By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

As I have written in the past, valuations are of no use for determining broad market returns over the short term.

To be clear, I am NOT implying that valuation doesn’t matter. Historical experience demonstrates that it has been an extremely powerful predictor of average returns over the long term. Without fail, whenever valuations have stood well below average levels, strong returns ensued over the next 7-10 years. Conversely, highly elevated valuations have preceded anemic or negative returns.

For investors interested in shorter-term market movements, sentiment indicators may harbor greater potential than their macroeconomic or valuation-based counterparts. In this month’s missive, I explore some of the more commonly cited indicators that purportedly possess short-term predictive capabilities to ascertain:

(1) Whether the historical record confirms the presence of any predictive power, and

(2) What these variables are signaling for markets in the near term.

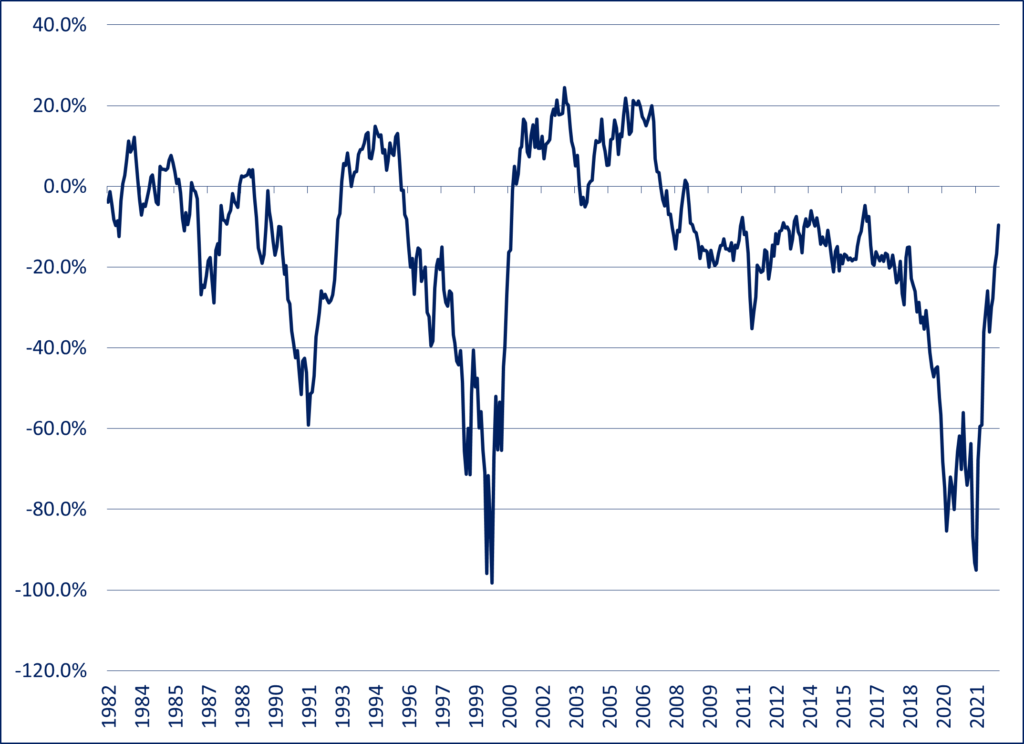

The VIX Index: Embrace the Fear

The VIX Index represents the market’s expectations of the S&P 500 Index’s volatility over the next 30 days. Its level is derived from the prices of S&P 500 options with near-term expiration dates. Dubbed the “fear index,” the VIX is often used to gauge market sentiment, and in particular the degree of fear among market participants.

Historically, the VIX has served as a good, if imperfect indicator of market turning points:

- Although it failed to provide a clear “get out of dodge” signal before the peak of the tech bubble in early 2000, the VIX’s historically stratospheric level in late 2002 indicated a level of extreme fear that signaled that better times were at hand.

- In early 2007, the VIX stood at very depressed levels, indicating the high degree of complacency that contributed to the global financial crisis of 2008. Unfortunately, it was far too early in signaling the recovery. In October 2008, extremely elevated VIX levels were signaling the type of abundance of fear that often precedes rebounds, yet stocks still had plenty of downside before ultimately bottoming in March of 2009.

- More recently, the VIX failed to provide a warning signal of the market turmoil of 2022. However, its extremely elevated stance in late October of 2022 signaled that a rebound was imminent.

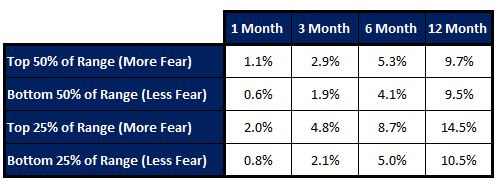

VIX Index Levels and S&P 500 Index Returns: 1997 – Present

Putting specific bear markets and recoveries aside, the above table demonstrates that elevated VIX/fear levels have on average preceded higher returns, and depressed VIX/lower fear levels have foreshadowed lower returns. The historical record lends credence to Buffett’s sage advice that it is wise for investors to be “fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.”

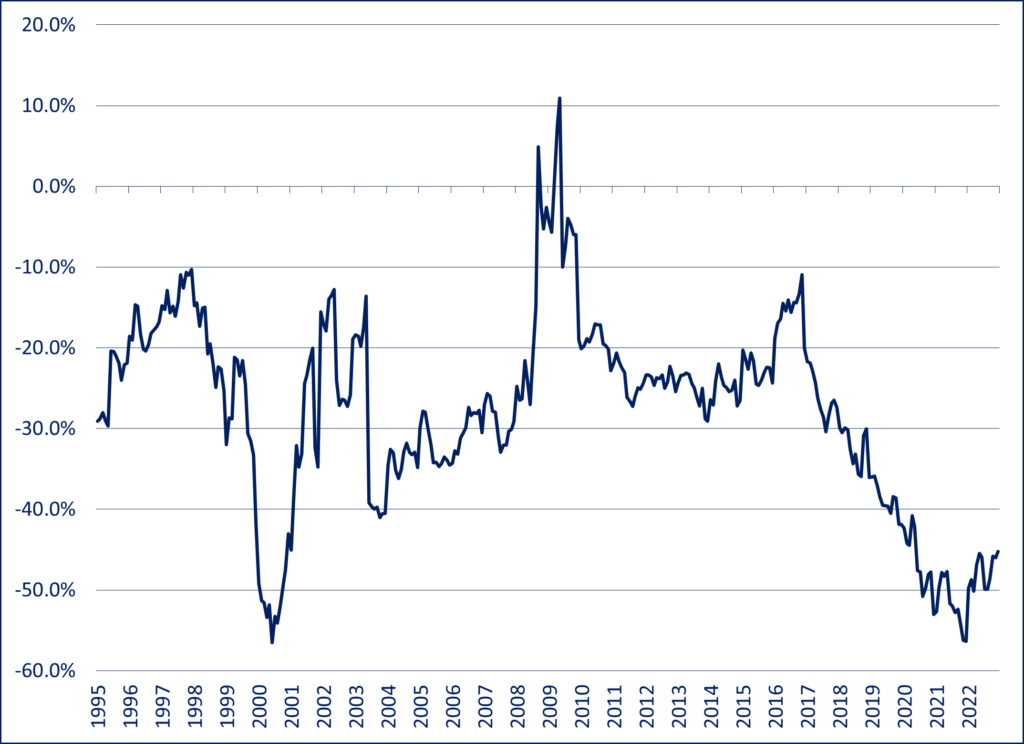

Put Call Ratio: Beware Cheap Insurance

Like the VIX Index, the put-call ratio (PCR) is widely used to gauge the overall mood of the market. Put options provide the right to sell stocks at a predetermined price and are often purchased as insurance to protect portfolios from market declines. Call options offer the right to buy stocks at a predetermined price and are frequently bought to capture upside participation when stock prices rise.

The PCR increases when the market participants’ desire for downside protection rises relative to their desire for upside participation. Alternately stated, a rise in the PCR is indicative of a rise in bearish sentiment. Conversely, the PCR falls when people become more focused on reaping gains than on avoiding losses, which is indicative of a rise in bullish sentiment.

Since 1997, the PCR has been a contrarian indicator, whereby elevated levels (high fear/low greed) have on average signaled higher returns and lower PCRs (low fear/high greed) have heralded subdued or negative results. Continue Reading…