By Mark Yamada and Ioulia Tretiakova

By Mark Yamada and Ioulia Tretiakova

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

Nobel laureate William Sharpe described managing retirement assets as the “nastiest hardest problem in finance.” Living longer on a fixed pool of capital is only the start of a problem complicated by the myriad of possible personal and family needs and obligations that develop over a lifetime.

The need

Demographics are driving big change in the retirement market. Not only will Gen Y workers have fewer opportunities to save for retirement because of high predicted job turnover and reduced access to workplace pensions, but retiring baby boomers are being abandoned by the very industries created to serve them.

The pension, mutual fund and wealth management industries are direct responses to boomers joining the work force, but fewer retiring boomers meet the criteria for investment advisors who are compensated for growing assets. Retiree portfolios don’t get contributions and many are too small to qualify as brokerage minimums rise. Most mutual fund fees are too high for this cohort for whom costs are more important than ever before. The number of advisors is also shrinking, not only because of compensation and compliance pressures but also because advisors too are retiring.

Saving more, starting earlier and taking more risk are the accepted ways to improve retirement outcomes. Two or more of these options may no longer be available for retirees. A growing crisis in retirement savings is stretching an already extended social welfare system and new thinking is needed if disaster is to be averted.

Solutions not products

Our research motivation (Journal of Retirement and two Rotman International Journal of Pension Management papers) is a belief that investing can be improved to solve problems. The pension problem, for example, is best resolved by focusing on what workers really want, reliable replacement income in retirement rather than trying to pick the best performer every period. Consumers today want solutions. The investment industry is still about products.

Just as someone who only owns a hammer sees every problem as a nail, the industry has a singular focus on “maximizing returns.” This sounds good, but anyone using Google maps knows the fastest route to a destination is not necessarily the shortest. UPS routes deliveries to avoid turns against oncoming traffic to reduce accidents and delays waiting for gaps. Their drivers make 90% right hand turns and experience shorter delivery times, lower fuel consumption and operate smaller fleets. What if investment portfolios could similarly be routed more efficiently to correct destinations?

Autonomous portfolios

The self-driving automobile that protects passengers from immediate risks and routes itself to a predetermined destination provides a template for an autonomous portfolio.

Getting to a destination is a different strategy than going as fast as possible all the time. For starters, brakes and steering are needed not just an accelerator pedal. Maximizing returns, the investment industry’s primary approach, is about going fast. If your strategic asset mix is 65% stocks and 35% bonds, your advisor will periodically rebalance to this mix. If stocks go down, she will buy more stocks. This sounds like the right thing to do, and it is, if your investing time horizon is long enough to make back accelerating loses over the next market cycle; your portfolio is throwing money at a falling market after all. For an aging population in general and retiring baby boomers in particular, this is an increasingly risky and unpalatable proposition.

How we can do it

To protect portfolios we keep risks as constant as possible. When volatility rises, some risky assets, like stocks, are sold and less risky ones, like bonds, are added. When volatility falls, we add riskier assets. The critical effect is avoiding big losses. Statistically this is like card counting in the casino game of blackjack. When volatility is higher than average, the deck is stacked against the player. This means we expose portfolios primarily to markets that are favorable. It’s an unfair advantage but it’s legal! Continue Reading…

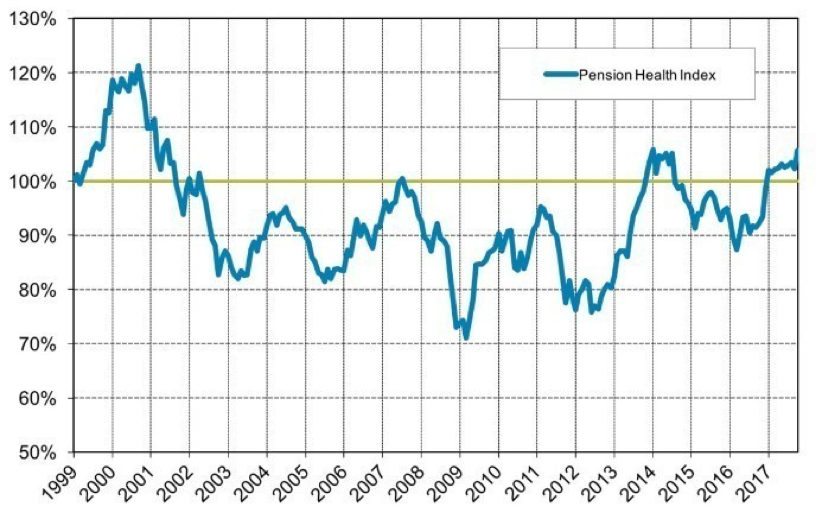

Source: Mercer Pension Health Index published October 2, 2017

Source: Mercer Pension Health Index published October 2, 2017