by Jeff Weniger, CFA, WisdomTree Investments

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

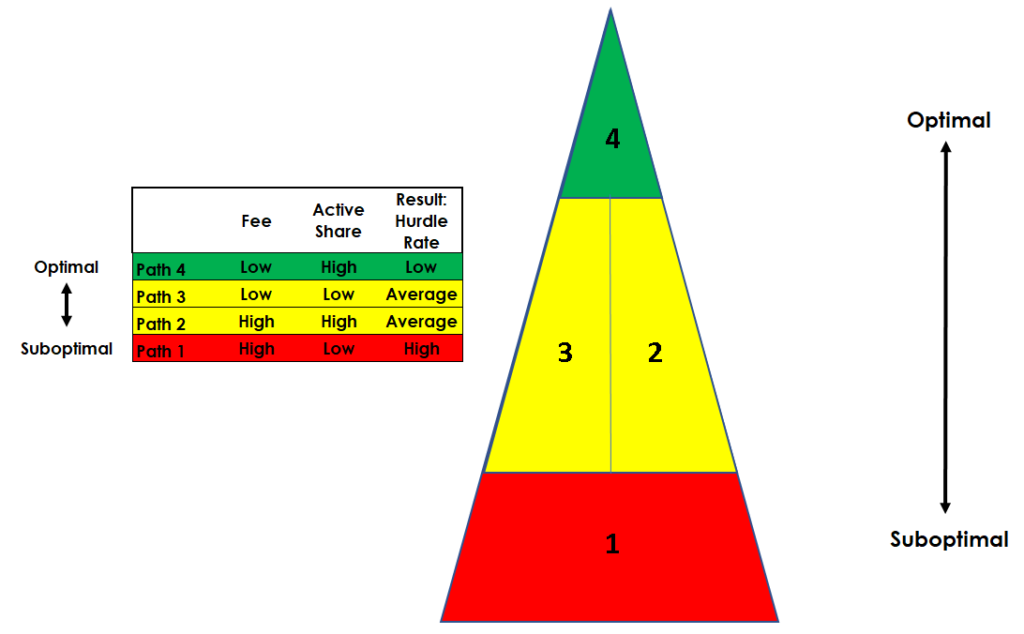

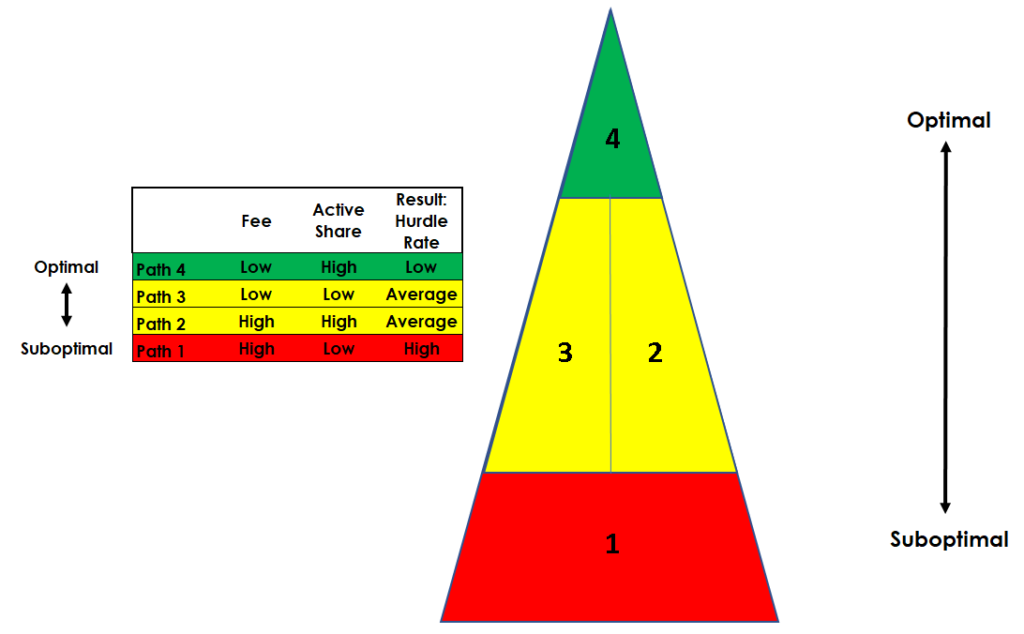

What is the profile of a fund that has the odds stacked against it?

For starters, “beta” index trackers that cover market capitalization-weighted indexes such as the S&P 500 may often lag their underlying index because of their fees, even though most of their expense ratios are tiny. Nevertheless, such funds may offer a better prospect than many active managers, who can’t get out of the way of their operating costs.

Another fund manager who is against the wall is the “closet indexer”: the career risk manager. These strategists claim to be coming up with great investments, but when you look under the hood, their holdings look just like their competitors’ funds. Then there is the manager who actually has a lot of unique holdings but high fees.

There is a fourth kind of manager who is not a market capitalization-weighted index strategist, a closet indexer or an expensive active manager. They have truly different holdings at digestible fees and higher active share.

To put this in context, a cap-weighted strategy would target an active share figure of 0% because it is trying to be exactly like the S&P 500, MSCI EAFE or some other major index. A closet indexing strategy may clock in at 30% or 40%. One that is totally different, with no holdings in common with its asset class, would have 100% active share.

Now, put active share in the context of fees: Using simple arithmetic, we can calculate the “hurdle rate” — popularized by Martijn Cremers at Notre Dame — which quantifies how well the active selections need to perform to cover their expense ratios. This really matters in picking a fund or ETF.

Path 1 is the worst. Sadly, trillions still sit in closet index funds that have low active share and high fees. Avoid these: Their existence is only justified if they somehow get past High hurdle rates.

Path 2 isn’t much better. These money managers at least have high active share, so they have the courage of their convictions, but they trip over their high fees. Their hurdle rates are Average.

Path 3 is a different breed, but just as bad as Path 2. These managers have low fees because they got the memo that the jig is up on huge expense ratios. But they are still closet indexing, hoping investors won’t notice their low active share. Their hurdle rates are Average.

Path 4 is hard to find. These are strategies that have both high active share and low fees. Their hurdle rates are Low: the sweet spot. Chances are good that a Path 4 fund is an ETF.

I put this in visual form in figure 1.

Figure 1: Visualizing the Four Paths

Find the Low Hurdle

Figure 2 puts numbers to this concept, with hypothetical Path 1, 2 and 3 managers.

Start with the Path 1 closet indexer. It has 35% active share, meaning the other 65% of its holdings are found in the cap-weighted benchmark. It charges 0.80%, so the unique holdings need to outperform by 229 basis points (bps) to match the market’s performance. That figure is found by dividing the expense ratio by the active share. It’s a big hurdle rate. Continue Reading…