will we experience the related pain when such bubbles inevitably burst.

Our investment mandates are engineered to deliver benchmark-like returns in positive markets while outperforming in challenging investment environments. In tandem, these characteristics will produce better results through investment cycles over the long term.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer, Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah Solomon has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer, Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah Solomon has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers.

Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). This article appeared first in the May 2023 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished here with permission.