By Justin Bender, CFA, CFP

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

If there were ever a contest held for “Canada’s Most Boring Investment Ever,” I’ll bet that bond ETFs and guaranteed investment certificates (or GICs) would duke it out in the final round. We buy one or the other, or maybe some of both, to offset our more glamorous (and more risky) stock funds with some sensible dependability. Then, thankless crowd that we are, we cringe at their related paltry returns.

So in the boring battle between them, which should you use? Laugh at the humble GIC if you must, but GICs may just help save the day in today’s fixed income markets.

Consider this. Between January 1st and April 30th, 2022, the 10-year Government of Canada benchmark bond yield has more than doubled, rising from 1.4% to 2.9%. As yields increased, bond prices dropped, causing Canadian broad-market bond ETFs to suffer double-digit losses so far this year, losing over 10% of their value.

Now, seasoned investors may be used to the gut-wrenching double-digit drops we periodically see in the stock markets, but some of you haven’t had to stomach seeing your supposedly “safe” bond ETF holdings show up in bright red when you login to your online accounts. If fixed income is going to be so boring, the least it can do is keep its head above water.

I don’t typically recommend switching up your holdings every time a market disappoints. But if your bond funds are giving you serious heartburn, GICs may be worth a second look.

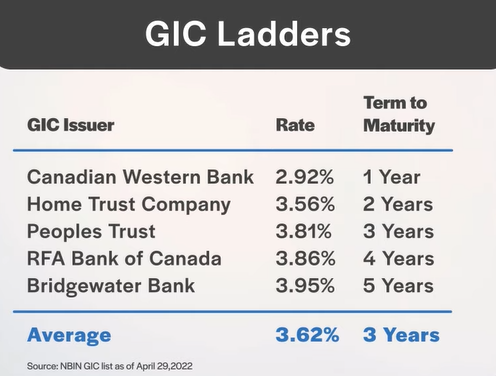

Let’s start off by talking about returns. Many GICs have yields that rival those of your favourite bond ETFs, but with a much lower average maturity. In fact, a 1–5 year GIC ladder currently boasts an average yield of 3.6%, with an average maturity of just 3 years. It’s called a “ladder” because you typically spread your GIC purchases evenly across 1-to-5-year maturities. This eliminates the need to predict future interest rate movements. So, if you have $100,000 to invest in GICs, you buy a $20,000 1-year GIC, a $20,000 2-year GIC, and so on, until you’ve built each “rung” in your 1-5 year ladder. As each GIC matures, you continue the ladder by reinvesting the proceeds into another GIC maturing in 5 years.

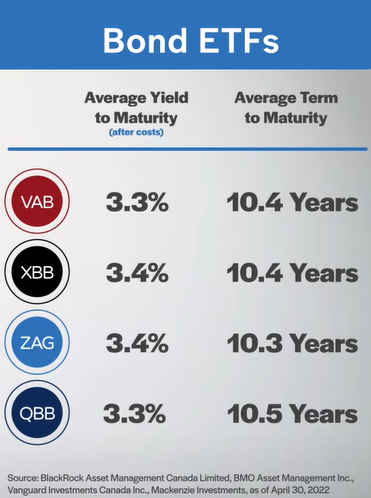

With a bond ETF, the best estimate we have of its future return is its weighted average yield-to-maturity. These days, in spring 2022, the yield-to-maturity on a broad-market Canadian bond ETF is about 3.4% after costs. And at 10.3 years, the weighted average maturity of the underlying bonds is significantly higher than a GIC ladder, exposing your investment to more interest rate risk.

With the GIC ladder, you can currently expect similar returns with far less term risk than what you’ll find in a bond ETF. In fact, since the end of 2011, a ladder of GICs has actually outperformed a broad-market Canadian bond ETF, with a much smoother ride along the way. It’s interesting to note that both options had the same 2.3% yield at the beginning of this measurement period.

Looking forward, there’s no guarantee that a ladder of GICs will always outperform a bond ETF over your specific investment timeframe, but there are still additional advantages of the strategy worth noting.

Advantages of GIC Ladders

GICs have shorter maturities. As mentioned earlier, the average maturity is 3 years for a typical 1–5 year GIC ladder (with an equal investment in each of the ladder’s “rungs” or years). In comparison, the average maturity is 10 years for a broad-market Canadian bond ETF, like the BMO Aggregate Bond Index ETF (ZAG). This makes the bond ETF more vulnerable to interest rate increases than a GIC ladder. If you’re concerned with the potential of further interest rate hikes down the road, a ladder of GICs may be more appropriate for your risk appetite. Keep in mind that if bond yields decrease from their current levels, bond ETFs could recover some of their losses (while your GIC ladder won’t experience the same price pop). Continue Reading…