By Noah Solomon

Special to the Findependence Hub

Markets ended the first part of the year on a particularly sour note. Over the past four months, the MSCI All Country World Stock Index fell 12.9% in USD terms. High quality bonds, which have held up well in past episodes of stock market weakness, have failed to provide any relief, with the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond index falling 11.3%. Given the “nowhere to hide” atmosphere of markets, even a 60%/40% global balanced stock/bond portfolio suffered a loss of 12.3%.

Markets have entered a phase which differs from what we have witnessed over the past several years (and arguably over the past 40). In the following, we have done our best to share some of our most closely held beliefs about markets and investing, which we hope can serve as a guidepost for helping investors navigate the current market regime.

It just doesn’t matter … until it does

Most of the time, it doesn’t matter much whether your portfolio is positioned aggressively, defensively, or anywhere in between. Nonetheless, the fact remains that the big money is made or lost during the most violent bull and bear markets.

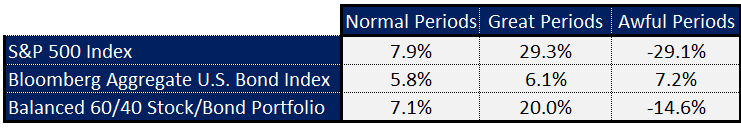

Defining a “normal” return for any 12-month period as lying between -20% and 20%, the S&P 500 Index behaved normally during 65.7% of all rolling 12-month periods between 1990 and 2021. Of the remaining 34.3% of periods, 29.0% were great (above 20%) and 5.4% were awful (worse than -20%)

Average 12-Month returns during Normal, Great, and Awful periods:

As the table above demonstrates, during normal periods there has not been a significant difference in average returns between the S&P 500 Index, the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, and a balanced portfolio consisting of 60% of the former and 40% of the latter. It is another story entirely during the 34.3% of the time when bull and bear markets are in their most dynamic stages. The good news is that there are some key signals and rules of thumb that offer decent probabilities of reaping respectable gains in major bull markets while avoiding the devastation from the worst phases of major bear markets.

Don’t fight the Fed

It is with good reason that the “Don’t fight the Fed” mantra has achieved impressive longevity and popularity. The monetary climate – primarily the trend in interest rates and central bank policies – is the dominant factor in determining both the stock market’s major direction as well as which types of stocks out or underperform (sectors, value vs. growth, etc.). Once established, the trend typically lasts from one to three years.

When central banks are cutting rates and monetary conditions become more accommodating, it’s a good bet that it won’t be long before stocks deliver attractive returns. In late 2008/early 2009, central banks responded to the collapse in financial markets by cutting rates aggressively and embarking on quantitative easing programs. This spurred a rapid recovery in asset prices. Similarly, to offset the economic fallout of the Covid pandemic, monetary authorities flooded the global economy with money, which acted as rocket fuel for stocks.

Conversely, when central banks are raising rates and tightening the screws on the economy, the effect can range from limiting equity market gains to causing a full-fledged bear market (not an attractive distribution of outcomes). Once the Fed began hiking rates in mid-1999, it wasn’t long before stocks found themselves in the throes of a vicious bear market that cut the S&P 500 Index in half over the next two to three years. Similarly, when the Fed raised its target rate from 1% in mid-2004 to 5.25% by mid-2006, it set the stage for a nasty collapse in debt, equity, and real estate prices. When it comes to stocks, bonds, real estate, or most other asset classes, it’s all fun and games until rates go up, which ultimately causes things to break.

Markets don’t care what you think: NEVER fight the tape

The importance of not fighting major movements in markets cannot be overemphasized. Repeat as necessary: Fighting the tape is an open invitation to disaster. This advice not only applies to the general level of stock prices, but also to the relative performance of different sectors, value vs. growth, etc.

Ignorance, which can cause people to fight market trends, is a valid justification for making mistakes during the earlier stages of one’s investment experience. But after suffering the consequences, there are neither any excuses nor mercy when you fight the tape a third or fourth time. The markets only allow so many mistakes before they obliterate your wallet.

The perils of following rather than fighting trends are well summarized by investing legend Marty Zweig, who compared fighting the tape and trying to pick a bottom during a bear market to catching a falling safe. Zweig stated:

“If you buy aggressively into a bear market, it is akin to trying to catch a falling safe. Investors are sometimes so eager for its valuable contents that they will ignore the laws of physics and attempt to snatch the safe from the air as if it were a pop fly. You can get hurt doing this: witness the records of the bottom pickers on the street. Not only is this game dangerous, it is pointless as well. It is easier, safer, and, in almost all cases, just as rewarding to wait for the safe to hit the pavement and take a little bounce before grabbing the contents.”

To be clear, there is no free lunch in investing. Being on the right side of major market moves necessitates getting whipsawed over the short-term every now and then. Inevitably, you will sometimes be zagging when you should be zigging and zigging when you should be zagging. You can get head faked into cutting risk only to watch in frustration as markets rebound, and you can also get tricked into becoming aggressive just before a decline in stock prices.

The stark reality is that only geniuses and/or liars buy at the lows preceding major uptrends and exit the very top before the onset of bear markets. Realistically, you can only hope to catch (or avoid) the bulk of the big moves. Getting whipsawed every now and then is a small price to pay for reaping attractive returns during the good times while avoiding large bear market losses.

You don’t need to be perfect. But you’d better be flexible

It doesn’t matter whether you are an aggressive or conservative investor, so long as you are a flexible one. The problem with most portfolios (even professionally managed ones) is that they are not flexible. Conservative investors tend to stick with defensive portfolios heavily weighted in high grade bonds, utility stocks, etc. They never reap huge gains, but they also never get badly hurt. Aggressive investors, on the other hand, often buy risky stocks or speculate in real estate using high degrees of leverage. They make fortunes in boom times only to lose it all in bad times when the proverbial tide recedes.

Neither approach is sound by itself. Being aggressive is okay, but there are nonetheless times to gear down and be a wallflower. By the same token, there are market environments in which even conservative investors should be somewhat aggressive.

A slap in the face is better than a pummeling: Manage your risk and cut your losses

The only consistent way to make money in markets is to run with profits and cut losses. Regrettably, when it comes to the latter, many investors haven’t learned their lesson. Ego prevents them from admitting a mistake. A slap in the face, as represented by a 15% price decline, is greeted with stubborn persistence to hang around for a severe pummeling. The stark reality is that a slap is easier to recover from than a bear market beating that can leave you in a poor position to pursue future gains once markets begin to recover.

There are only two types of dollars in the world. There are consumption dollars, which are spent on items such as clothes, cars, etc. The other type of dollars are investment dollars, which are deployed for the explicit purpose of generating profits.

Consumption dollars are static in nature – the dollars you spent yesterday on clothing, cars, etc. are more or less the same as those you will spend today or tomorrow (i.e., you get the same amount of stuff for the same amount of money). Conversely, investment dollars are chameleons – their character changes depending on where you are in the market cycle.

In frothy markets characterized by elevated valuations and widespread exuberance, investment dollars are weak – you either have to spend more of them than normal for a given stream of earnings or get less earnings than normal for a given amount of investment. On the other hand, investment dollars become powerful during challenging market environments when valuations are attractive and the crowd is despondent. During such times, earnings go on sale and there are bargains aplenty to be had.

With the conventional buy and hold approach to investing, both your asset mix and your balance between high risk, high potential reward and low risk, low potential reward stocks remain stagnant, regardless of changes in the market environment. This inflexibility ensures that you will bear the full brunt of bear markets and will sadly have little or no dry powder to go bargain hunting when the time is right.

The Economy and profits have nothing to do with stock prices (at least over the short-term)

There seems to be some inborn reasoning that better profits mean higher stock prices over the near-term, which is simply not true. Even if Wall Street/Bay Street strategists could predict economic growth for the next 1-4 quarters (admittedly a big reach, but please work with us here!), this doesn’t mean they could predict bull or bear markets.

The best gains tend to come in the first six months of a fresh bull market, when profits are actually declining. When economic conditions are dire, central banks cut rates, which stimulates the economy six to twelve months down the road. Conversely, some of the nastiest phases of bear markets occur when profits are rosy, economies are running at or above capacity, and unemployment is low. At this stage, monetary authorities raise rates, which causes a deterioration in corporate earnings several quarters down the road.

If you want to forecast the economy, look to the stock market. Stocks lead the economy, not the other way around. This is ironic given the parade of market pundits in the media opining on where markets will go based on their views of what the economy will do. Equities always look ahead, peaking well before the economy does and bottoming far in advance of recessionary troughs.

Bringing it all back home: Where we stand today

Markets have been, and may very well continue to be, in one of those rare periods when portfolio positioning can result in dramatically different outcomes.

In a world where capital gains become scarce (or nonexistent), high-flying, growth-oriented companies tend to underperform their value-oriented peers. In a similar vein, dividends (which are far less volatile than prices) take center-stage in terms of their share of contributions to overall portfolio returns.

In the current bout of market malaise, our data driven, machine-learning based Canadian Equity Income strategy has provided clients with an attractive place to take shelter. On a year-to-date basis through the end of April, the fund has returned 8.2% as compared to a decline of 1.3% for the TSX Composite Index. Since its inception in October 2018, the fund has outperformed over 99% of its peers, returning 59.2% vs. a return of 45.8% for the TSX Composite Index while exhibiting lower volatility and losses during challenging periods.

Our Global Tactical Asset Allocation Fund began dialing down risk aggressively in the final quarter of 2021. It has been shunning risk assets since the end of January, with 90% of its portfolio invested in short-term investment grade corporate bonds. This shift has enabled the strategy to suffer significantly lower losses than either the global stock index, the global bond index, or any combination of the two. Importantly, should stocks continue to plummet (after all, a 12.9% decline isn’t a disaster in the context of past bear markets), the portfolio is well-positioned to avoid a severe beating.

Chief Investment Officer, Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). This blog first appeared in the April 2022 edition of the Outcome newsletter is and is republished on the Hub with permission.

Chief Investment Officer, Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). This blog first appeared in the April 2022 edition of the Outcome newsletter is and is republished on the Hub with permission.