By Carol Lynde, Bridgehouse Asset Managers

By Carol Lynde, Bridgehouse Asset Managers

Special to Financial Independence Hub

If you Google “what contributes to positive mental health?,” you’ll find helpful tips on exercise, diet, getting enough sleep and mindfulness. You’ll find advice on connecting with people, building resilience, gaining control over your life and getting help from a mental health professional. You might find mention that reducing your debt and controlling spending can reduce stress. But you’ll find very little about financial planning or that making a financial plan can contribute to positive mental well-being.

It can.

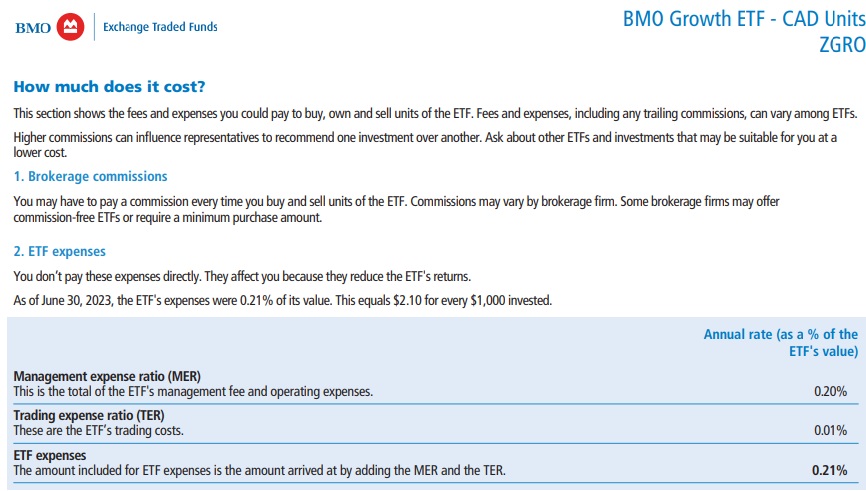

Bridgehouse Asset Managers recently released research confirming a direct link between planning your finances and positive mental well-being. The more financial planning activities you do, the better your sense of security, control, ability to bounce back from life’s challenges and positive mindset. Further, having a financial plan makes you less anxious about today’s financial issues, such as cost of living, debt levels and saving enough to retire.

The Bridgehouse national research project included focus groups and an online survey developed in partnership with the Canadian Mental Health Association (Toronto) and an advisory panel including mental health, legal and financial advisor experts from across the country. The research found that it’s not the amount of money you have, it’s doing something that counts. Planning your finances and creating a plan for the future leads to a sense of hope, security, resilience and control: all attributes associated with positive mental health.

There’s a compounding effect: the more financial planning you do, the better your mental health. The survey asked participants how many of 10 financial planning activities they had completed and compared the results to their self-assessed mental state.

The research concluded the more activities respondents completed, the better their sense of security, control, ability to bounce-back and positive mindset. Financial planning activities included: calculating retirement requirements, calculating net worth, determining short-term goals, determining long-term goals, determining insurance requirements, establishing an emergency fund, creating a debt management plan, creating a budget, actively finding day-to-day savings and scheduling regular meetings with a financial advisor.

Of respondents who did seven or more financial planning activities:

- 73 per cent expressed a sense of security about their financial situation.

- 73 per cent felt in control of their financial situation.

- 79 per cent felt an ability to bounce back if life throws tough challenges.

- 79 per cent reported a positive mindset.

Respondents who took even small steps claimed positive mental well-being benefits. Of those who did only one-to-three financial planning activities:

- 52 per cent reported a sense of security.

- 54 per cent reported a sense of control.

- 73 per cent felt an ability to bounce back.

- 71 per cent reported a positive mindset.

According to regression analysis (a research method to rank contribution weighting), establishing/maintaining an emergency fund and scheduling regular meetings with a financial advisor were the two most important drivers of positive mental well-being and the ability to sleep at night. Continue Reading…