Dedicated readers will know I’m on a mission with this strategy – an aggressive one at that – to hopefully earn $30,000 per year in dividend income from a few key accounts.

I figure this income stream, supplemented with other assets (e.g., RRSPs, workplace pensions, other), should set us up well for semi-retirement in the coming years.

While I love dividends, especially from my Canadian stocks, I invest beyond Canada’s borders using some low-cost U.S.-listed ETFs.

You can find some of my favourite ETFs to own here.

I invest this way (more than ever) since I believe in portfolio diversification. In using some low-cost U.S. ETFs, I obtain this diversification and therefore opportunities for long-term growth at a very low cost.

This makes me a ‘hybrid’ investor: using a basket of Canadian (and some U.S.) dividend growth stocks for passive, rising income and using some low-cost ETFs to ride the general stock market equity returns. I believe in this two-pronged approach since it should not only provide some passive income for life, but it should also deliver capital appreciation as well.

Like other Canadian bloggers that I look up to, I’ve been building my dividend stock portfolio (and adding to it) since around 2008-2009. I’m well on my way to earning the desired $30,000 per year from a few accounts: a recent update you can find here.

Should you follow this approach?

Is hybrid investing right for you?

Well, check out the rest of this post and you can decide …

Your Ever Growing Income

My friend and past contributor to this site, Henry Mah, recently released a book called Your Ever Growing Income.

You can read about the Canadian and U.S. versions of that book here.

Henry recent encouraged bloggers and passionate investors like myself to publish some answers to a few questions: about income investing and my retirement strategy.

Today’s post does just that!

Income Investing and my Retirement Strategy

1.) What stocks should you buy and why?

I have a bias to owning companies that have a long, established history of rewarding shareholders.

You can see some of the very dividend-friendly histories of many Canadian stocks here.

On my Dividends page, I have highlighted some of the stocks I own; they are:

- Canadian banks (examples: RY, TD, BNS, BMO, CM).

- Canadian insurance companies (examples: SLF, MFC, GWO).

- Canadian pipeline companies (examples: ENB, TRP, IPL).

- Canadian telecommunications companies (examples: BCE, T).

- A few major Canadian energy companies (like SU).

- Canadian utilities (examples: FTS, EMA, AQN, CU, CPX, INE, BEP.UN).

My thinking?

Basically, I buy companies that people need. People need to bank, so I own banks. People need insurance, so I own insurance companies. Last time I checked people want to heat and cool their home(s) in Canada, so I own those companies too. I think you get the idea …

I also own a number of Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Examples include REI.UN, HR.UN, CAR.UN, CHP.UN and a few more. I’ve basically unbundled REIT ETFs like ZRE, XRE and ZRE to own those companies directly.

I tend to own what the big funds in Canada own. I don’t pay any money management fee to do so. [See holdings of the iShares i60s shown at the top of this blog.]

2.) How do I evaluate the merits of the stocks I am considering?

My approach is rather simple:

- If the Canadian company pays a dividend, I might consider it.

- If the Canadian company has paid a dividend for many years, I will consider it.

- If the company has paid a dividend for decades or generations, I will most undoubtedly want to own it.

- If the company has raised its dividend for decades or generations, I probably already own it.

As part of my portfolio, I also consider the following when buying and holding stocks:

- Sector diversification: given Canada is dominated by financial and energy sectors, I try to invest in healthcare, consumer stocks and technology companies state-side via low-cost U.S. ETFs.

- Earnings: I look at company earnings for any longer-term warning signs.

- Payout ratio: I look at the company’s dividend payout ratio for any flags.

- High yield: I try to avoid chasing yield since I believe consistent dividend growth and increases (ideally year-after-year) are some keys to wealth creation; not owning a high-yield stock whereby the dividends are likely unsustainable

3.) When should you invest more money into new stocks or the ones you already own?

Tough question!

I can’t predict the future … although I wish I could.

For the most part, I don’t deviate very far from the existing ~30 Canadians stocks I own. I tend to buy more shares in the stocks I own when they’ve been beaten up. If people have a hate-on for banks, I buy them. If REITs have been punished of late, I buy those. You get the idea. I hope to rinse and repeat this approach until wealthy.

That means, I’ve essentially unbundled the top-Canadian ETFs like XIU, XIC, VCN and a few others for passive income.

Maybe you shouldn’t take my word for it. Here is some very sage advice:

“The selection of common stocks for the portfolio of the defensive investor should be a relatively simple matter. Here we would suggest four rules to be followed:

- There should be adequate thought not excessive diversification. This might mean a minimum of ten different issues and a maximum of about thirty.

- Each company should have a long record of continuous dividend payments …

- Each company selected should be large, prominent, and conservatively financed …

- The investor should impose some limit on the price he will pay for an issue in relation to its average earnings over, say the past seven years.” – Benjamin Graham, considered the father of value investing; most well-known disciple of his teaching: Warren Buffett.

4.) When should you sell your stocks?

Hardly ever.

I mean it.

As long as the dividends are paid and continue to increase year-after-year, I will own the stocks I do: the banks, the utilities, the pipelines, the telcos, and so on,

That said, no company nor investing approach is perfect so if the company you own stopped increasing its dividends for a few years, it might be time (depending upon the broader economic climate) to ditch the company.

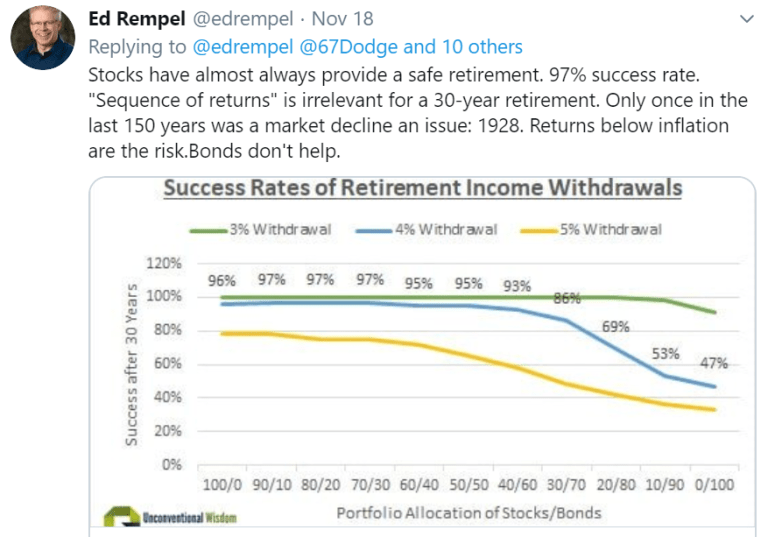

5.) Should you be worried when the market and prices are going down? Why?

No.

I mean that too.

Why?

Consider stock prices going down like a sale.

Investing in the stock market seems like the only place in the world where people don’t celebrate paying less for something they want to buy.

If your intention, like mine, is to own a basket of dividend paying stocks that have a long track record of rewarding shareholders with raises, then you should really learn to train your investing brain and look at broad market declines as a great way to celebrate buying stocks on sale.

Here’s how to prepare for any market meltdown. Continue Reading…