By Steve Lowrie, CFA

Special to the Financial Independence Hub

In my recent mid-year letter to clients, I decided we’d best just call a spade a spade, so I began as follows:

“Let’s not sugarcoat this: 2022 has challenged investors on nearly every financial front imaginable so far this year.”

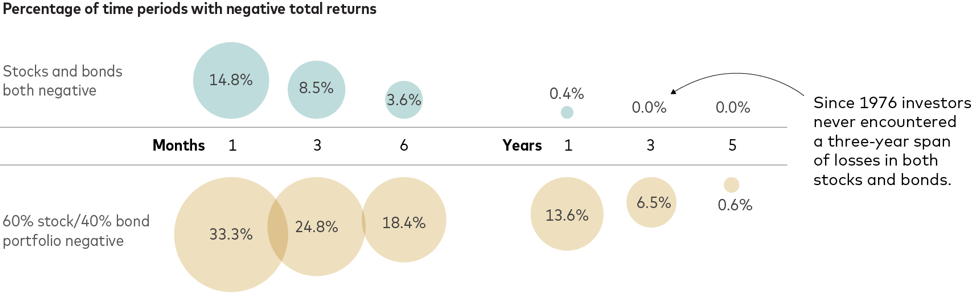

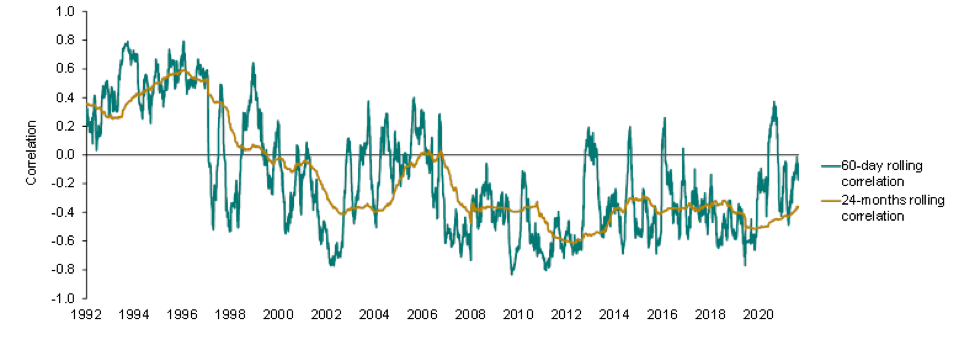

Stock and bond markets plummeting in tandem, the war in the Ukraine, rises in interest rates, threats of a looming recession … You’re probably already well aware of the volume of news wearing us down. As I wrote to my clients:

“the financial press has gone on a feeding frenzy in response, serving up heaping helpings of negativity upon negativity.”

Everyone loves a Perma-Bear

Whether by traditional channels or social media streams, amplifying extreme news is in large part what the popular financial press does.

They’re not entirely to blame; we consumers tend to gobble it up with a spoon. That’s thanks to a behavioural bias known as loss aversion, which causes the average investor to dislike losing money approximately twice as much as they enjoy gaining it. Our “fight or flight” instincts basically prime us remain on constant high-alert when it comes to protecting our life’s savings.

Media outlets know that, and routinely round up a stable of talking heads to scratch that behavioural itch. Their “regulars” even earn catchy nicknames:

Perma-bear

Back in 2012, economist David Rosenberg put together a presentation called 51 Signs the Economy Is a Total Disaster. (What, only 51?) We know that reality begged to differ. He tried again in 2019, when he declared: “We’re going into a recession … I think it will be this coming year.” It didn’t happen.

Dr. Doom

Whenever the press needs a fresh Armageddon forecast, they know they can call on “Dr. Doom” economist Nouriel Roubini. It doesn’t seem to matter that he’s been mostly wrong far more often than not. As recently as early July, Roubini was predicting a 50% freefall in the stock market. So far, not so much (thankfully).

Recession Man

As reported in ‘Recession Man’: Burry’s Tweets Resonate With Traders Worried About A Downturn, hedge fund manager Michael Burry built his fame from correctly calling the 2007 U.S. subprime mortgage crash. Lately, he’s been posting cryptic tweets to his nearly 1 million followers that “reflect increasing fears of an economic downturn.” As academic Peter Atwater explains of Burry’s popularity:

“The tweets that get shared and liked the most are the ones that fit with how we feel the most … Twitter is an enormous mirror.”

If you look closer, you might spot a card hiding up these soothsayers’ sleeves: with a large, random group of “experts” loudly predicting doom and gloom nearly all the time, basic statistics informs us: a few of them are going to be right every so often, with seemingly uncanny accuracy. Their fortuitous timing makes them look super smart, which earns them even more fame. The cycle continues.

Going on a Financial Media Diet

On many fronts, times are indeed disheartening, and we’re as worn out as you are by the weight of the world. That said, there are already way too many outlets cramming worst-case scenarios down our throats and crushing investment resolve. To offset a bitter pill overdose, following are a few more nutritious news sources to reinforce why we remain confident that capital markets will continue to prevail over time, and that long-term investors should just stick to their plan.

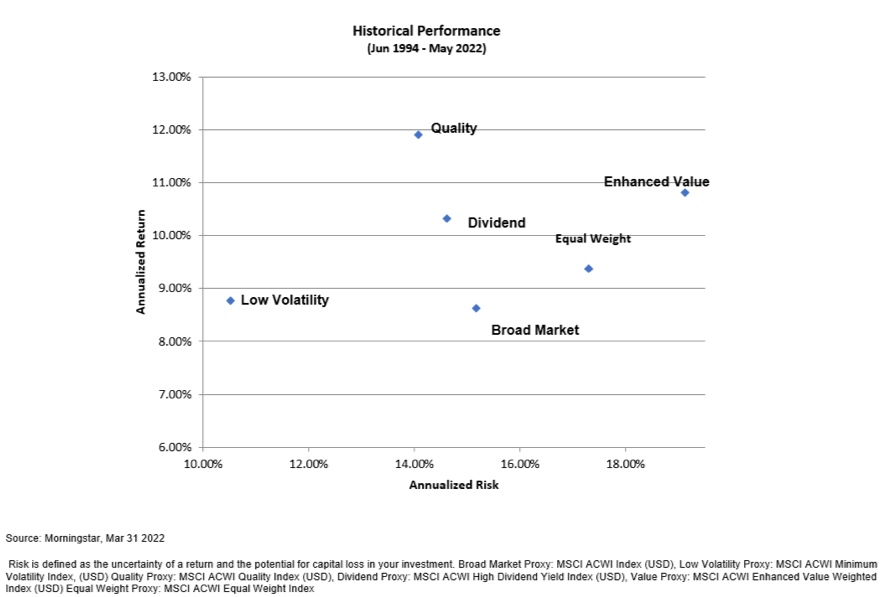

Stock Markets Grow

The following chart is one of our favorites, as it shows at a glance that which the bad news bears routinely disregard: Stock markets have gone up nicely, and far more frequently than they’ve gone down. We have no reason to believe current trends are going to alter this uplifting, nearly century-long reality.¹ Continue Reading…

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print