Darling, I don’t know

Why I go to extremes

Too high or too low

There ain’t no in-betweens

And if I stand or I fall

It’s all or nothing at all

Darling, I don’t know

Why I go to extremes

- I Go to Extremes, by Billy Joel

By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

The stock market crash of 1929, which was followed by the Great Depression, was arguably the best thing to happen to investors in the history of modern markets.

I am in no way suggesting that investors took pleasure in having their life savings largely obliterated, nor am I implying that bear markets are enjoyable. However, the tremendous pain that people experienced left them with a deep distrust of stocks that lasted for decades. It was this wariness that kept valuations in check, thereby paving the way for strong returns.

Both the passage of time and rising markets eventually led investors to relinquish their pessimism. Eventually, acceptance morphed into adulation, the widespread view that stocks harbored no risk, and an “it can only go up” mindset that culminated in the late 1990s tech bubble. This excessive optimism caused valuations to become untethered from reality, with the S&P 500 Index reaching its highest valuation in history and huge market capitalizations being awarded to companies with little or no earnings.

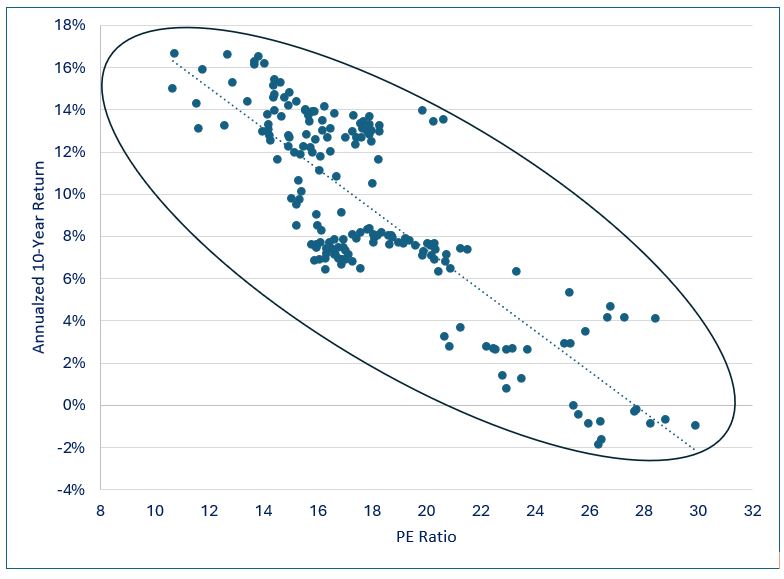

The irrational enthusiasm which created and propelled one of the greatest bubbles in modern history also set the stage for its ultimate demise in the form of a painfully long and deep bear market. Over shorter periods, fear can result in missed opportunities and regret while greed may get rewarded. However, over the long term, starting points of excessive pessimism set the stage for healthy markets while starting points of excessive optimism pave the way for disappointment. This observation is captured in the following graph, which clearly demonstrates that higher starting valuations lead to lower returns, and vice versa.

S&P 500 Index: PE Ratio vs. 10-Year Annualized Returns

This relationship brings to mind the following guiding principles of legendary investor Howard Marks:

- It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay that counts.

- Good investing doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.

- There’s no asset so good that it can’t become overpriced and thus dangerous, and there are few assets that are so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain.

- The riskiest thing in the world is the belief that there’s no risk.

Forget Forecasting: Context is Everything

I know that booms, recessions, bull markets, and bear markets have happened and that they will happen. Where I run into trouble is knowing when they will happen. I am in good company when it comes to this deficiency, as economic forecasting has by and large proven to be an exercise in futility. As famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith stated, “The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable”.

Given that predicting when changes in economic conditions will occur is a fool’s errand, investors should instead concern themselves with how markets will react if they occur. Importantly the same change can have a vastly different effect on markets depending on where valuations stand. Specifically, stock market multiples can be a gauge of the extent to which prices will decline in reaction to an adverse shift in the economic backdrop. Continue Reading…