By Larry Bates

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

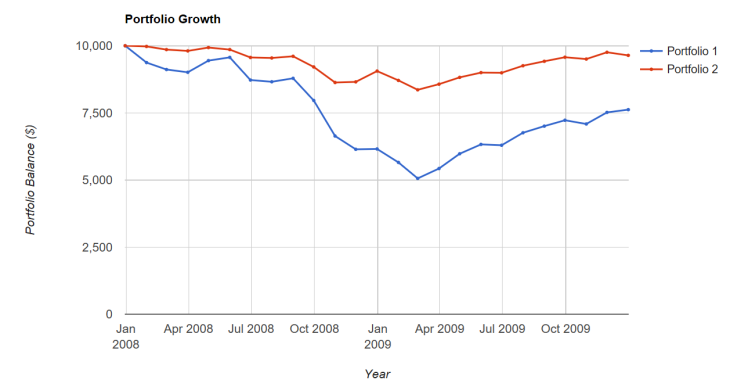

The big Canadian banks, and by extension the entire Canadian financial industry, occupy a position of paternalistic authority that too many individual investors respect unquestioningly, and even appreciate to some extent. The industry brilliantly capitalizes on a combination of poor understanding of fees, deep loyalty, and misplaced trust by charging Canadians the highest mutual fund fees in the world. This leaves most Canadian retirement investors with 100% of the market risk but only about 50% of market returns.

The impact of these high (and often unseen) investment fees on Canadian retirement accounts is more than a consumer issue, it is a major social issue of our time.

Government pensions will not be nearly enough to provide a satisfactory retirement lifestyle for most Canadians, and guaranteed employer pensions are rapidly becoming a thing of the past. In order to live well in retirement, you now likely need to build significant savings and make those savings grow through investment. So,while previous generations of Canadians with guaranteed pensions could casually observe the markets from the sidelines, most of us today must participate directly in the markets to secure a comfortable retirement.

In other words, you, and only you, have the burden of responsibility to get investing right. But the structure and practices of the investment industry continue to conspire against the ability of the average investor to succeed, to maximize that retirement nest egg. This compromises not only the financial well-being of individual Canadians, but also the health of our retirement system and of our society as a whole.

But there is good news. There are a growing number of very efficient, low-cost investment products such as index ETFs and services such as online discount brokers and “robo-advisors” that enable Canadians to keep a much larger share of their investment returns where they belong … in their retirement accounts. And these lower-cost products and services are offered by the big banks as well as several independent institutions. But you need to know the basics in order to take advantage of these opportunities and build bigger nest eggs. Continue Reading…