By Matt Montemurro, CFA, MBA, BMO ETFs

(Sponsor Content)

One of the biggest trends in the market, thus far in 2023, has been the flurry of inflows ($AUM) into money market and short-term fixed income. We have seen a “great migration to cash” as investors are literally being paid, handsomely, to park cash on the sidelines. We are now 6 months through the year and flows into the short end do not seem to be slowing down. Thus far YTD, we have seen $5.7bln flow into money market and ultra short-term fixed income ETFs, accounting for over 50% of all flows into fixed income ETFs in 2023 (Source: NBCFM ETF).

Money Market and Ultra Short-Term Fixed Income: after years of being a forgotten segment of the market, how and why are they the leading asset gatherer?

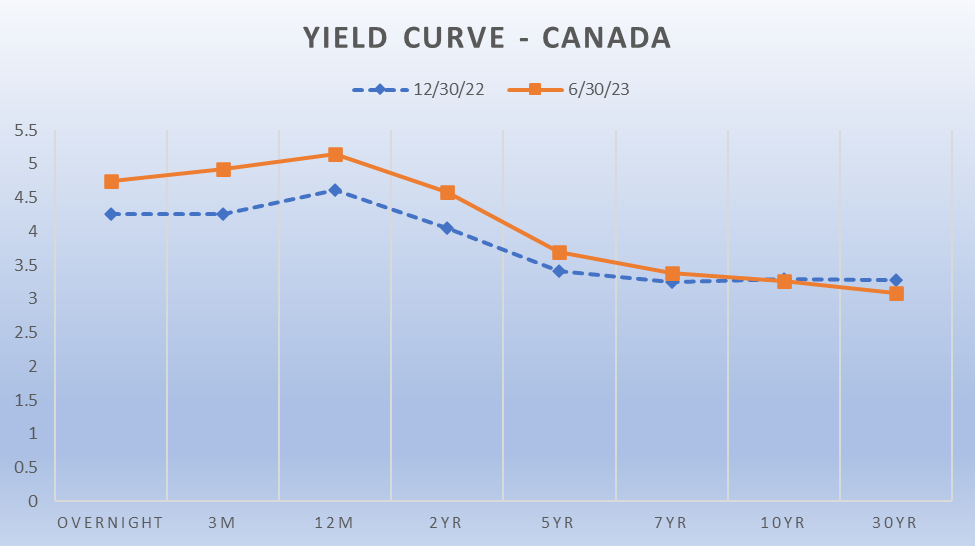

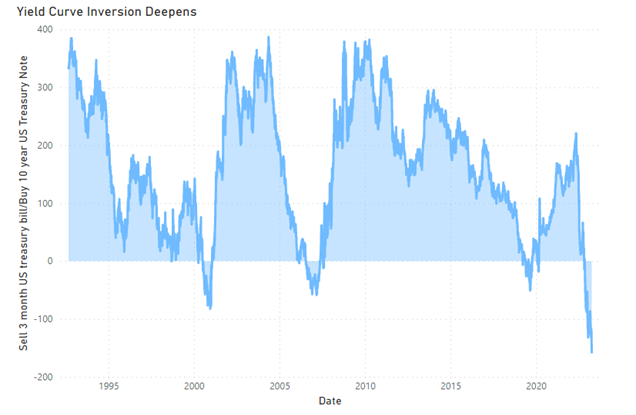

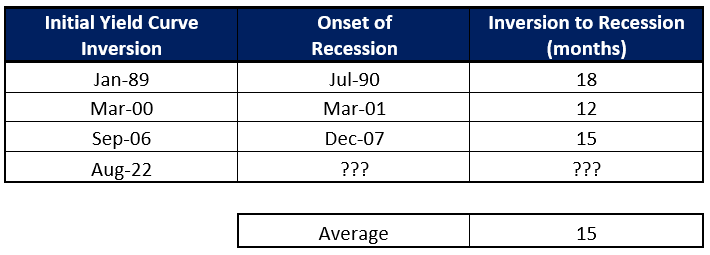

With the accelerated path of rising rates, we have seen in the short end of the yield curve; (the overnight rate) the yield curve inverted. An inversion of the yield curve is caused when shorter-term rates rise faster than longer-term rates. Generally, this is something that occurs but reverses quite quickly.

Not this time. We are currently in a period of a prolonged yield curve inversion, which could be a leading indicator of economic weakness to come. This inversion is exactly what these money market and ultra short-term fixed income investors are looking to cash in on. Lock in higher shorter-term rates and take advantage of the inverted yield curve.

For too long, investors were forced to move outside of investment grade bonds and further out the yield curve to achieve their yield and return expectations. The market has shifted that paradigm on its head and allowed investors to truly get paid to wait on the sidelines in cash.

Current Canadian Yield Curve

Source: Bloomberg, June 30, 2023

The short end appears to be the sweet spot for many investors, in terms of risk and reward.

Risk: by targeting the short end of the curve, investors will be minimizing their interest rate sensitivity (Duration exposure) and will generally be buying bonds that will be maturing in less than 1 year. Buying investment grade bonds, issued by high quality issuers, this close to maturity provides investors with downside protection as all these bonds will mature at par.[1]

Reward: Achieve a higher yield to maturity than further out the curve. Allowing investors to earn higher yields for lower interest rate sensitivity risk. The current market isn’t paying investors to lend money for longer periods. The front end provides an extremely attractive proposition for investors.

Today’s market is uniquely positioned and many market participants expect volatility to be on the horizon and as higher interest rates make their way through the economy, potentially causing growth to slowdown. Money market and short-term fixed income are well positioned for this environment, as investors can weather the potential volatility in the market while still meeting income and return needs. Continue Reading…