By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

In response to rapidly accelerating inflation, central banks began raising rates aggressively at the beginning of 2022. Ever since, wild swings in bond markets have had a tremendous impact on virtually every single asset class.

This month, I examine the recent spike in rates from a historical perspective. Importantly, I will discuss the likely range of interest rates over the foreseeable future and the associated implications for financial markets.

When the Fed and other central banks were confronted with financial disaster in late 2008, they slashed interest rates to zero and deployed additional stimulative measures to ward off what many thought could be another Great Depression. Global rates then remained at levels that were both well below historical averages and the rate of inflation for the next 13 years.

In 2008, the runaway inflation of the 1980s and the painful medicine of record high rates that were required to subdue it were still relatively fresh in people’s minds. At that time, had you asked anyone what would be the most likely result of keeping rates near zero for over a decade, their most likely response would have been runaway inflation. And yet, inflation remained strangely subdued. According to most experts, this unexpected result is largely attributable to a relatively benign geopolitical climate and a related push toward global outsourcing.

This led to the notion of a “new normal” in which inflation was permanently expunged. Over the span of only 13 years, people went from fearing inflation to believing that it was a relic of the past unworthy of serious consideration. This false sense of comfort caused central banks and investors alike to be caught off guard in late 2021 when they realized that inflation had not been permanently vanquished but was merely hibernating.

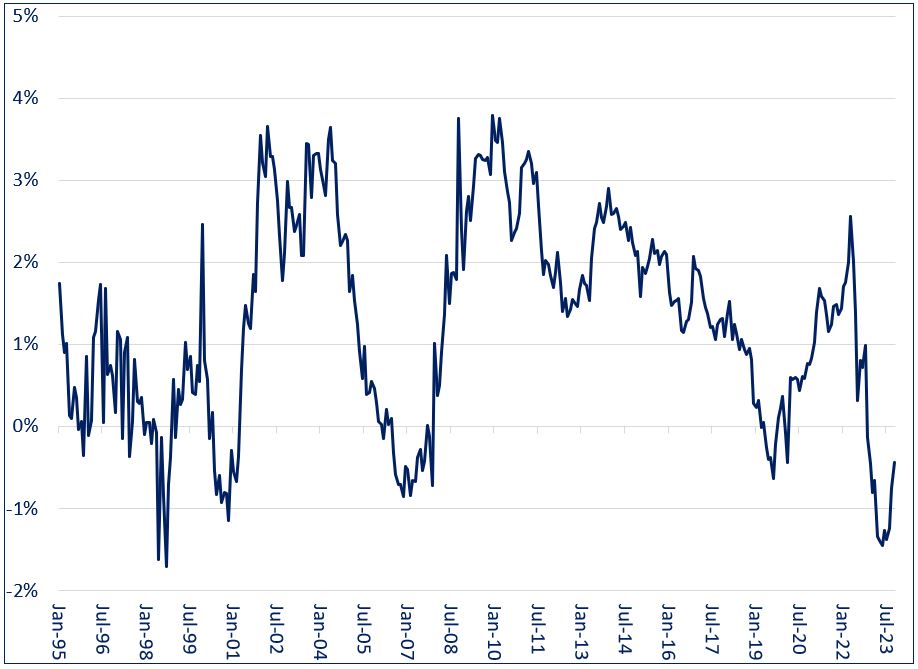

These sentiments were evident in bond markets. After rates were slashed to zero during the global financial crisis, investors were skeptical that they would remain there for long before stoking inflation. Longer-term rates remained well above their short-term counterparts, with the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries retaining an average 1.9% premium above the Fed Funds rate from 2009 – 2020.

However, 13 years of ultra-low rates with no sign of inflation allayed such fears, with the yield spread crossing into negative territory late last year and reaching a low of -1.5% in May of 2023. Even the rapid acceleration in inflation in late 2021 failed to fully disavow investors of the notion that the era of low inflation had come to an end, with current 10-year rates falling below their overnight counterparts.

10 U.S. Treasury Yield Minus Fed Funds Rate (1995 – Present)

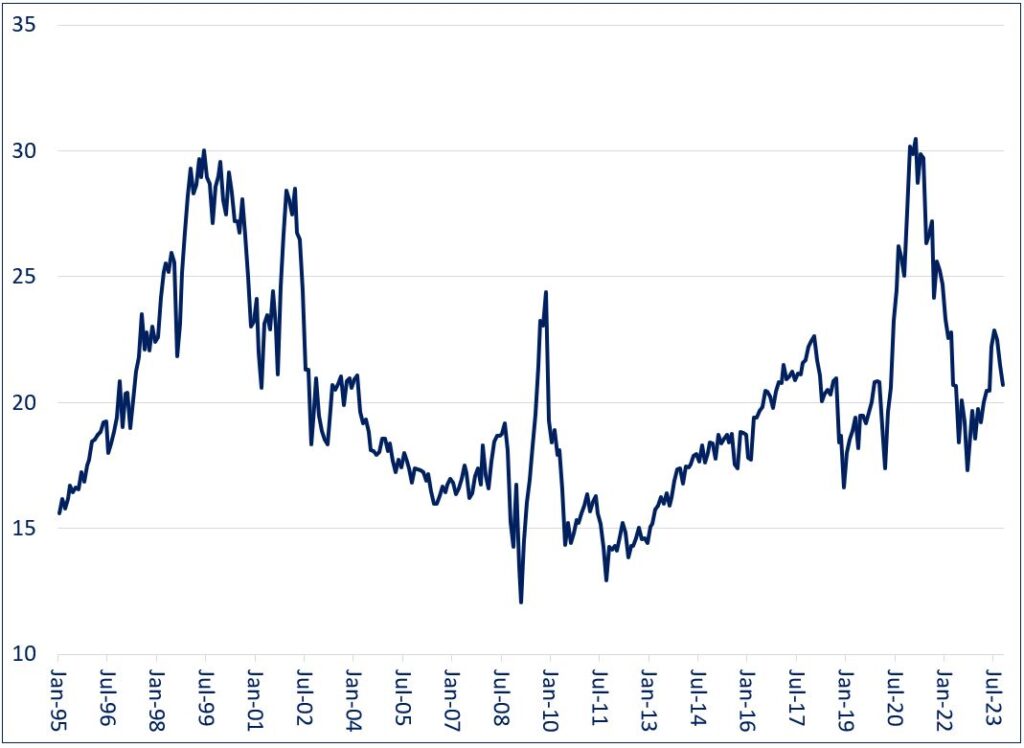

Equity markets danced to the same tune as their bond counterparts. When central banks cut interest rates to zero during the global financial crisis, investors were dubious that inflation would not soon rear its ugly head. Multiples remained relatively normal, with the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 Index averaging 16.4 for the five years beginning in 2009.

Over the ensuing several years, investors became complacent that the world would never again experience inflation issues, with the S&P 500’s P/E ratio climbing as high as 30 by early 2021. Multiples have since remained somewhat elevated by historical standards, indicating that markets have not fully embraced the fact that inflation may not be as well-behaved as what they are used to.

S&P 500 P/E Ratio (1995 – Present)

The Rising Tide of Declining Rates: Not to be Underestimated

According to legendary investor Marty Zweig:

“In the stock market, as with horse racing, money makes the mare go. Monetary conditions exert an enormous influence on stock prices. Indeed, the monetary climate – primarily the trend in interest rates and Federal Reserve policy – is the dominant factor in determining the stock market’s major direction.”

The 2,000-basis point decline in interest rates from 1980 to 2020 not only turbocharged aggregate demand (and by extension corporate revenues), but also dramatically lowered companies’ cost of capital. In tandem, these two developments were nothing short of a miracle for corporate profits and asset prices. Continue Reading…