Setting up the initial asset allocation for your investment portfolio is fairly straightforward. The challenge is knowing how and when to rebalance your portfolio. Stock and bond prices move up and down, and you periodically add new money – all of which can throw off your initial targets.

Setting up the initial asset allocation for your investment portfolio is fairly straightforward. The challenge is knowing how and when to rebalance your portfolio. Stock and bond prices move up and down, and you periodically add new money – all of which can throw off your initial targets.

Let’s say you’re an index investor like me and use one of the Canadian Couch Potato’s model portfolios – TD’s e-Series funds. An initial investment of $50,000 might have a target asset allocation that looks something like this:

| Fund | Value | Allocation | Change |

| Canadian Index | $12,500 | 25% | — |

| U.S. Index | $12,500 | 25% | — |

| International Index | $12,500 | 25% | — |

| Canadian Bond Index | $12,500 | 25% | — |

The key to maintaining this target asset mix is to periodically rebalance your portfolio. Why? Because your well-constructed portfolio will quickly get out of alignment as you add new money to your investments and as individual funds start to fluctuate with the movements of the market.

Indeed, different asset classes produce different returns over time, so naturally your portfolio’s asset allocation changes. At the end of one year, it wouldn’t be surprising to see your nice, clean four-fund portfolio look more like this:

| Fund | Value | Allocation | Change |

| Canadian Index | $11,680 | 21.5% | (6.6%) |

| U.S. Index | $15,625 | 28.9% | +25% |

| International Index | $14,187 | 26.2% | +13.5% |

| Canadian Bond Index | $12,725 | 23.4% | +1.8% |

Do you see how each of the funds has drifted away from its initial asset allocation? Now you need a rebalancing strategy to get your portfolio back into alignment.

Rebalance your portfolio by date or by threshold?

Some investors prefer to rebalance according to a calendar: making monthly, quarterly, or annual adjustments. Other investors prefer to rebalance whenever an investment exceeds (or drops below) a specific threshold.

In our example, that could mean when one of the funds dips below 20 per cent, or rises above 30 per cent of the portfolio’s overall asset allocation.

Don’t overdo it. There is no optimal frequency or threshold when selecting a rebalancing strategy. However, you can’t reasonably expect to keep your portfolio in exact alignment with your target asset allocation at all times. Rebalance your portfolio too often and your costs increase (commissions, taxes, time) without any of the corresponding benefits.

According to research by Vanguard, annual or semi-annual monitoring with rebalancing at 5 per cent thresholds is likely to produce a reasonable balance between controlling risk and minimizing costs for most investors.

Rebalance by adding new money

One other consideration is when you’re adding new money to your portfolio on a regular basis. For me, since I’m in the accumulation phase and investing regularly, I simply add new money to the fund that’s lagging behind its target asset allocation.

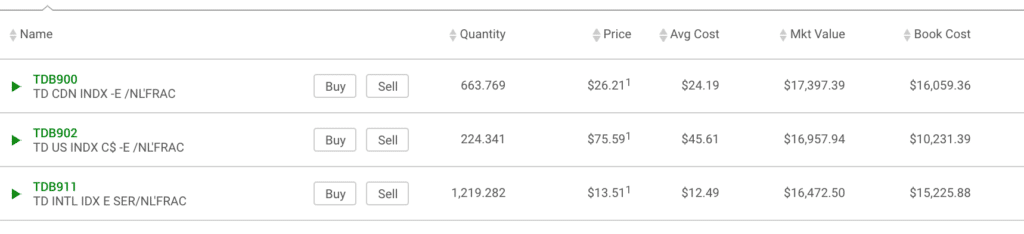

For instance, our kids’ RESP money is invested in three TD e-Series funds. Each month I contribute $416.66 into the RESP portfolio and then I need to decide how to allocate it – which fund gets the money?

My target asset mix is to have one-third in each of the Canadian, U.S., and International index funds. As you can see, I’ve done a really good job keeping this portfolio’s asset allocation in-line.

How? I always add new money to the fund that’s lagging behind in market value. So my next $416.66 contribution will likely go into the International index fund.

It’s interesting to note that the U.S. index fund has the lowest book value and least number of units held. I haven’t had to add much new money to this fund because the U.S. market has been on fire; increasing 65 per cent since I’ve held it, versus just 8 per cent each for the International and Canadian index funds.

One big household investment portfolio

Wouldn’t all this asset allocation business be easier if we only had one investment portfolio to manage? Unfortunately, many of us are dealing with multiple accounts, from RRSPs, to TFSAs, and even non-registered accounts. Some also have locked-in retirement accounts from previous jobs with investments that need to be managed.

The best advice with respect to asset allocation across multiple investment accounts is to treat your accounts as one big household portfolio. Continue Reading…