Special to the Financial Independence Hub

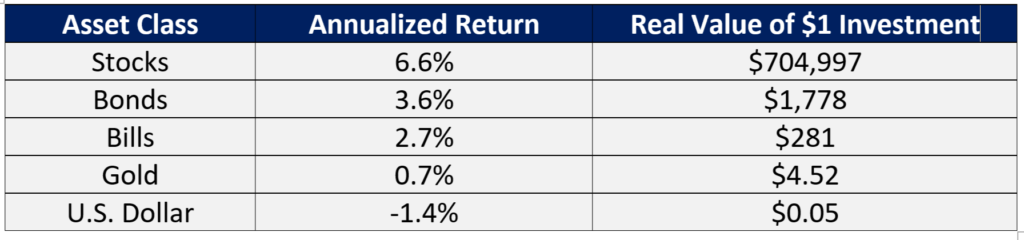

In Stocks for the Long Run, Wharton Professor Jeremy Siegel states “over long periods of time, the returns on equities not only surpassed those of all other financial assets but were far safer and more predictable than bond returns when inflation was taken into account.”

As the following table demonstrates, not only have stocks outperformed bonds, but have also trounced other major asset classes. The effect of this outperformance cannot be understated in terms of its contribution to cumulative returns over the long-term. Over extended holding periods, any diversification away from stocks has resulted in vastly inferior performance.

Real Returns: Stocks, Bonds, Bills, Gold, and the U.S. Dollar: 1802-2012

The All-Stock Portfolio: Better in Theory than in Practice

Notwithstanding that past performance is not a guarantee of future returns, the preceding table begs the question why investors don’t simply just close their eyes and hold all-stock portfolios. In reality, however, there are valid reasons, both psychological and financial, that render such a strategy less than ideal for many people.

The buy and hold, 100% stock portfolio is a double-edged sword. If you can (1) stick with it through stomach-churning bear market losses, (2) have a (very) long-term horizon, and (3) don’t need to sell assets for any reason, then strapping yourself into the roller-coaster of a 100% stock portfolio may indeed be the optimal solution. Conversely, it would be difficult to identify a worse alternative for those who do not meet these criteria.

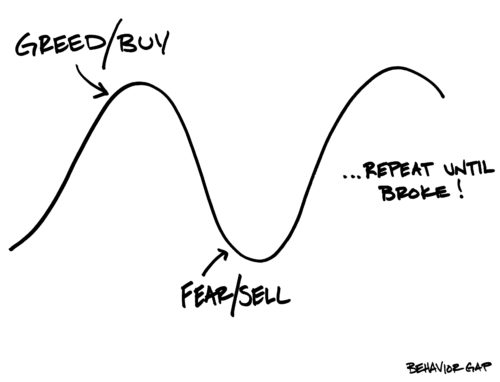

With respect to the emotional fortitude required to stand pat through bear markets, there is considerable evidence that many investors are simply incapable of doing this. Perhaps one of the best illustrations of this fact is Fidelity Investments’ flagship Magellan Fund under the stewardship of legendary investor Peter Lynch. From May 1977 to May 1990, Lynch managed to achieve an annualized return of 29.06% as compared to 15.52% for the S&P 500 Index. However, the average investor in the fund actually lost money during this period.

Many Magellan investors hopped on board when the fund was soaring and then jumped ship during difficult periods. This all-too-common misfortune is well-depicted by the following graph, which demonstrates how emotionally charged decisions can have a devastating effect on long-term performance.

Even if you have the emotional fortitude to stay the course through bear markets, there may be other reasons that compel investors to liquidate stocks, whether it be to fund living expenses, help their children buy homes, or invest in other opportunities. Unfortunately, the markets pay no heed to the convenience of mortals. If you are lucky, the need for cash will materialize at market peaks. Conversely, if you need liquidity near market troughs, then the effect is similar to that detailed in the graph above.

Bonds: the Good News & the Bad News

Historically, investors have used bonds to diversify their stock portfolios and reduce volatility. Investors typically set aside enough in bonds to weather periodic stock market downturns. Over the past several decades, the diversification value from holding bonds has been neutral to overall portfolio returns. During the bull market in bonds of the past 30 years, bond returns have just about kept pace with those of stocks. However, as indicated by the table at the beginning of this missive, this has not typically been the case.

Bonds can also be less stable than stocks and just as vulnerable to extreme losses. Since 1900, the maximum peak-trough loss in real terms for long-term U.S. government bonds was 68% as compared to 73% for U.S. stocks. Since 1807, the worst annualized 5-year performance for stocks of -11% was only slightly worse than the corresponding figure for bonds. When looking at 10-year holding periods, the worst stock performance was actually better than that of bonds. Investors who bought long-term government bonds in 1941 had to wait until 1991 before breaking even in real terms.

In his 2012 annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett stated:

“Bonds are among the most dangerous of assets. Over the past century these instruments have destroyed the purchasing power of investors in many countries, even as these holders continued to receive timely payments of interest and principal … Right now, bonds should come with a warning label.”

John Bogle, founder and former chairman of the Vanguard Group, found that since 1926, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes explains 92% of the annualized return that an investor would have earned had one held the notes to maturity and reinvested the interest payments at prevailing rates. The current yield on 10-year Treasuries of 2.78% is thus a good estimate of the future returns that investors can expect from holding intermediate term Treasury bonds.

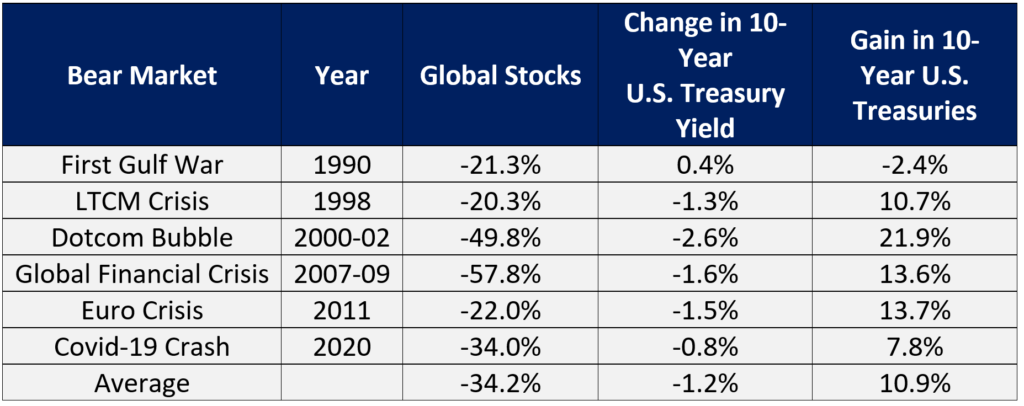

As indicated in the table below, bonds have provided significant diversification benefits during times of equity market turmoil in more recent bear markets.

The tendency of bonds to move inversely to stocks and provide portfolio diversification has not always been the case. Since 1973, stocks and bonds have been positively correlated more than 50% of the time. You need look no further than the first half of this year to realize that bonds can fail to deliver when stocks falter. During the first six months of 2022, bonds fell alongside stocks, with 10-year U.S. Treasuries declining 10.5% as global equities fell 20%.

Threading the Needle

On the one hand, a permanent allocation to bonds is likely to be a significant drag on portfolio returns over the long term. Moreover, bonds are not guaranteed to move in the opposite direction of stocks during periods of equity market turmoil. On the other hand, there can be little doubt that bond holdings tend to reduce portfolio volatility over shorter time periods.

History suggests that stable, dividend-paying stocks offer an efficient alternative to bonds. Over long-periods of time, income-producing stocks have generated higher returns than their non-dividend-paying counterparts while suffering shallower losses in challenging periods. Over the past 20 years ending June 2022, the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index has produced a total return of 624.7% as compared to 468.6% for the S&P 500 Index. Over the same time period, the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index returned 555.7% vs. 355.0% for the TSX Composite Index.

In addition, dividend-paying companies tend to hold up better than their non-dividend paying peers in challenging environments. During the first six months of 2022, the S&P 500 Index suffered a loss of 20.0% compared to a decline of only 12.2% for the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index. Looking north of the border, the TSX Composite Index fell 9.9% vs. a decline of 5.3% for the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index.

Our algorithmically driven approach to investing has succeeded in amplifying these benefits. From a capital preservation perspective, our Canadian equity income strategy has returned 5.1% on a year-to-date basis through the end of July vs. a decline of 5.7% for the TSX Composite Index and a loss of 0.7% for the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index.

Importantly, our ability to protect our clients in challenging periods has not come at the expense of long-term performance. Since the fund’s inception in October 2018, it has returned 54.6% vs. 37.6% for the TSX Composite Index and 41.3% for the TSX Dividend Aristocrats Index.

As Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management, Noah Solomon has 20 years of experience in institutional investing.From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds. Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). This blog first appeared in the July 2022 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished on the Hub with permission.

As Chief Investment Officer for Outcome Metric Asset Management, Noah Solomon has 20 years of experience in institutional investing.From 2008 to 2016, Noah was CEO and CIO of GenFund Management Inc. (formerly Genuity Fund Management), where he designed and managed data-driven, statistically-based equity funds. Between 2002 and 2008, Noah was a proprietary trader in the equities division of Goldman Sachs, where he deployed the firm’s capital in several quantitatively-driven investment strategies. Prior to joining Goldman, Noah worked at Citibank and Lehman Brothers. Noah holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated as a Palmer Scholar (top 5% of graduating class). He also holds a BA from McGill University (magna cum laude). This blog first appeared in the July 2022 issue of the Outcome newsletter and is republished on the Hub with permission.