By Ambrose O’Callaghan, Harvest ETFs

(Sponsor Blog)

In late August, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell caused a stir among the investing community when he provided the strongest signal yet that the U.S. central bank is gearing up for interest rate cuts starting in September.

At the time of this writing, we are just one day away from that crucial decision. So what will this mean for the yield curve, the direction of the Fed, how the change in policy is affecting markets, and the implications for Harvest Premium Yield Treasury ETF (HPYT:TSX) and the Harvest Premium Yield 7-10 Year Treasury ETF (HPYM:TSX) in the final third of 2024. Let’s explore!

How does the yield curve function?

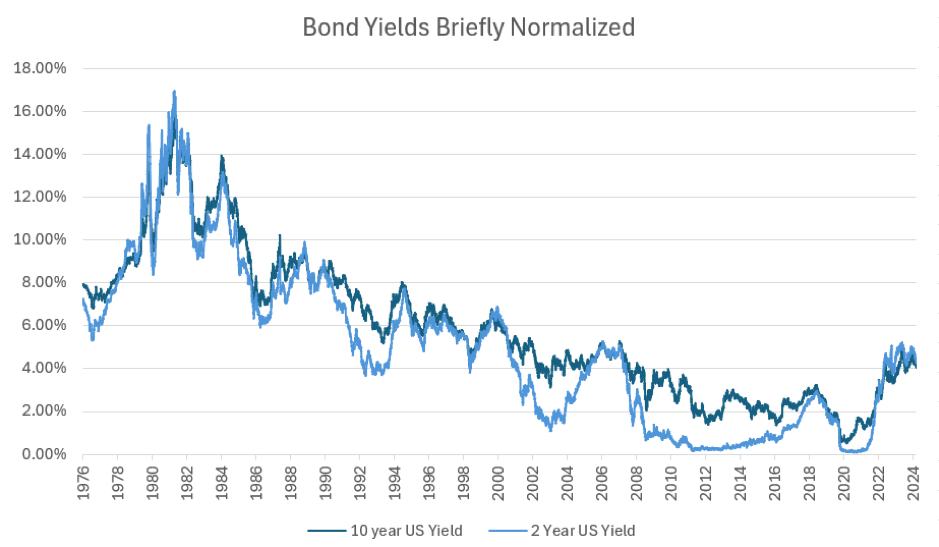

The yield curve, which is a representation of different bond yields across various maturities, can take varying shapes and curvatures. However, the most talked about is the shape of the yield curve in particularly one that’s either normal or inverted. A normal yield curve will have short-term bond yields that are lower than long-term bond yields. This encapsulates the time and risk premium associated with investing further into the future. However, in a period wherein central banks are seeking to slow economic growth/inflation, near-term rates will be raised in a manner that leads to higher short-term yields versus long-term yields. This is called an inverted yield curve, a much rarer occurrence.

Source: Bloomberg, Harvest Portfolios Group Inc., September 12, 2024

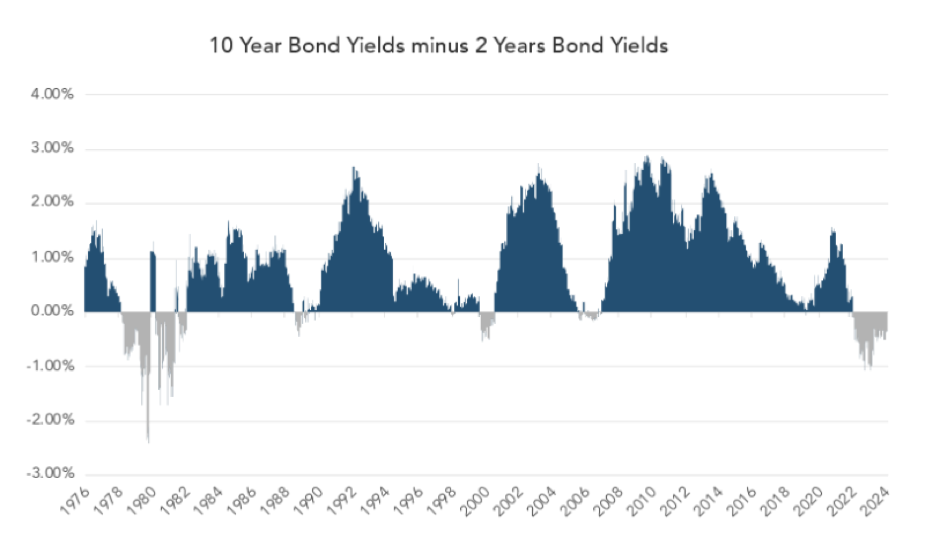

In practice, the difference between the 10-year yield versus the 2-year yield of government bonds is the go-to measure or gauge. The yield curve has been inverted for some time and became dis-inverted (Normal) in August 2024. That is a sign that shorter-term rates are coming down. This likely precedes meaningful interest rate cuts.

Source: Bloomberg, Harvest Portfolios Group Inc., September 12, 2024

What drives the Federal Reserve?

The Federal Reserve (Fed) has a dual mandate: to achieve maximum employment, and to keep prices stable. Despite taking on one of its most aggressive interest rate hiking cycles in history to regain price stability, inflation has failed to return to the target of 2%, albeit subsiding in recent months. The lower levels of inflation come with slowing economic data and weaker-than-expected jobs data, which belies the Fed’s goal of achieving maximum employment. So, what’s next?

With inflation coming down, the Fed members seem ready to cut short-term rates to alleviate the negative impact of higher interest rates on the economy. But before we get excited, it’s worth noting that the Central bank tools traditionally take time to filter through to the economy. Interest rate cuts may not have an immediate impact on the economy and broader markets but will filter over time.

Ultimately, this shift in policy should return the inverted yield curve to a normal yield curve.

Rate expectations: What is already priced in?

The next Fed rate announcement meeting is on September 18, and the market is already pricing in the first rate cut. The size of the cut is still up for debate, but it is likely to be 25 basis points, with a smaller chance that it could be larger at 50 basis points.

Looking further out to the Fed’s remaining two meetings for the rest of the year, the market expects the Fed to cut rates again. That would represent a total of 100 basis points of cuts expected by the end of 2024. Moreover, the market has priced in 10 rate cuts, or 250 basis points, of total interest rate cuts. These are priced in and expected to occur throughout 2025 with the ultimate destination of 3.00% on the overnight rate.

However, interest rates further out the yield curve have also recently moved down quite a bit. This is what’s known in bond-speak as a “bull steepening” — as the curve normalizes yields across maturities shift lower too, and thus bond prices move higher. Indeed, the narrative continues to shift toward the imminent start of this rate cutting cycle.

The 10-year yield was 3.65% at the time of writing. That is already down significantly – 137 basis points – from the peak of interest rates in October 2023.

The implications for the yield curve

What will happen to the yield curve going forward? Portfolio Manager Mike Dragosits, CFA, expects the yield curve to normalize due to several existing factors. The tightening cycle is ending, and the Fed is poised to embark on a rate-cutting cycle. So, this would mean that short-term bond yields may fall faster and stay relatively lower than long-term bond yields. Continue Reading…