By Michael J. Wiener

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

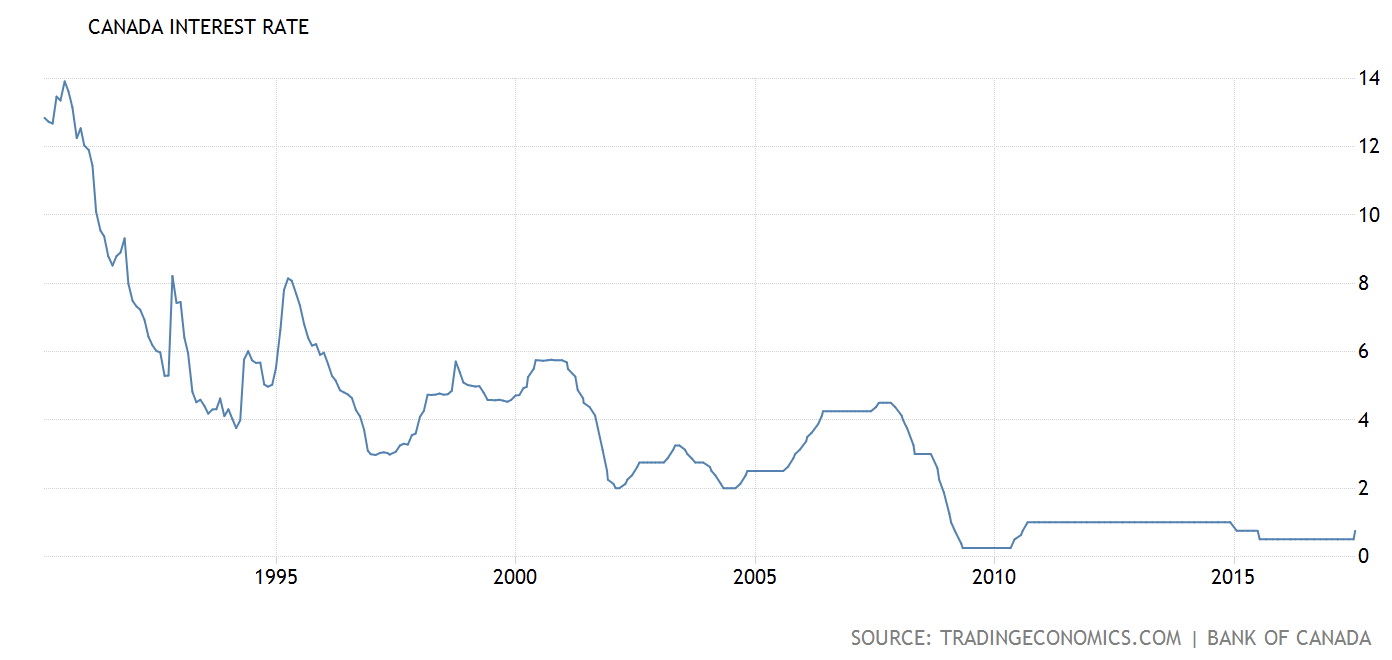

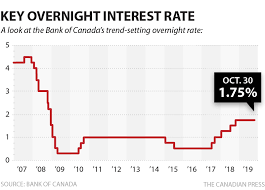

Today’s long-term bonds pay such low interest rates that it makes no sense to own them. There is virtually no upside, and rising interest rates loom on the downside. Warren Buffett called this “return-free risk.” He was right. Here I explain the problem and address objections.

As I write this, 10-year Canadian government bonds pay 0.623% interest. If you invest $10,000, you’ll get a total of only $623 in interest over the decade, and then you’ll get your $10,000 back. This is crazy. Even if inflation stays at just 2%, you’ll lose $1237 in purchasing power.

Even worse are 30-year Canadian government bonds that pay 1.224% as I write this [late in October 2020.] Your $10,000 would get a total of $3672 in interest over 3 decades. This is a pitiful amount of interest over a full generation. At 2% inflation, you’ll lose $1738 in purchasing power. Even a portfolio that only beats inflation by 2% per year would gain $8113 in purchasing power over 30 years.

All investments have risk, but there has to be some potential upside to justify the risk. Where is the upside for long-term bonds? The only upside comes if we have sustained deflation. It’s crazy to risk so much just in case the prices of goods and services drop steadily for the next decade or three.

Some investors mistakenly think they can always sell bonds and collect accrued interest. That’s not how it works. With a 30-year bond, the government is promising to pay you the tiny interest payments and give you back your principal after 3 decades. If you want out, you have to sell your bond to someone else who will accept these terms. You don’t get accrued interest; you get whatever another investor is willing to pay. Counting on selling a bond is hoping for a greater fool to bail you out. If future investors demand higher interest rates on their bonds, your bond will sell at a significant capital loss.

If the interest rate on 30-year bonds goes up over time, that’s actually bad for current bond owners, because they have to live with their lower rate instead of receiving the new rate. If 30-year bond interest rates go up by 1%, you immediately lose 30 years of 1% interest; you can’t just sell to avoid the loss because other investors wouldn’t happily take these losses for you.

Let’s go through some objections to this argument against owning today’s long-term bonds:

1.) Stocks are risky

It’s true that stocks are risky, but I’m not suggesting that investors replace long-term bonds with stocks. Short-term bonds and high-interest saving accounts are safer alternatives. A decision to avoid long-term bonds doesn’t have to include a change in your asset allocation between stocks and bonds. For anyone willing to look beyond Canada’s big banks, it’s not hard to find high-interest savings accounts paying at least 1.5% and offering CDIC protection on deposits. If long-term bond interest rates ever return to historical norms, it’s easy to move cash from a savings account back into bonds. So, you don’t have to live with a measly 1.5% forever.

2.) Investors need to diversify

The benefit from diversifying comes from owning assets with similar expected returns that aren’t fully correlated. However, the expected returns of today’s bonds are dismal. We don’t really own bonds for diversification these days. The real reason we own bonds is to blunt the risk of stocks. It doesn’t make sense to try to reduce portfolio risk by buying risky long-term bonds. Flushing away part of your portfolio with long-term bonds isn’t a reasonable form of diversification. Short-term bonds and high-interest savings accounts do a fine job of reducing portfolio volatility without adding significant interest rate risk.

3.) Long-Term bonds have higher interest rates than short-term bonds

Historically, long-term bonds rates usually have been higher than short-term rates. Today, however, high-interest savings accounts pay more interest than long-term government bonds. But that’s not the only consideration. Interest rates will change over the next 30 years. If you own short-term bonds, your returns will change too. However, if you buy 30-year bonds, your interest rate won’t change for three decades. If interest rates rise, new short-term bond rates will be higher than your old 30-year rate. Continue Reading…