By John De Goey, CFP, CIM

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

In the second half of August, the two countries that share the bulk of the North American continent independently signaled that they are shifting their economic courses and pursuing a public policy initiative which had been considered somewhat heretical until very recently. We are now left to reflect upon what it all means and how it will play out in the coming months.

Let’s re-cap. In mid-August, Bill Morneau resigned as Canada’s Minister of Finance and was swiftly replaced by the Prime Minister’s main political fixer, Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland. Concurrently, we learned that Trudeau had taken to seeking advice from Mark Carney. Carney has been the Governor of both the Bank of Canada and Bank of England, a senior consultant at Goldman Sachs, a Chairman of the Financial Stability Board and currently acts as the United Nations special envoy for climate action and finance.

He’s smart, connected and has shown repeatedly that he concurs with the thesis in Minister Freeland’s 2012 bestseller Plutocrats, which spells out just how rapidly income inequality has spread. There is now a wide consensus that first-world monetary policy has contributed greatly to this phenomenon. See my thoughts on the Cantillon Effect in a previous blog for more on why that is. For better or worse, Freeland, Trudeau and to some extent, even Carney are looking to craft a made in Canada policy response. Their perception is that the COVID-induced slowdown coupled with shockingly low rates has created a once in a lifetime opportunity to be bold.

To that end, the Prime Minister prorogued the federal legislature and, along with his newly-minted Minister of Finance, indicated that when the House resumed sitting, the Throne Speech would put major emphasis on the economy transitioning to a modern economy that is far greener than anything that has ever been seen in Canada previously. Parenthetically, this transition would also take pains to address growing inequality. Remember that the Trudeau government was first elected in 2015 with a mandate to look out for and champion ‘people in the middle class and those working hard to join it’.

By the end of August, we saw Jerome Powell, the head of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board, weigh in on how he, too, would be re-calibrating the Fed’s priorities to focus more on Modern Monetary Theory. It seems a convergence of thinking is now afoot. Both Canadian and American economic and public policy thought leaders are talking (and are almost certain to soon be acting) as though high deficits are of little consequence when interest rates are at generational lows. The Throne Speech is due in a month and it seems Powell is giving our federal government the political cover and international legitimacy they desire to do big things.

Alter fixed-income expectations downwards

I withheld my judgement on the policy prescriptions until I read the Throne Speech. [That came down Sept 23: editor. For this version of his blog on the Hub, De Goey adds “This is certainly a disconcerting trend. Governments around the world seem to be embracing the new orthodoxy of deficits don’t matter very much. My immediate concern is that it flies in the face of everything I was taught. Still, when economists like Paul Krugman say its no big deal, I have no good reason to doubt that it really is no big deal.”]

As a person who has spent his adult life as a fiscal / economic conservative, I have reason to be guarded. We all do. That said, I am genuinely open-minded about what lies ahead. Many reputable economists, such as Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, have written eloquently in the recent past about how we need to be less doctrinaire about debts and deficits.

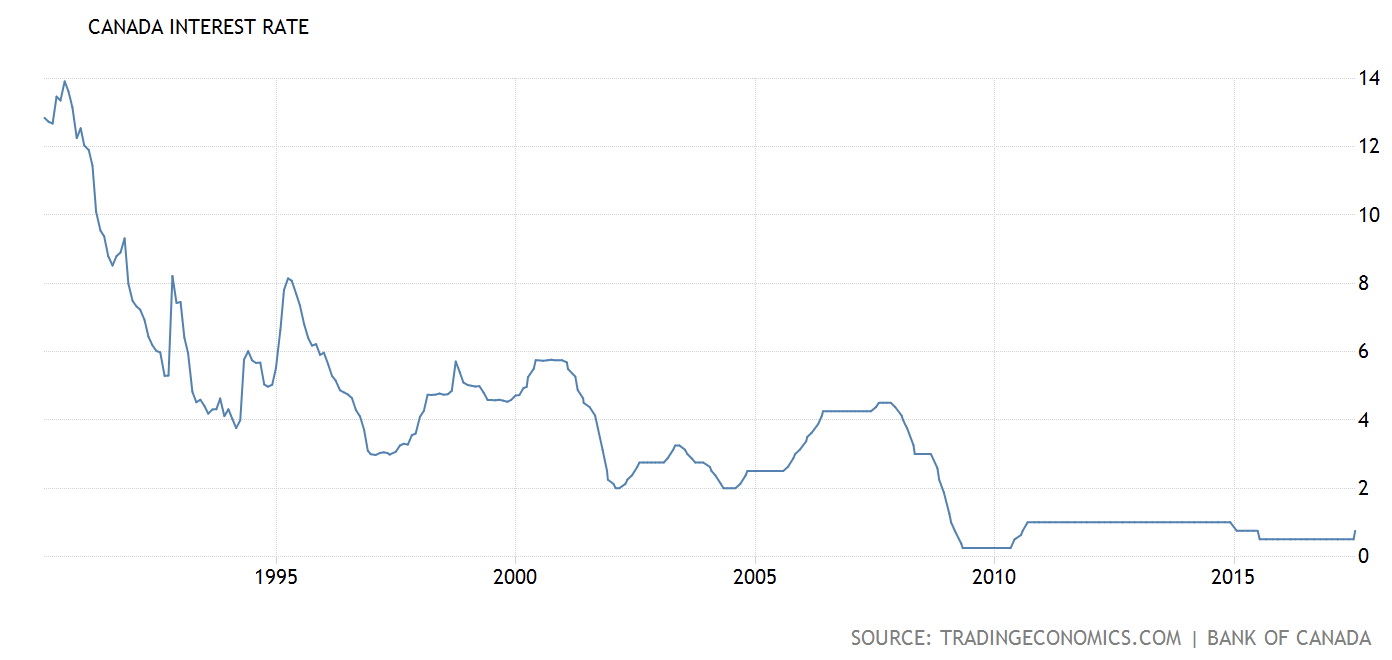

From a financial planning perspective, I cannot help but think that virtually everyone’s assumed rate of return for bonds, GICs and other debt instruments is almost certainly far too high. Irrespective of how our policy makers proceed, investors would be well-advised to alter their expectations accordingly. Rates are going to be very low for a very long time. At these debt levels, governments and central banks have no choice. Like it or not, we also have no choice but to manage our own expectations accordingly.

John De Goey, CIM, CFP, FP Canada™ Fellow, is a Portfolio Manager with Toronto-based Wellington-Altus Private Wealth Inc. This blog originally appeared on the firm’s “Newswire” site on Aug. 31, 2020 and is republished on the Hub with permission.

John De Goey, CIM, CFP, FP Canada™ Fellow, is a Portfolio Manager with Toronto-based Wellington-Altus Private Wealth Inc. This blog originally appeared on the firm’s “Newswire” site on Aug. 31, 2020 and is republished on the Hub with permission.