By Bob Lai, Tawcan

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

As many of you know, we have been busy adding new capital and buying dividend paying stocks over the last few years. During the COVID-19-caused short recession last year, our portfolio was down as much as $250,000. We didn’t panic and liquidate our portfolio. Instead, we saw the recession as an opportunity to buy discounted stocks and we added $115k to our dividend portfolio.

I’m a believer in time in the market, rather than timing the market. Therefore, we try to be fully invested in the stock market as much as we can. We use our monthly savings to add new shares and take advantage of any downturns. We also strategically move any long term savings for spending account to buy dividend paying stocks whenever there are enticing buying opportunities. We then “put back” money in the LTSS account over time.

Although we are in the accumulation phase of our financial independence retire early journey, I have done a few calculations and scenarios to plan out our early withdrawal strategies and plans. But they are what the names suggested – strategies and plans. Nothing is written in stone and things can certainly change by the time we decide to live off our dividend portfolio.

Recently Mark from My Own Advisor appeared on Explore FI Canada to discuss FI Drawdown Strategies. Since Mark is a few years ahead on the FIRE journey than us, or FIWOOT (Financial Independence Working on Own Terms) as Mark calls it, it was great to hear about what Mark is thinking and the considerations he has.

Speaking of living off dividends and early withdrawal strategies, it was really awesome to be able to pick on Reader B’s brain on this topic:

- Living off dividends – How I’m receiving $360k dividends a year & paying almost no taxes

- Living off dividends – My $360k per year dividend income

After listening to the Explore FI Canada episode, I thought about our early withdrawal strategies. Are there effective ways to minimize taxes so we get to keep more money in our pocket?

For Canadians, we can receive CPP and OAS when at age 65. I have not included CPP and OAS in our FIRE number calculation because I always considered them as the extra income and didn’t want to rely on them during retirement. Having said that, are there things we can do to receive the full CPP and OAS amounts without clawbacks?

A few things to note before I go any further…

- We plan to live off dividends and only sell our principal if we absolutely have to.

- We plan to pass down our portfolio to our kids, future generations, and leave a lasting legacy.

- Ideally it’d be great to be able to pass down our portfolio to future generations. But we also don’t want them to take money for granted. Therefore, we are also not against the idea of not passing anything to future generations.

- I’d love to write a million dollar cheque and donate it to a charity.

Our Investment Accounts

Our dividend portfolio comprises the following accounts:

- 2x RRSP

- 2x TFSA

- 2x taxable accounts

I also have an RRSP account through work. Every year I have been moving my contribution portion to my self-directed RRSP at Questrade. I can’t touch my employer’s contribution portion until I leave the company.

Neither Mrs. T nor I have work pensions so that may make the math slightly simpler.

The only complication I need to consider is what to do with income from this blog. This blog now makes a small amount of money. For tax efficiency, it might make sense to consider incorporating. Many bloggers I know have gone down this route for tax efficiency reasons. This is something I will have to consult with a tax specialist in the near future and crunch out some numbers to see what makes the most sense.

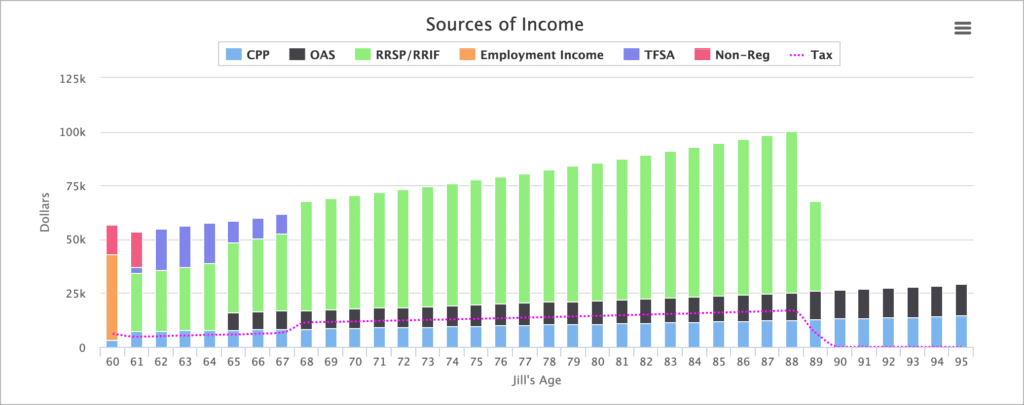

As the name suggests, the RRSP is a great retirement savings vehicle. But there are three important caveats people often skim over:

- RRSPs must be matured by December 31 of the year you turn 71. You can convert an RRSP into a RRIF or purchase an annuity. Most people convert their RRPs into RRIFs.

- A RRIF has a mandatory minimum withdrawal rate each year.

- The minimum withdrawal rate increases each year (5.4% at age 72 and jumps to 6.82% at age 80).

- RRSP and RRIF withdrawals are counted as normal income and taxed at your marginal tax rate.

Personally, I don’t like the restrictive nature of the RRIF. Imagine having $500,000 in your RRIF and having to withdraw a minimum of $27,000 at 72. If your RRSP/RRIF has a bigger value, it means you are forced to make a bigger withdrawal!

By plugging the amount currently in our RRSPs into a simple RRSP compound calculator, assuming no more contributions and an annualized return of 7%, I discovered that we’d end up with more than $2M in each of our RRSP!

Holy moly!

At 5.4% minimum withdrawal rate, that means we’d have to withdraw at least $108,0000 each. This would then put both of us into the third federal tax bracket. More importantly, we’d get hit with OAS clawback (more on that shortly).

Therefore, it makes sense for Mrs. T and me to consider early RRSP withdrawals and perhaps consider collapsing our RRSP before we turn 71.

CPP Clawbacks

Contrary to many Canadian beliefs, there are no clawbacks for CPP.

You pay into the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) with your paycheques. Each year that you contribute to the CPP will increase your retirement income. Therefore, the amount of CPP you will receive at 65 depends on your contributions during your working life.

In 2021, the maximum CPP benefit at age 65 is $14,445.00 annually or $1203.75 monthly. The CPP benefit is taxed at your marginal tax rate.

But not everyone will get the maximum CPP amount since it is based on how long and how much you pay into the CPP.

- You must contribute to CPP for at least 83% of the CPP eligible contribution time to get the maximum benefit. You are eligible to contribute to CPP from 18 to 65, so 83% would mean you need to contribute to CPP for at least 39 years.

- In addition, you also need to contribute CPP’s yearly maximum pensionable earnings (YMPE) for 39 years to qualify for the maximum CPP amount. For 2021, the YMPE is $61,600.

Not many people can meet these two requirements, hence the average CPP payment received in 2020 was $689.17 per month or $8,270.04 annually.

Since we plan to “retire early” eventually, it’s unlikely that we will qualify for the maximum CPP benefits.

OAS Clawbacks

Unlike the CPP, there are clawbacks or a pension recovery tax for OAS. If your income is over a certain level, the OAS payments are reduced by 15% for every dollar of net income above the threshold. In 2021, the OAS clawback threshold starts at $79,845 and maxes at $129,260. So, if you’re making over $79,845, you will receive reduced OAS payments. And if you’re lucky enough to have a retirement income of over $129,260, you get $0 OAS payments. Continue Reading…