I’ve read a lot of bad takes on RRSP contributions and tax rates over the years. One that stands out is the argument that you should avoid RRSP contributions entirely, and focus instead on investing in your TFSA and (gasp) your non-registered account. This idea tends to come from wealthy retired folks who are upset that their minimum mandatory RRIF withdrawals lead to higher taxes and potential OAS clawbacks. They also seem to forget about the tax deduction generated from their RRSP contributions and the tax-sheltered growth they enjoyed for many years leading up to retirement.

I’m hoping to dispel the notion of an RRSP disadvantage by reframing the way we think about RRSP contributions, RRIF withdrawals, and tax rates. Here’s what I’m thinking:

Most reasonable RRSP versus TFSA comparisons say that it’s best for high income earners to prioritize their RRSP contributions first, while lower income earners should prioritize their TFSA contributions first.

The advantage goes to the RRSP when you can contribute at a higher marginal tax rate and then withdraw at a lower marginal tax rate, while the advantage goes to the TFSA when you contribute at a lower rate and withdraw (tax free) at a higher rate.

If your tax rate in your contribution years is the same as in your withdrawal years then there’s no advantage to prioritizing either account. They’re mirror images of each other.

Related: The next tax bracket myth

This comparison focuses on marginal tax rates. But is this the correct way to frame the discussion?

Marginal Tax Rate vs. Average Tax Rate

Isn’t it fair to say that an RRSP contribution always gives the contributor a tax deduction based on their top marginal tax rate (assuming the deduction is claimed that year)?

But when you look at retirement withdrawals, shouldn’t we focus on the average tax rate and not the marginal tax rate?

An example is Mr. Jones, an Alberta resident with a salary of $97,000 – giving him a marginal tax rate of 30.50% and an average tax rate of 23.59%

If Mr. Jones contributes $10,000 to his RRSP he will reduce his taxable income to $87,000 and get tax relief of $3,050 ($10,000 x 30.5%).

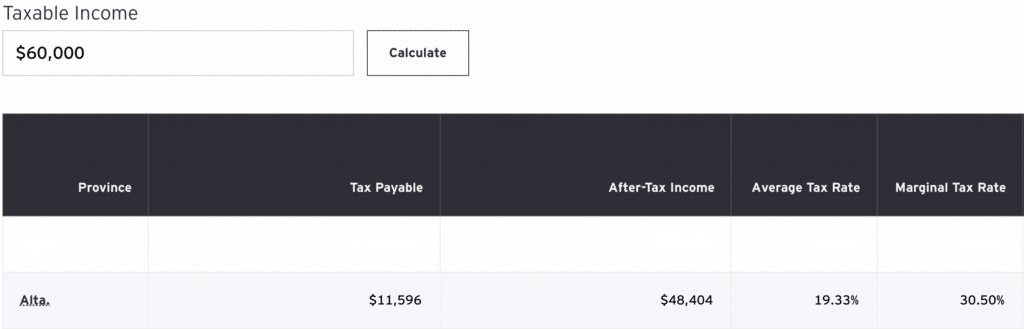

Fast forward to retirement, where Mr. Jones has taxable income of $60,000 from various income sources, including a defined benefit pension, CPP, OAS, and his $10,000 minimum mandatory RRIF withdrawal.

The range of income in each tax bracket can be quite broad. With $60,000 in taxable income, Mr. Jones is still at a 30.5% marginal tax rate, but his average tax rate is just 19.33%. That’s right, he pays just $11,596 in taxes for the year.

Conventional thinking about RRSPs and marginal tax rates would tell us that Mr. Jones should be indifferent about contributing to an RRSP in his working years because he’ll end up in the same marginal tax bracket in retirement.

But when we consider all of our retirement income sources, why do we treat the RRSP/RRIF withdrawals as the last dollars of income taken (at the top marginal rate) instead of, say, income from CPP or OAS or from a defined benefit pension? Why would Mr. Jones’ $10,000 RRIF withdrawal be taxed at 30.5% when it’s his average tax rate that matters? Continue Reading…