By Anita Bruinsma, CFA

By Anita Bruinsma, CFA

Clarity Personal Finance

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

Getting an income from dividends is a concept that is often mentioned in the personal finance world. It can seem like an elusive concept – a unicorn – or perhaps something for the super-rich or those with investment gurus at their disposal. In reality, though, anyone with some savings can earn dividends and it doesn’t require much expertise.

A dividend is a cash payment made by a company to its shareholders. Shareholders are simply people who own stock (or shares) in their company. If I own shares of TD Bank, I get $3.56 per year for every share I own. It might not sound like much, but if I invest $3,000 in TD Bank today, I’d be in line to get $132 over a year. It adds up!

Let’s get something straight though: living entirely off dividends requires a lot of money available to invest. It’s not a reality for most people.

Here are a few numbers to give you context. In order to earn $40,000 a year (before tax) from dividends, you’ll need a portfolio of about a million dollars to invest in stocks.* You’ll then have to pay tax on these dividends (except for those that are earned within your TFSA). As you can see, living off dividends isn’t a strategy available to most people.

If you are looking to supplement your income to maybe pay for your annual vacation, you can earn $5,000 a year (all figures are before tax) with $125,000 to invest. For $10,000 a year, you’ll need about $250,000.

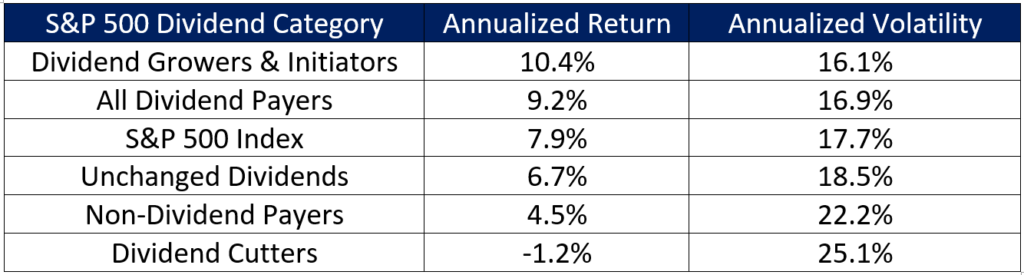

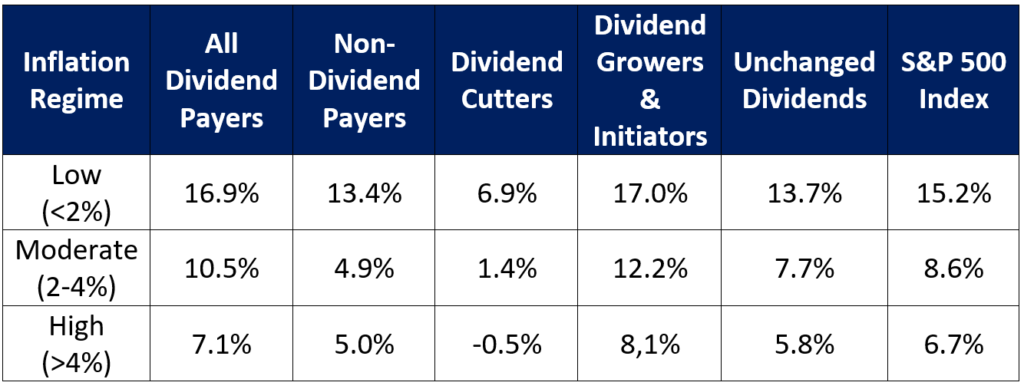

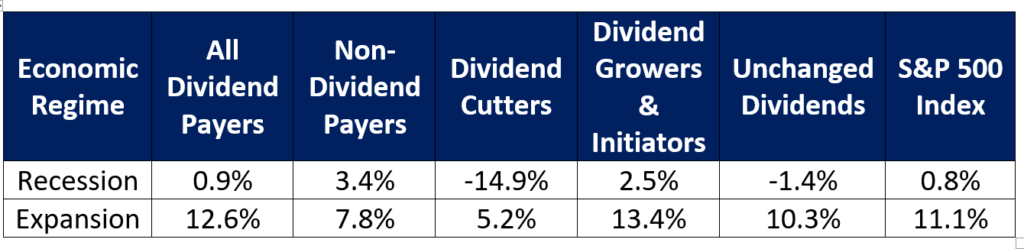

Dividends have more benefits that just giving you cash flow – they also give you a reasonably reliable investment return and can protect against inflation. A company that has a long history of paying a dividend and consistently growing it over time provides a quasi-guaranteed return on a stock. (No dividend is guaranteed but it can be consistent and dependable.) Even though the stock prices goes up and down (unreliable), you’ll get the dividend (reliable). Even better, many companies increase their dividend year after year, sometimes at a rate higher than inflation, so dividends can help protect you from the ravages of inflation too. You can read more about dividends in a prior blog post.

DRIPs

For those who don’t need the additional cash flow, another way of benefitting from dividends is to reinvest them. There are two ways to receive a dividend: it can be paid in cash into your account or it can be paid to you in shares. This is called a Dividend Reinvestment Plan, or DRIP. If you sign up for a DRIP, you’ll receive additional shares of the company you are invested in. For example, if you own BCE (Bell), and you own 100 shares, you’ll be entitled to a dividend payment of $368 every year. You could get that in cash, or you could get 6 more shares of BCE. This is great because then next year you’ll get a dividend on 106 shares – and the snowball keeps rolling.

There is important roadblock to this strategy for a lot of people: if you want to earn dividends, you have to invest the cash in dividend-paying stocks or funds. This means that if all of your savings amounts to $125,000, and you want to earn $5,000 in dividends, you will need to invest all of it and you will not be well-diversified nor will you have any money in less volatile investments like bonds or GICs. You also need to ensure you have enough money that isn’t invested in the market to use in emergencies or for near-term uses.

Dividend ETFs

If you’ve decided that you want income from dividends and you’re comfortable with having your savings invested in the market, you might asking “Now what?” How do you get these dividends flowing? Well, you’ll need to find investments that pay dividends, preferably reliable, consistent, high, and growing ones. Unless you have a large portfolio, the most efficient and the simplest way to invest for dividends it to put your money in a high dividend-paying exchange traded fund. This kind of ETF will invest in companies that pay high dividends and as an investor, this money will flow through to you via fund distributions, which you can choose to take as cash or re-invest in more units of the fund (like a DRIP).

To find an appropriate ETF, do a Google search for “high dividend yielding ETFs” and drill down into a few. There are three things to look at when choosing which to invest in:

- What is the yield? Higher is better.

- Does it invest in a broad swath of the stock market? Avoid ones that invest in a specific sector.

- What is the MER, or annual fee? The fees on these ETFs are higher than broad market ETFs but you can find a high yielding ETF for less than 0.20% per year.

Yield is the most relevant number to look at with dividend investing. It’s simply a measure of how much income you will get as a percent of the amount you invest. It’s like an interest rate on a GIC: if a GIC pays 4% interest, you get $40 for every $1,000 you invest. If a stock has a dividend yield of 4% you’ll get $40 of dividends for every $1,000 you invest. (Dividends don’t happen in nice round numbers like that, though.) If an ETF has a 4% yield, you’ll get $40 in distributions from the fund.

Although I am not usually a proponent of stock picking, this is one situation where I feel that owning individual, high-dividend paying stocks can be okay. If you have enough money to own a number of stocks, you could put together a portfolio of high-quality dividend stocks that have a long track record of paying and growing their dividends. In Canada, this list would probably include Canadian banks, telecom companies and utilities, among others. For example, a portfolio consisting of TD Bank, Royal Bank, Manulife, BCE, Telus, Enbridge, Fortis and Algonquin Power yields more than 5% right now.

Are you still with me? If that last paragraph made you want to stop reading, please don’t! If you’re not into investing in individual stocks, keep it simple and go the ETF route. Here are a few Canadian ones to look at:

iShares S&P/TSX Composite High Dividend ETF (XEI)

Vanguard FTSE Canadian High Dividend Yield Index (VDY)

BMO Canadian Dividend ETF (ZDV)

(Note: You can also buy U.S. and international dividend ETFs.)

The yields on these ETFs and on dividend-paying stocks are quite high right now. This is because the stock market has fallen. As the price of a stock falls, the dividend yield increases because you need to spend less per share to get the same dividend. To demonstrate, let’s look at BCE (Bell). BCE pays a dividend of $3.68 per year. If the stock is trading at $63 (as it was a year ago) you pay $63 to get a $3.68 dividend, which is a 5.8% yield ($3.68/$63). Today, BCE is trading at $57 which means it has a yield of 6.5% ($3.68/$57). (If you are ticked off at the amount of your internet, cable and cell phone bill with Bell, offset it with some sweet dividends!)

Living off dividends? Probably a pipe dream. Adding some cash flow, getting a good return on your investment, and fighting inflation? Not a unicorn – it’s totally doable!

*Assumes a 4% dividend yield.

Anita Bruinsma, CFA, has 25 years of experience in the financial industry. As a long-time investor, Anita is passionate about demystifying investing to make is accessible to more people. After a long and satisfying career in the world of banking and wealth management, including 15 years managing mutual funds with a Canadian bank, Anita started Clarity Personal Finance, and now helps people learn to better manage their finances, including how to invest for themselves.

Anita Bruinsma, CFA, has 25 years of experience in the financial industry. As a long-time investor, Anita is passionate about demystifying investing to make is accessible to more people. After a long and satisfying career in the world of banking and wealth management, including 15 years managing mutual funds with a Canadian bank, Anita started Clarity Personal Finance, and now helps people learn to better manage their finances, including how to invest for themselves.

Good Canadian stocks of blue chip companies can give investors an additional measure of safety in volatile markets. And the best ones offer an attractive combination of moderate p/e’s (the ratio of a stock’s price to its per-share earnings), steady or rising dividend yields (annual dividend divided by the share price) and promising growth prospects.

Good Canadian stocks of blue chip companies can give investors an additional measure of safety in volatile markets. And the best ones offer an attractive combination of moderate p/e’s (the ratio of a stock’s price to its per-share earnings), steady or rising dividend yields (annual dividend divided by the share price) and promising growth prospects.