By Noah Solomon

Special to Financial Independence Hub

It goes without saying that 2022 was a less than stellar year for equity investors. The MSCI All Country World Index of stocks fell 18.4%. There was virtually nowhere to hide, with equities in nearly every country and region suffering significant losses. Canadian stocks were somewhat of a standout, with the TSX Composite Index falling only 5.8% for the year.

Looking below the surface, there was an interesting development underlying these broader market movements, with value stocks far outpacing their growth counterparts. Globally, value stocks suffered a loss of 7.5% as compared to a decline of 28.6% in growth stocks. This substantial outperformance was pervasive across countries and regions, including the U.S., Europe, Asia, and emerging markets. In the U.S., 2022’s outperformance of value stocks was the highest since the collapse of the tech bubble in 2000.

These historically outsized numbers have left investors wondering whether value’s outperformance has any legs left and/or whether they should now be tilting their portfolios in favor of a relative rebound in growth stocks. As the following missive demonstrates, value stocks are far more likely than not to continue outperforming.

Context is everything: Value is the “Dog” that finally has its Day

From a contextual perspective, 2022 followed an unprecedented period of value stock underperformance.

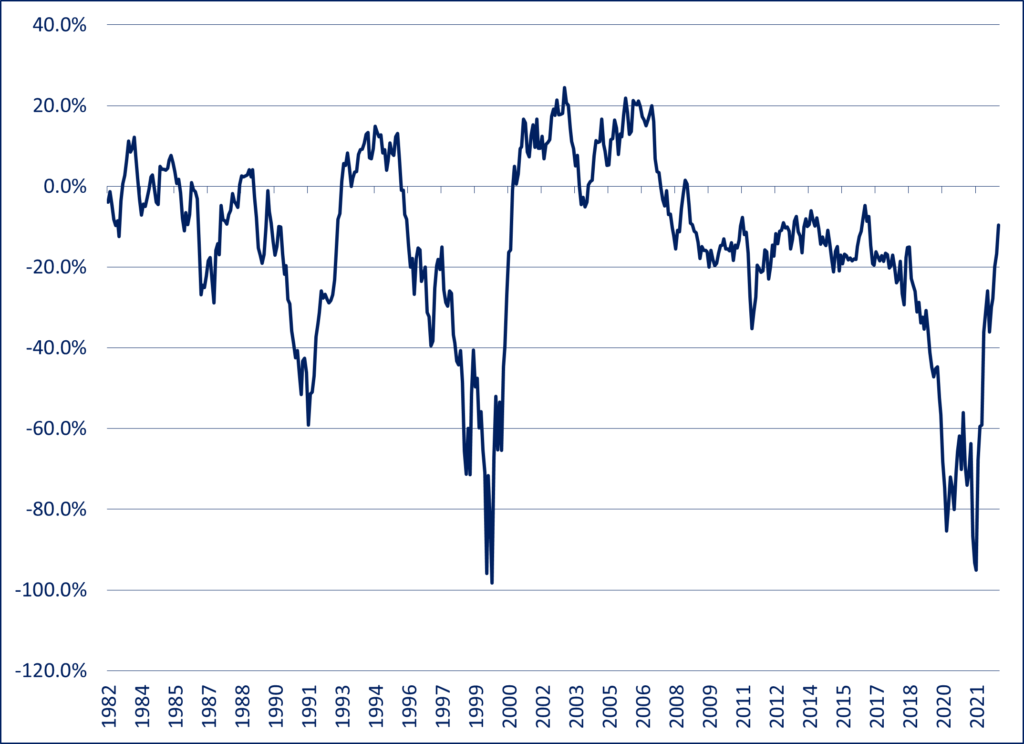

U.S Value vs. U.S. Growth Stocks – Rolling 3 Year Returns: 1982-2022

Although there have been (and will be) times when value stocks underperform their growth counterparts, the sheer scale of value’s underperformance in the several years preceding 2022 is almost without precedent in modern history. The extent of value vs. growth underperformance is matched only by that which occurred during growth stocks’ heyday in the internet bubble of the late 1990s.

Shades of Tech Bubble Insanity

The relative performance of growth vs. value stocks cannot be deemed either rational or irrational without analyzing their relative valuations. To the extent that the phenomenal winning streak of growth vs. value stocks in the runup to 2022 can be justified by commensurately superior earnings growth, it can be construed as rational. On the other hand, if the “rubber” of growth’s outperformance never met the “road” of superior profits, then at the very least you need to consider the possibility that crazy (i.e. greed, hope, etc.) had indeed entered the building.

The extreme valuations reached by many growth companies during the height of the pandemic bring to mind a warning that was issued by a market commentator during the tech bubble of the late 1990s, who stated that the prices of many stocks were “not only discounting the future, but also the hereafter.”

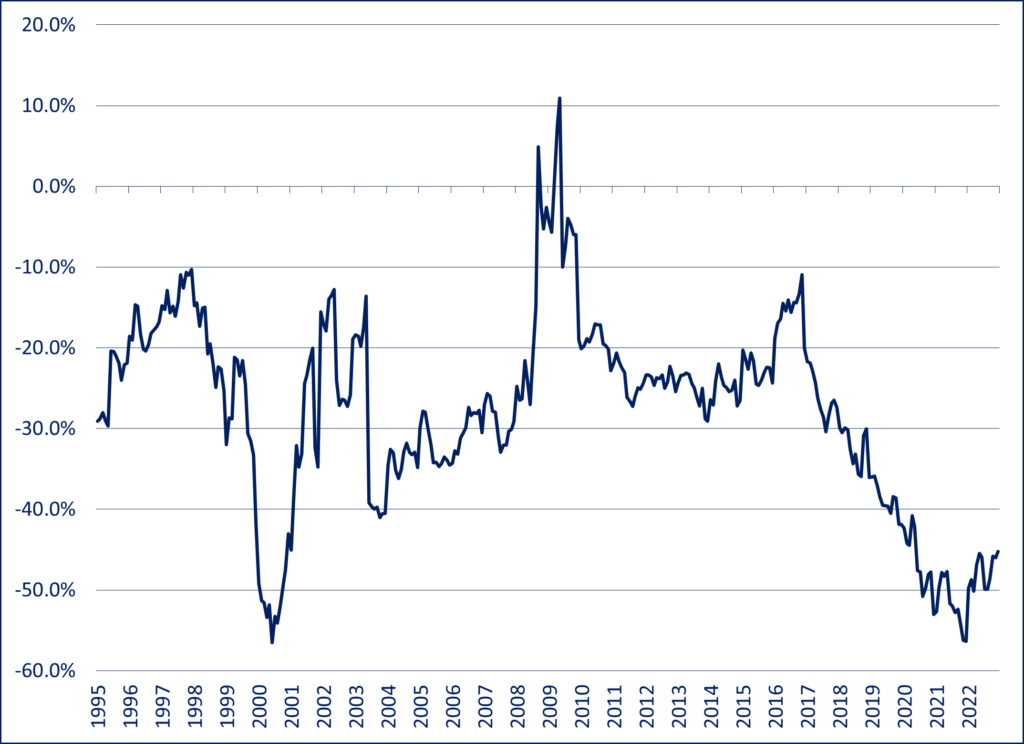

U.S. Value Stocks: Valuation Discount to U.S. Growth Stocks: (1995-2022)

Based on forward PE ratios, at the end of 2021 U.S. value stocks stood at a 56.3% discount to U.S. growth stocks. From a historical perspective, this discount is over double the average discount of 27.9% since 1995 and is matched only by the 56.6% discount near the height of the tech bubble in early 2000. This valuation anomaly was not just a U.S. phenomenon, with global value stocks hitting a 57.5% discount to global growth stocks, more than twice their average discount of 27.6% since 2002 and even larger than that which prevailed in early 2000 at the peak of the tech mania. Continue Reading…