By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

In response to rapidly accelerating inflation, central banks began raising rates aggressively at the beginning of 2022. Ever since, wild swings in bond markets have had a tremendous impact on virtually every single asset class.

This month, I examine the recent spike in rates from a historical perspective. Importantly, I will discuss the likely range of interest rates over the foreseeable future and the associated implications for financial markets.

When the Fed and other central banks were confronted with financial disaster in late 2008, they slashed interest rates to zero and deployed additional stimulative measures to ward off what many thought could be another Great Depression. Global rates then remained at levels that were both well below historical averages and the rate of inflation for the next 13 years.

In 2008, the runaway inflation of the 1980s and the painful medicine of record high rates that were required to subdue it were still relatively fresh in people’s minds. At that time, had you asked anyone what would be the most likely result of keeping rates near zero for over a decade, their most likely response would have been runaway inflation. And yet, inflation remained strangely subdued. According to most experts, this unexpected result is largely attributable to a relatively benign geopolitical climate and a related push toward global outsourcing.

This led to the notion of a “new normal” in which inflation was permanently expunged. Over the span of only 13 years, people went from fearing inflation to believing that it was a relic of the past unworthy of serious consideration. This false sense of comfort caused central banks and investors alike to be caught off guard in late 2021 when they realized that inflation had not been permanently vanquished but was merely hibernating.

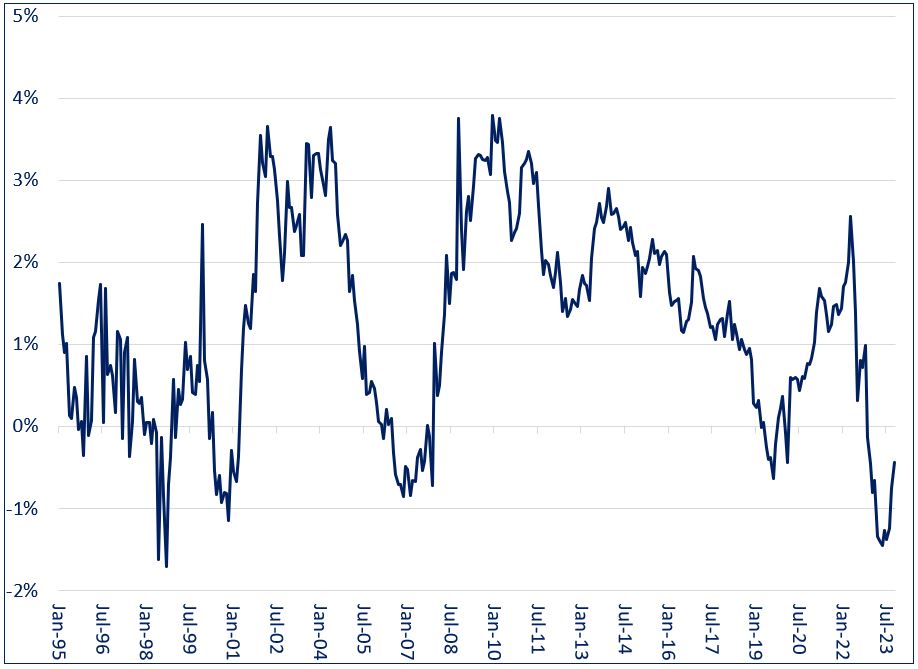

These sentiments were evident in bond markets. After rates were slashed to zero during the global financial crisis, investors were skeptical that they would remain there for long before stoking inflation. Longer-term rates remained well above their short-term counterparts, with the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries retaining an average 1.9% premium above the Fed Funds rate from 2009 – 2020.

However, 13 years of ultra-low rates with no sign of inflation allayed such fears, with the yield spread crossing into negative territory late last year and reaching a low of -1.5% in May of 2023. Even the rapid acceleration in inflation in late 2021 failed to fully disavow investors of the notion that the era of low inflation had come to an end, with current 10-year rates falling below their overnight counterparts.

10 U.S. Treasury Yield Minus Fed Funds Rate (1995 – Present)

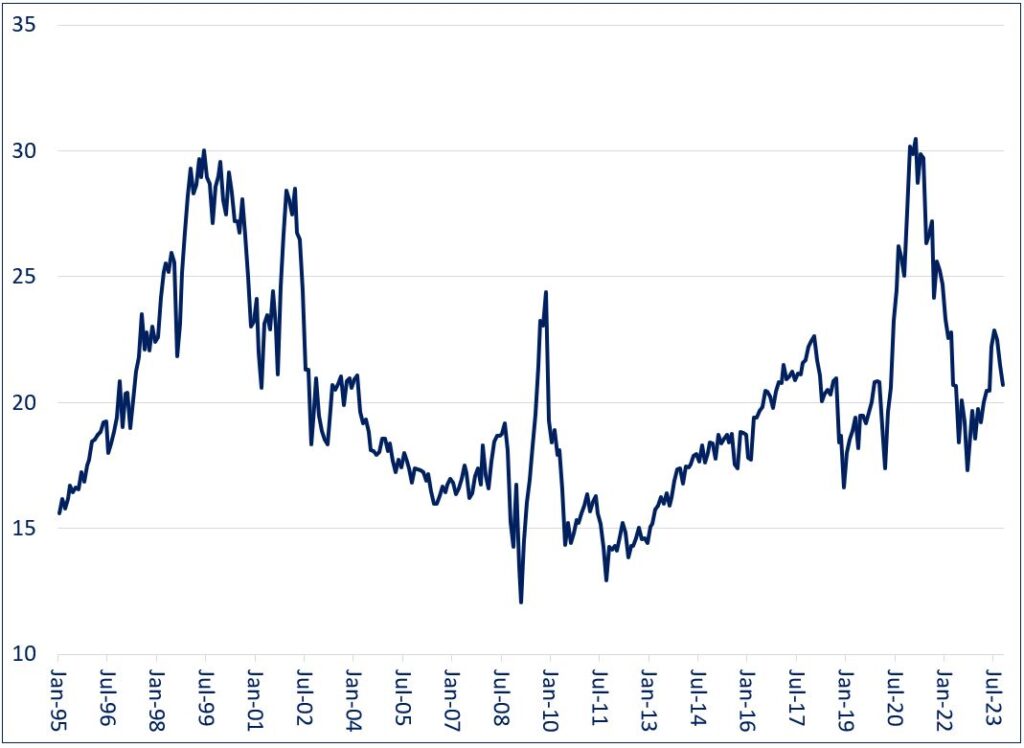

Equity markets danced to the same tune as their bond counterparts. When central banks cut interest rates to zero during the global financial crisis, investors were dubious that inflation would not soon rear its ugly head. Multiples remained relatively normal, with the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 Index averaging 16.4 for the five years beginning in 2009.

Over the ensuing several years, investors became complacent that the world would never again experience inflation issues, with the S&P 500’s P/E ratio climbing as high as 30 by early 2021. Multiples have since remained somewhat elevated by historical standards, indicating that markets have not fully embraced the fact that inflation may not be as well-behaved as what they are used to.

S&P 500 P/E Ratio (1995 – Present)

The Rising Tide of Declining Rates: Not to be Underestimated

According to legendary investor Marty Zweig:

“In the stock market, as with horse racing, money makes the mare go. Monetary conditions exert an enormous influence on stock prices. Indeed, the monetary climate – primarily the trend in interest rates and Federal Reserve policy – is the dominant factor in determining the stock market’s major direction.”

The 2,000-basis point decline in interest rates from 1980 to 2020 not only turbocharged aggregate demand (and by extension corporate revenues), but also dramatically lowered companies’ cost of capital. In tandem, these two developments were nothing short of a miracle for corporate profits and asset prices.

The goldilocks backdrop of low inflation and rock-bottom rates made almost everyone look like an investment genius, with stocks, private equity, venture investments, and pretty much anything else being taken on a joyride. Although the effects of this macroeconomic environment cannot be precisely quantified, I believe that it was responsible for a significant part if not the majority of investment gains over the past 40 years. According to author and economist Humphrey B. Neill, “Don’t confuse brains with a bull market.”

A New Reality

The trillion-dollar questions are:

(1) Will inflation return to target levels in the near-term?

(2) What is currently being reflected in asset prices?

The good news is that inflation is unlikely to be anywhere near as problematic as it was during the Volcker era, both in terms of persistence and magnitude. I have no reason to believe that interest rates will be materially different from where they are today at any point over the near to medium term.

The bad news is that a return to ultra-low rates is highly unlikely not only for the foreseeable future, but possibly for the remainder of many people’s investment careers. Central banks’ complacency regarding inflation has been shattered. Having been caught off guard by rapidly accelerating inflation in 2021, monetary authorities will be less aggressive in lowering rates in the event of an economic slowdown.

Moreover, the current geopolitical climate has become increasingly hostile, leading to deglobalization and onshoring. Lastly, the global push towards environmentally friendly forms of power, transportation, etc. is likely to put upward pressure on the prices of a multitude of raw materials. The upshot is that the one-way train of easy money and rapidly rising asset prices will not return anytime soon.

The Easy Way, The Hard Way, Or Somewhere In Between

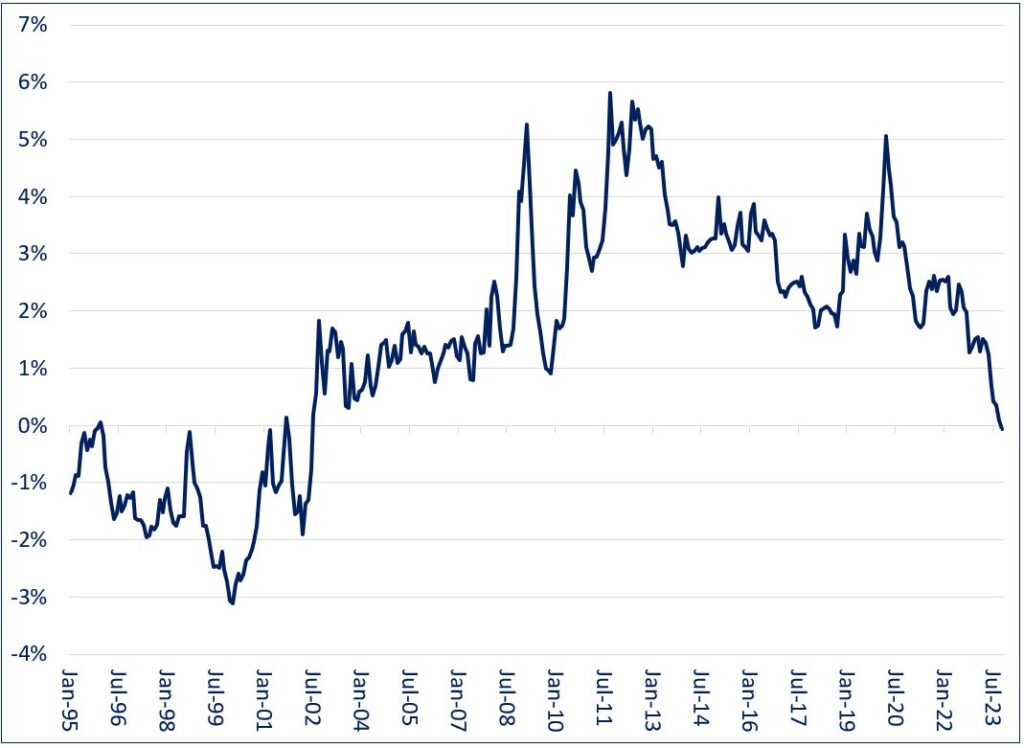

Looking at prevailing bond yields and equity market multiples, it appears that stocks are not currently priced for a “new normal” of elevated rates. The earnings yield of the S&P 500 Index currently stands at about 5%, which is roughly 0.3% higher than the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries. From a historical standpoint, this is well below the average difference of 1.5% since 1995 and is also lower than it has been at any point since the tech bubble and subsequent bust of the late 1990s – early 2000s. Simply put, investors are receiving very little incentive to leave the safety of Uncle Sam and take their chances with stocks.

S&P 500 Index Earnings Yield Minus 10-Year Treasury Yield (1995 – Present)

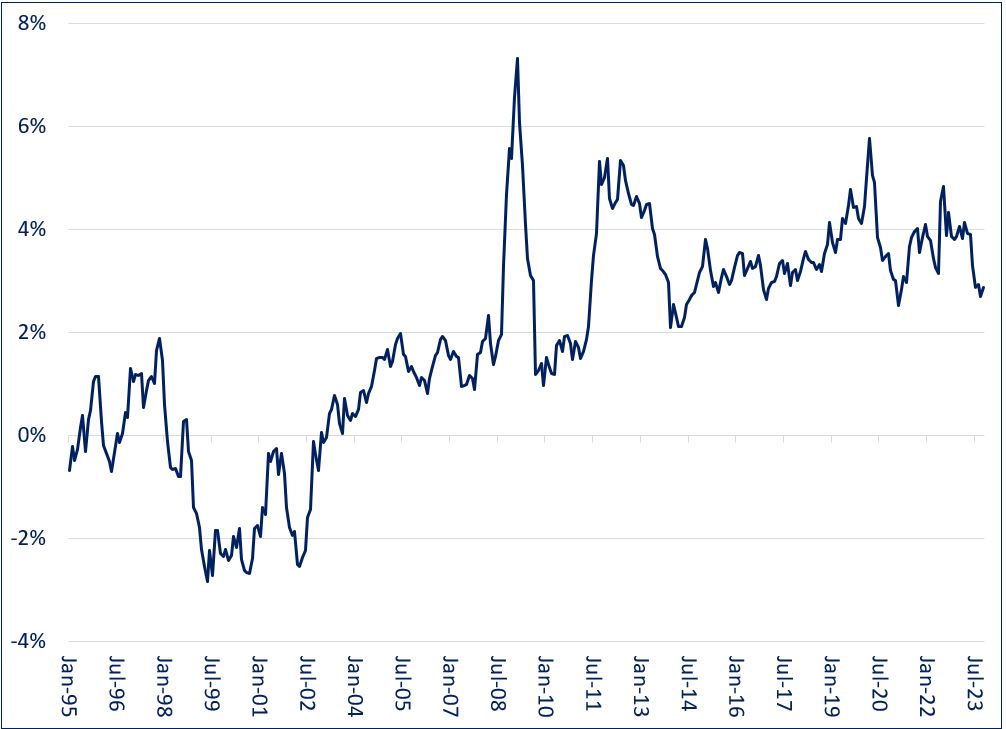

The valuation picture is far more favorable for Canadian stocks, with the current earnings yield of the TSX Composite Index standing roughly 3% above that of 10-year Government of Canada bonds. Not only is this spread far greater than that in the U.S. but is also higher than its average level since 1995 of 1.9%.

TSX Composite Index Earnings Yield Minus 10-Year Canadian Bond Yield (1995 – Present)

To be clear, high multiples relative to bond yields do not necessarily mean that stocks face inevitable losses. Granted, with no change in bond yields or earnings, the S&P 500 Index would need to decline by roughly 20% for the difference between earnings yields and 10-year Treasury rates to revert to its historical average.

However, there are several other, far more benign paths that markets can take. Even with no change in 10-year Treasury yields and/or no rapid acceleration in corporate earnings, stocks may experience a long-term benign adjustment whereby future gains are muted relative to earnings growth. Such a scenario would cause multiples to revert to historically average levels without any major turmoil.

Regardless of whether stocks undergo a turbulent or smooth transition, I believe that the investment environment for the next 5-10 years will not be nearly as favorable as that which prevailed during the easy money era of 2009-2021. It is more likely that investors will be confronted with both lower returns and higher volatility than what they have grown accustomed to.

According to (Warren) Buffett, “Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked.” Relatedly, I have a feeling that the change in the macro backdrop that we have seen will inevitably expose certain segments, with those which relied heavily on cheap leverage and rising prices suffering the most. With the future holding less upside and more downside than in years gone by, risk management should be awarded a more central role in investment decisions.

At Outcome, our algorithmically driven, machine learning based strategies have been specifically engineered based on sound risk-management principles.

Since its inception over five years ago, the Outcome Equity Income strategy has returned 46.5% vs 28.4% for the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index ETF (CDZ). According to S&P Global, our performance stands in sharp contrast to the vast majority of similarly focused mandates, 88.1% of which have underperformed the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index over the past five years. Importantly, the strategy has achieved this differentiation by outperforming in challenging market environments, making it well suited to more volatile markets.

Our Global Tactical Asset Allocation (GTAA) mandate has also exhibited strong defensive qualities, successfully protecting our clients from large losses during challenging markets, including late 2018, the Covid crash of early 2020, and more recently during last year’s bear market.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer, Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Noah Solomon is Chief Investment Officer, Outcome Metric Asset Management. As CIO of Outcome, Noah has 20 years of experience in institutional investing. From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds.

Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers.

Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude).

This article originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished here with permission.