It’s not hard to find a report about the growing Canadian debt problem. Canadians owe $1.77 for every $1 they make. The average consumer owes $31,400 in installment and auto loans, while borrowing for credit cards and lines of credit average $18,500 per consumer. Finally, there are reports that nearly half of Canadians won’t be able to cover basic living expenses without taking on new debt.

Half of Canadians say they have less than $200 left over at the end of the month, after household bills and debt payments. Canadians’ household savings rate is an abysmal 1.7 per cent.

Canadians have a major debt problem! All the warning signs are there. We’re overextended, borrowing to maintain our cost of living, and at risk of insolvency if a recession hits. It’s a crisis!

Our affordability problem

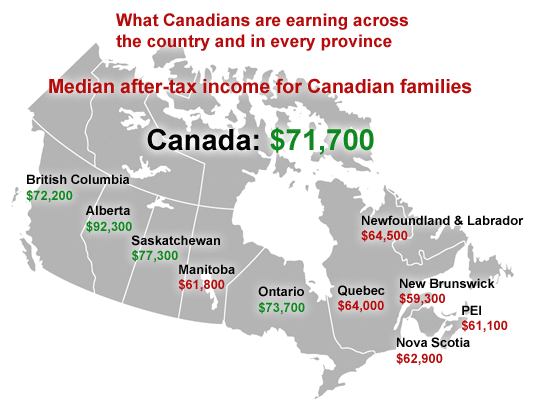

Not so fast. It looks to me like Canadians have an income problem, not a debt problem. Or, put a different way, Canadians have an affordability problem. The median after-tax income for Canadian families is $71,700. Meanwhile, the average house price in Canada is $512,501. That’s an incredible 7x income! For reference, the typical rule of thumb for housing affordability is 2.5x income. That means Canadians should be buying homes worth $179,250.

The discrepancy is even more staggering in B.C. and Ontario:

| Avg. house price | Median income | Affordability | |

| British Columbia | $696,115 | $72,200 | 9.64x |

| Ontario | $618,165 | $73,700 | 8.39x |

It’s not just housing. Child care costs have risen faster than inflation in nearly two-thirds of cities since 2017. It’s often the single largest household expense after rent or a mortgage. The median cost of child care in Canada’s largest cities hovers around $1,000 per month, with parents in Toronto paying $1,675 per month. The exception is in Quebec, where a universal child care program has been in place for more than two decades (families pay $175 per month for child care in Montreal).

Transportation is the next largest expense for Canadians. On average, we owe $20,000 on our vehicles. The average price of a new vehicle has risen to $37,577. Today, it’s common to see auto loans stretched out over seven or eight years. That helps lower monthly payments slightly, but families are easily paying $500 per month or more on each vehicle (with many two-car families).

Beyond frivolous Debt

All this to say, it’s no wonder Canadians are struggling to get by from month-to-month. We’re accessing cheap credit, in a lot of cases, to fund basic living expenses or cover emergencies. It’s not like we’re out there buying diamonds and furs.

Furthermore, Scott Terrio, insolvency expert at Hoyes Michalos, says it can be misleading to suggest Canadians are so close to insolvency. He says there is a lot of runway between when someone is in financial trouble and when they file a legal insolvency.

“One can be technically insolvent for months, even years, before they need to consider an actual filing. We regularly have clients tell us that they should have come in to see us 12-24 months earlier than they did. That’s because there are all sorts of ways to stave off a legal insolvency.”

Indeed, there are only about 55,000 bankruptcies and 75,000 consumer proposals filed by Canadians every year.

“And there are 37 million Canadians, so you do the math,” says Terrio.

It’s an Income problem

No, we have an income problem that is crippling our ability to save. I’ve seen it firsthand. As a young homeowner, who admittedly got in over his head as a first time buyer, I struggled to pay my mortgage, buy groceries, and service my student loan debt (another issue altogether for young Canadians).

I had a roommate kick in $400 per month for a while, but when he moved out things went downhill in a hurry. I started using my credit card to cover basic living expenses, but got into real trouble when I maxed that out and had nowhere to turn.

While I did take out a consolidation loan to help manage my debt, the real savior was when I got a promotion at work that came with a $12,000/year salary increase. That extra income gave me the ability to make my consolidation loan payments on time, not have to dip back into credit, and start establishing a savings plan.

Earning extra income, either through a promotion, career change, or side hustle, has been part of my financial success ever since. Without it, I might still be stuck in a debt spiral: living paycheque-to-paycheque with no path to financial freedom.

But not everyone has the ability to earn extra income. Wage growth is barely keeping up with inflation and hasn’t for many years since the global financial crisis. Salaries have been frozen in many industries, especially in the public sector. It’s tough to get ahead when you can’t even count on an annual cost of living adjustment.

Side hustles require time and skill that not everyone has. So we’re left to cut costs at the margins and hope that our pets don’t get sick, our furnace survives another winter, and our tires can last another year. There’s no room for error.

Final thoughts

Reports about our growing debt-to-income ratio and consumer credit are concerning, but should be taken with a grain of salt. As Terrio says, half of Canadians are not on the brink of insolvency. The vast majority of us faithfully repay our mortgages and consider selling our house a last resort (but it is an option).

Personally, I have a higher than average debt-to-income ratio, simply because I still owe $200,000 on my mortgage. And I don’t have much money left over at the end of the month because I try to optimize my finances so that every dollar of income is allocated towards “something” rather than just sitting in my chequing account.

It’s easy to wag our fingers at indebted Canadians and suggest they quit buying lattes and avocado toast. But in many cases it’s not frivolous expenditures that are getting Canadians into trouble. It’s regular, day-to-day living expenses.

Trimming expenses won’t solve these inherent issues. They require major life decisions, such as taking on a second job, going back to school, moving away from a major city to a more affordable area, paying large child care costs for many years to ensure both parents can stay in the workforce, or getting by on one vehicle instead of two. Not easy decisions.

In addition to running the Boomer & Echo website, Robb Engen is a fee-only financial planner. This article originally ran on his site on Nov. 6, 2019 and is republished here with his permission.

In addition to running the Boomer & Echo website, Robb Engen is a fee-only financial planner. This article originally ran on his site on Nov. 6, 2019 and is republished here with his permission.