By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

When cash, high quality bonds, and other safe assets offer little yield, investors get caught between a rock and a hard place. They can either (1) accept lower returns and maintain their allocation to safe assets or (2) liquidate safe assets and invest the proceeds in riskier assets such as equities, high yield bonds, private equity, etc.

Using history as a guide, when faced with this dilemma many people choose the second option. This decision initially produces favorable results as the increase in demand for stocks pushes prices up. However, as this reallocation progresses, prices reach levels which are unreasonable from a valuation perspective, and the likely returns from risk assets do not compensate investors for their associated risk. At this juncture, committing additional capital to risk assets becomes akin to picking up pennies in front of a steam roller. For the most part, this narrative is what played out across markets following the global financial crisis of 2008.

Following the global financial crisis, near-zero rates pushed investors to take more risk than they would have in a normal rate environment, which entailed making outsized allocations to stocks and other risk assets.

Unable to bear the thought of receiving negligible returns on safe assets, people continued to pile into risk assets even as their valuations became unsustainable.

Had central banks not begun raising rates aggressively in 2022 to combat inflation, it is entirely possible (and perhaps even likely) that stocks would have continued their ascent, valuations be damned!

Instead, rising rates provided risk assets with some worthy competition for the first time in over a decade, which in turn caused investors to rethink their asset mix and shed equity exposure.

The Equity Risk Premium: A Stocks vs Bond Beauty Contest

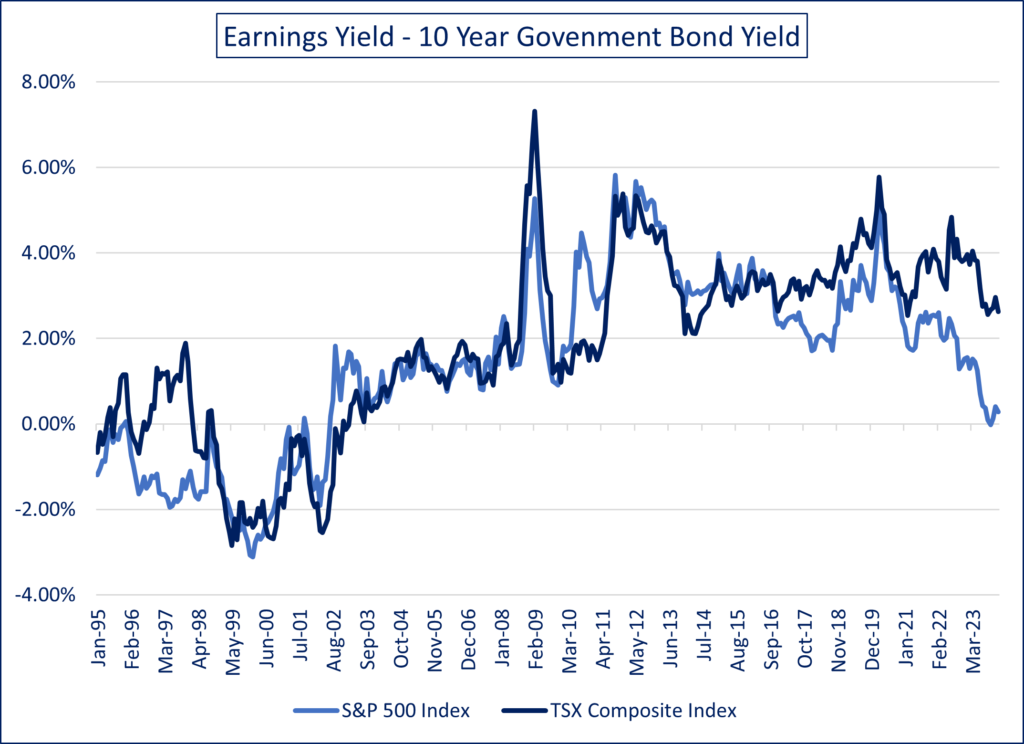

The equity risk premium (ERP) can be loosely defined as the enticement which investors receive in exchange for leaving the safety of Uncle Sam to take their chances in the stock market. More specifically it is calculated by subtracting the 10-year Treasury yield from the earnings yield on stocks. For example, if the P/E of the S&P 500 is 20 (i.e. earnings yield of 5%) and the yield on 10-year Treasuries is 3%, the ERP would be 2%.

Historically, stocks tend to produce higher than average returns following elevated ERP levels. Intuitively this makes sense. When valuations are cheap relative to the yields on safe assets, investors are getting well compensated for bearing risk, which tends to portend strong equity markets. Conversely, at times when stock valuations are rich relative to yields on safe assets and investors are getting scantily compensated for taking risk, lower than average returns from stocks have tended to ensue.

- At the end of 2020, the S&P 500 Index’s PE ratio stood at 20 (i.e. an earnings yield of 5%), which by no means can be considered a bargain. However, stocks were nonetheless rendered attractive by ultra-low rates on cash and high-quality bonds. It’s easy to look good when you have little competition!

- By the end of 2021, the Index’s PE ratio was above 24 (i.e. an earnings yield of 4.2%). Stocks were even less enticing than valuations suggested, given that 10-year Treasury yields had risen from 0.9% to 1.5%. This set the stage for a decline in both prices and valuations in 2022.

- From an ERP perspective, 2022’s decline in valuations did not make stocks less stretched vs. bonds. The contraction in multiples (i.e. increase in earnings yield) was more than offset by a rise in bonds yields, thereby causing the ERP to be lower at the end of 2022 than it was at the start of the year.

- In 2023, the S&P 500’s PE ratio expanded from approx. 18 to 23, which was not accompanied by any significant change in 10-year Treasury yields. By the end of the year, U.S. stock multiples had nearly regained the lofty levels of late 2021, despite the fact that Treasury yields had actually increased by over 2% during the two-year period.

- In contrast, the relative valuation of Canadian stocks vs. bonds currently lies at levels that are neither high nor low relative to recent history.

Low Rates: The Growth Stock amphetamine

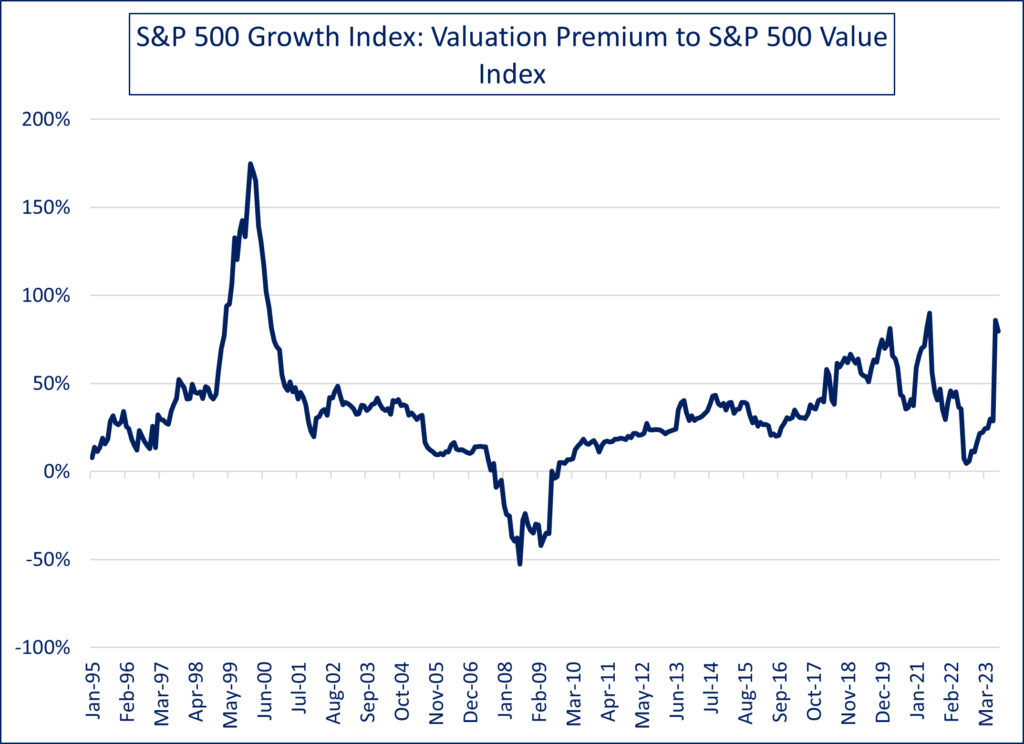

Growth companies, as the term implies, are those that are projected to have rapidly growing earnings for many years. Whereas an “old economy” stock such as Clorox or General Mills might be expected to grow its profits by 2%-10% per year, a juggernaut like NVIDIA could be expected to double its profits every year for the foreseeable future.

Compared to other companies, the projected earnings of growth stocks are heavily back-end loaded. Their anticipated future profits dwarf their current earnings. As such, investors in growth stocks must wait longer to receive future cash flows than those who purchase value stocks. All else being equal, growth companies become more attractive relative to value stocks when rates are low because the opportunity cost of the long wait is low (i.e. you’re not missing much by not having capital parked in safe assets). Conversely, growth companies become less enticing vs. value stocks when rates are high because the opportunity cost of the wait is higher.

- When central banks cut rates to zero in response to Covid, they fueled a tremendous rally in growth stocks, which left value stocks in the dust. From the end of March 2020 to the end of 2021, the S&P 500 Growth Index returned 106.1% vs. 69.6% for the S&P 500 Value Index.

- By the same token, when rates began to shoot higher in 2022, growth stocks underperformed significantly, with the S&P 500 growth Index falling 29.4% vs. a 5.2% decline in the S&P 500 Value Index.

- In 2023, although 10-year Treasury yields ended the year basically where they began, growth stocks outperformed by a healthy margin, with the S&P 500 Growth Index gaining 30% vs 22.2% for its value counterpart.

- From a big picture perspective, the multiple on growth stocks relative to value stocks is currently higher than it has been at any point since the start of the tech wreck in early 2000.

Where things currently stand

I fully appreciate why investors, when faced with near zero yields on safe assets in late 2021, continued to pour money into stocks despite elevated valuations. Where I run into difficulty is understanding why U.S. equities currently stand at similarly lofty multiples when yields on safe assets offer a very reasonable alternative. Alternately stated, I am somewhat baffled why one would be complacent about receiving historically little compensation for being invested in stocks vs. high quality bonds. By the same token, Canadian shares are far more attractively valued.

While I have no strong opinion regarding what will happen over the next 6-12 months, my sense is that over the medium-term U.S. stocks will not continue their recent streak of outperformance and perhaps will actually underperform.

Turning towards mega-cap growth stocks and the magnificent 7 phenomenon, I am of two minds. On the one hand, these are truly amazing companies. They are extremely well-managed and have delivered stupendous earnings growth over long periods of time. On the flip side, reversion to the mean has historically been one of the most powerful and consistent forces in modern markets, which does not bode well for the relative performance of growth stocks given that the valuation difference between growth and value stocks is at its widest levels since the start of the tech wreck of early 2000.

If forced to make a choice, my bet would be that mean reversion will win out over the medium term and that investors would be well served to tilt their U.S. stock exposure in favour of value over growth stocks.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers.

Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). Noah is frequently featured in the media including a regular column in the Financial Post and appearances on BNN.

This blog first appeared in the January 2024 Outcome newsletter and is republished on the Hub with permission.