It might seem counterintuitive to spend down your own retirement savings while at the same time deferring government benefits such as CPP and OAS past age 65. But that’s precisely the type of strategy that can increase your income, save on taxes, and protect against outliving your money.

Here are three reasons to take CPP at age 70:

1.) Enhanced CPP Benefit – Get up to 42 per cent more!

The standard age to take your CPP benefits is at 65, but you can take your retirement pension as early as 60 or as late as age 70. It might sound like a good idea to take CPP as soon as you’re eligible but you should know that by doing so you’ll forfeit 7.2 per cent each year you receive it before age 65.

Indeed, you’ll get up to 36 per cent less CPP if you take it immediately at age 60 rather than waiting until age 65. That alone should give you pause before deciding to take CPP early. What about taking it later?

There’s a strong incentive for deferring your CPP benefits past age 65. You’ll receive 8.4 per cent more each year that you delay taking CPP (up to a maximum of 42 per cent more if you take CPP at age 70). Note there is no incentive to delay taking CPP after age 70.

Let’s show a quick example. The maximum monthly CPP payment one could receive at age 65 (in 2019) is $1,154.58. Most people don’t receive the maximum, however, so we’ll use the average amount for new beneficiaries, which is $664.41 per month. Now let’s convert that to an annual amount for this example = $7,973.

Suppose our retiree decides to take her CPP benefits at the earliest possible time (age 60). That annual amount will get reduced by 36 per cent, from $7,973 to $5,862: a loss of $2,111 per year.

Now suppose she waits until age 70 to take her CPP benefits. Her annual benefits will increase by 42 per cent, giving her a total of $11,322. That’s an increase of $3,349 per year for her lifetime (indexed to inflation).

2.) Save on taxes from mandatory RRSP withdrawals and OAS clawbacks

Mandatory minimum withdrawal schedules are a big bone of contention for retirees when they convert their RRSP to an RRIF. For larger RRIFs, the mandatory withdrawals can trigger OAS clawbacks and give the retiree more income than he or she needs in a given year.

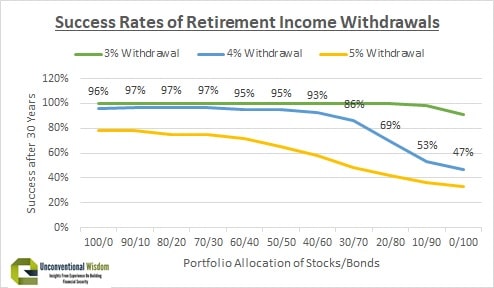

The gradual increase in the percentage withdrawn also does not jive with our belief in the 4 per cent rule, which will help our money last a lifetime.

You can withdraw from an RRSP at anytime, however, and doing so may come in handy for those who retire early (say between age 55-64). That’s because you can begin modest drawdowns of your retirement savings to augment a workplace pension or other savings to tide you over until age 65 or older.

Tax problems and OAS clawbacks occur when all of your retirement income streams collide simultaneously. But with a delayed CPP approach your RRSP will be much smaller by the time you’re forced to convert it to a RRIF and make minimum mandatory withdrawals. Continue Reading…